Running a record label is a pain in the ass. It always begins with the best of intentions that reside somewhere in the mix of DIY ethics, wanting to support your friends, and simply trying to release your band’s arguably mediocre record when nobody else will do it.

Before you know it, you end up with maxed out credit cards, an archive of frustrated emails sent to vinyl pressing plant ten states away, a boyfriend or girlfriend who hates you, and your boxes of unsold 7-inches serve as makeshift coffee tables in your crappy apartment.

Best case scenario typically means that you don’t end up broke, some of your label’s releases get reviewed by niche publications, and most of your records actually found homes in other people’s collections. This is what punks call “success.”

Prior to the Internet and before the Mp3-ization of music, the prospects for walking down such a gilded path were certainly better for the aspiring record publisher, but it’s often been a losing bet, regardless of the decade. Thankfully, punks throughout the world have always thwarted such commonsense logistics and done it anyway.

Some of my favorite records (and yours, too, I imagine) would have never seen the light of day were it not for such beautiful thickheadedness and raw determination.

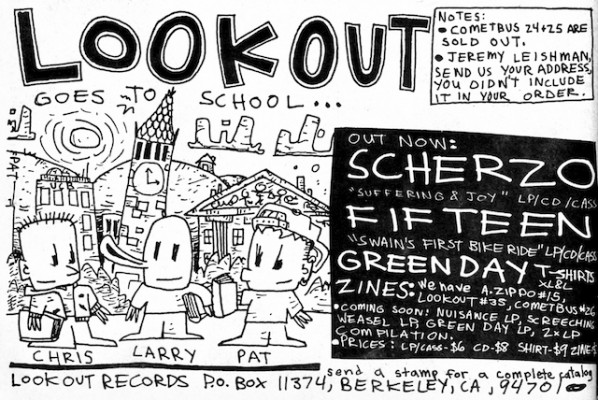

Part of the reason so many punks my age have gone broke at least once from putting out records is because there were so many labels doing it so well in the 1980s and 1990s. For most of its existence, Lookout Records was amongst the standouts in the US, having released a number of now-classic punk albums in addition to the first records from Green Day that brought the label both broader recognition and a surprising amount of financial success.

That is, until the walls came crashing down following the departure of the label’s founder and longtime proprietor, Larry Livermore, who I recently interviewed about his new book on the subject: How to Ru(i)n a Record Label: The Story of Lookout Records.

While I was expecting to simply talk music with Livermore, I was pleased to see our conversation naturally drift between the overlapping terrains of punk, politics, records, and places that seem to inform his persona in the same way they animate the stories in his book.

In this, the second part of the interview (CLICK HERE FOR PART ONE), Livermore begins by discussing what happened and where it all went wrong

Z: Did it take a long time for the label’s monetary problems to get sorted out? Are things finally resolved with the bands?

L: I would say certain things are still up in the air. One thing I’m very pleased I did was to write into all the contracts a provision that allowed the bands to regain ownership of their catalogue if they weren’t paid for a period longer than 6 months. Musicians being musicians, a lot of them let it go for many years. They said, “Oh, Lookout will probably pay us one of these days,” until they finally said, “Wait, wait, wait a second.” This was especially true with the bigger bands, where the money owed to them reached up into the hundreds of thousands.

So, they were able legally to own their own music again. Many, if not most, bands lost quite a bit of money. Well, I shouldn’t say ‘most’ because some never earned much to begin with – the more cult favorites who only sold a few thousand records – but the bigger bands did, in fact, lose hundreds of thousands of dollars. However, on the more positive side, they had the rights to just take their records and issue them on another label when they were ready. With bands like Green Day and Operation Ivy. they probably made more money in the long run because they released them on another label with just as good, or better, terms.

But the downside is that because some of the bands weren’t popular enough (or not organized, or business-minded enough), their records went into limbo or are more or less in the dead zone, which is very sad. It’s ironic, because if I had just been a little less reticent about earning more money, or doing conventional business practices, Lookout would’ve been on a sounder financial footing and maybe could’ve stayed intact. But, unfortunately, I don’t think it would have under the new management. So, ultimately, I still have to take responsibility for bailing out when I did.

It’s a mystery much talked about in the independent music industry, if there is such a thing: Where did all of Lookout’s money go? Nobody seriously knows. One really intrepid and skillful reporter from the East Bay Express did a story in 2005 where he interviewed all sorts of people and tried to figure it out. He had a few clues –that they had squandered a lot of money on high living and inefficient business practices – but that would’ve only accounted for the label’s share of the money…not all the bands’ share. So, it’s a mystery and though I’ve had conversations with Chris and Pat a number of times over the years, I still don’t know. Lookout was in very good shape at the time I left. In keeping with that same discomfort about money, I didn’t really take anything, beyond what I already earned, when I got out.

Z: You basically handed off Lookout Records and I was rather surprised that you didn’t have any sort of a grand buyout or that you didn’t formally sell the label to the folks who took the helm. But perhaps it makes sense, given that you also describe having increasing bouts of depression and drinking at that time – your previous book (Spy Rock Memories) candidly states that you were “flipping out.”

L: It was a little bit flipping out and it was also taking the easiest way out. It was irresponsible both to myself and to the bands and employees because I built this thing and brought all these people into it, and had more of a responsibility to them. If nothing else, it would’ve made sense to maintain a financial interest in the label so that when things started going wrong I could’ve come back and said, “Ok, let’s sort this out. You, you and you are fired…and you and you are gonna do this to get it back on track.” I’m not guaranteeing it would have worked but there’s a good possibility. That would have made sense to do.

The other alternative would’ve been to sell Lookout off to a larger label. And that’s where that ambivalence just really creeps in. In my book, I comment on the distinction between the very political, overly-scrupulous nature of the Bay Area punk scene vs. the southern California punk scene, where they had no problem admitting that they wanted to make some money.

I remember Brett from Epitaph Records calling me one day and casually mentioning, “I just sold the Offspring record to Columbia for $10 million.” He was not bragging – I mean he was obviously pleased – but it was not an issue to him. It was like, “Somebody says he wants to buy this contract for $10 million so, sure, why not! The Offspring wants to do it. I want to do it, so everything is great.” You couldn’t do that in the Bay Area without getting crucified.

Z: Lookout wasn’t known for having a roster of political bands, but you describe a number of different times and places in your past that were suffused with politics and music, though not always in conversation with each other. Even by themselves, you found things to be too authoritarian with the White Panthers and, somewhat differently, with MRR. Do music and politics mix well?

L: I probably haven’t formed a definitive opinion on this until you asked me but I’ve come to believe that politics and music kinda have to dance with each other at arms length, if that makes sense, because it’s very rare that an overtly political band is also good musically, or vice versa. There’s always these contradictions. You know, there’s a place for music and politics to interact but it’s probably more as the soundtrack for the revolution rather than as the manifesto.

Z: But I also remember reading older zine articles from you, in particular, that were aimed at recruiting punks out West for direct action protests against logging in the redwood forests (Redwood Summer). It was part of a (then) broader effort to harness some of the energy and ethics in the punk scene and direct it toward something other than making music.

L: Yeah. I tried to use zines and punk rock media technology to try to get people involved. What’s funny is that a lot of the people who came out there sort of turned into these punk-hippies and pot-smoking Dead heads. A lot of the Redwood Summer music was not that great [laughs].

And, again, here’s one of the places where I ran into big problems with Tim Yohannan, who was almost anti-environmental. I remember when I was living at the MRR house there was a point when I stayed away for several days covering the offshore oil hearings up on the north coast because to me it was like the environmental Woodstock – thousands of people showed up to protest against oil drilling. I got back and Tim was furious. I said, “but this is an important story…I’m gonna do it for MRR and for my own magazine.” And he’s like, “there’s nothing radical about that. It’s just a bunch of yuppies don’t want their ocean views spoiled!” [laughs]

That was one of the things we really started arguing about. I mean, he basically drove a car everywhere and smoked cigarettes constantly and loved eating greasy ribs from Styrofoam containers. You know, we were like, “you’re a walking environmental disaster.” [laughs]

Z: Do you see things happening in punk rock today that still excite you?

L: I was pretty excited for a few years about the whole New York, Baltimore, East Coast pop punk thing. In retrospect it was more of a nostalgia movement, I think, then a new development. It’s interesting. This is the first time in my life that I’m not caught up in a musical/cultural scene and it doesn’t bother me.

You know, I get asked all the time in interviews, “When is punk rock gonna come back?” Or, “What is the new happening punk rock thing?” But, to be honest, it’s sort of a retro movement now. There will always be punk rock and some of it will be quite good, but it’s basically older people re-enacting the stuff from their past. It’s kind of like the rockabilly conventions where everyone dresses up like it’s the ’50s. And I know some people who are into that, and they enjoy the hell out of it. But it’s probably not going to change the world; it’s just a fun thing for older people to do.

Z: I remember when I was younger people would joke that rockabilly is where punks go to retire.

L: Well that certainly makes sense. You know, if you don’t lose your hair you become rockabilly and, if you do, you become a skinhead (laughs). I remember hanging out in London about twety some years ago and meeting some guys who were basically 35-40 yr old Teddy Boys (laughs), which is of course form an English movement in the fifties, and they still had the greaser haircuts and the whole style. I remember thinking about England at the time as having hese archeological or fossil layers of every subculture that was ever there – with little cults of them that were still visible.

Maybe it’s always been here, but I’m beginning to see that more in America, too. In some ways the punk scene is bigger than ever, but at the same time it is more or less replicating things that have been done and the age of the participants is steadily creeping up. I mean, there are teenage punks, but not a lot of them. When we started Gilman, the average age of the audience was not much more than mid-teens…late-teens at most.

Z: That’s actually one of the things that struck me most with the book’s photos – a lot of the folks in those bands, and at the core of the Gilman scene, were really young.

L: And everyone who sees those pictures remarks on that. “Oh my god, we were just babies.” [laughs]. But, yeah, that’s what was inspiring about it. If I look back to the White Panther days in Ann Arbor it was the same thing – the people who were writing manifestos and organizing weapons training were in their twenties and thirties, but the cadre, as they were called, were not much more than children.

Z: In thinking about all these convergences here and in your writing, one of the things I like about your work is your attention to space and place. It seems to really inform the way you organize and tell stories about your life experiences. But I also think it reflects just how much space and place shape, and are shaped by, different kinds of cultural formations or clusters of creativity, if you want to put it that way.

L: I’m very pleased that you noticed it. It’s something that, to an extent, just developed. If were teaching a writing class (which, I hasten to assure you, nobody has ever asked me to do), a sense of place would be one of the first elements.

My friend, Aaron Cometbus, has also written a great deal about some similar topics and we co-edit each other’s stuff. He and I often talk about how vital a sense of place is and about the importance of those details in writing. He loves to rave about some novel that was otherwise successful but was set in Berkeley – in some real places – and the author gets the name of a certain café just a letter or two wrong while maintaining that this was the center of his or her existence. To him and to me, something like that undermines the entire narrative. It’s like, “You weren’t really there. Come on.” [laughs]

Are you familiar with the Oscar Wilde essay, “The Decay of Lying”? It’s an essay where he laments that people are losing the ability to make up good stories. He’s basically talking about writing fiction, and he says that you have to recreate an exquisite and perfect and, in totally authentic detail, a world that never existed. And if you don’t succeed in that, nobody will believe you.

That might sound strange, but I feel like it’s even more important in nonfiction – that you really need to get the details right and, if you do, the setting can become a character or actor itself. A sense of place is really important to me but, for instance, I rarely spend a lot of time describing someone’s features or what they were wearing. The reader can often do a better job of filling that in than me.

Z: And you certainly could’ve spent a lot more time on various details associated with specific recordings, musicians, albums, and so on. But both with this book and Spy Rock Memories, the emphasis on time and place helps to explain, and give some context, to not just the label but also what it meant to be in and around that particular punk scene. I don’t think that could’ve translated if you were too hung up on the bands and who did what, when they did it, etc.

L: Well there is a certain audience, probably a significant audience, who would find all that fascinating. But I would probably bore myself to death trying to write about it.

Z: The last thing I wanted to ask before I let you go is about is the “smart punks club” you mentioned in your book. [laughs]

L: [laughs] Well, hopefully you can start a chapter at your college. Mine failed abysmally. It was totally tongue in cheek but it was also very serious because I was sick of, you know, people thinking you had to be really dumb to be punk. In fact, there were quite a few kids at Berkeley at that time who were also part of Gilman. It was my way of saying, “Come to Gilman, have fun, be in bands and stuff, but also do your homework….be on the honor roll….be smart.” [laughs]. Because America needs smart people – we’ve already got enough dumb ones.