One of the most persistent domestic critiques of Donald Trump is that his proposals are not truly American. From the White House to the protests at his rallies, he has been savaged for promoting the sort of extremism the United States has long ascribed to its enemies, thereby calling into question the self-righteous presumptions that undergird the nation’s foreign policy.

It is understandable that Trump’s detractors would want to feel this way. He is a source of embarrassment to almost everyone who has to represent the interests of the United States abroad, repeatedly stating out loud the sort of things that more practiced politicians would never share.

That helps to explain why otherwise measured commentators have felt comfortable invoking the term “fascism” when discussing his brand of blustery populism. It’s still a concept most Americans associate with Europe, after all.

But this perspective on Trump is not shared by actually existing Europeans. On the contrary, even those inclined to agree with much of his “strong man” posturing still think of him as quintessentially American.

Indeed, decades before he decided to enter the political arena, his brand was already identified with an impression of the United States that Europeans have been cultivating since the days of Charles Dickens: boorish, materialistic and proudly ignorant of a great deal, including the scorn of less immature nations.

To the extent that Trump seems to embody these qualities — in sharp contrast to the nation’s current President, who goes out of his way to disavow them — he has enabled Europeans who are beset by disturbing political and economic trends to displace their anxieties onto his candidacy. He can stand in for threats that have emerged closer to home, while still retaining enough otherness to make them feel better about themselves.

After all, like reality television, the volatile combination of xenophobia, resistance to centralized authority and pandering to white working-class voters started sweeping Europe well before Trump started running for President.

Some who believe The Donald is a lot savvier than he seems suspect his campaign of borrowing self-consciously from the playbook of reactionary European populism. But even if he stumbled into his remarkably successful attempt to position himself an outsider on the side of the People by accident, there’s no denying that his stance overlaps significantly with the movement that is threatening to render the high-handed bureaucracy in Brussels irrelevant.

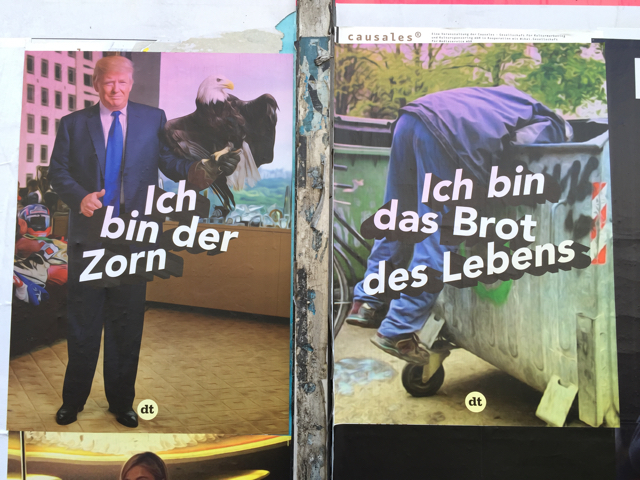

Thus, while the political posters from Berlin featured in this piece may be the product of a well-intentioned progressive impulse, it is deeply problematic that their creators chose Trump as their symbol for rage and, given the montage effect created by the right panel, a concomitant heartlessness. To be sure, he does a great job of representing those qualities. But there are plenty of European politicians who do as well, ones who, because they are not so easily dismissed as foreign, would better communicate the message that the continent’s haves are waging what Antonio Gramsci called a “war of position” against its have-nots.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit