Significant misunderstanding has developed concerning US policy towards Indochina in the decade of World War II and its aftermath. A number of historians have held that anti-colonialism governed US policy and actions up until 1950, when containment of communism supervened.

For example, Bernard Fall (e.g. in his 1967 postmortem book, Last Reflections on a War) categorized American policy toward Indochina in six periods:

“(1) Anti-Vichy, 1940-1945; (2) Pro-Viet Minh, 1945-1946; (3) Non-involvement, 1946-June 1950; (4) Pro-French, 1950-July 1954; (5) Non-military involvement, 1954-November 1961; (6) Direct and full involvement, 1961-.” Commenting that the first four periods are those “least known even to the specialist,” Fall developed the thesis that President Roosevelt was determined “to eliminate the French from Indochina at all costs,” and had pressured the Allies to establish an international trusteeship to administer Indochina until the nations there were ready to assume full independence.

This obdurate anti-colonialism, in Fall’s view, led to cold refusal of American aid for French resistance fighters, and to a policy of promoting Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh as the alternative to restoring the French bonds.

But, the argument goes, Roosevelt died, and principle faded; by late 1946, anti-colonialism mutated into neutrality. According to Fall: “Whether this was due to a deliberate policy in Washington or, conversely, to an absence of policy, is not quite clear. . . . The United States, preoccupied in Europe, ceased to be a diplomatic factor in Indochina until the outbreak of the Korean War.” In 1950, anti-communism asserted itself, and in a remarkable volte-face, the United States threw its economic and military resources behind France in its war against the Viet Minh.

Other commentators, conversely – prominent among them, the historians of the Viet Minh – have described US policy as consistently condoning and assisting the reimposition of French colonial power in Indochina, with a concomitant disregard for the nationalist aspirations of the Vietnamese. Neither interpretation squares with the record; the United States was less concerned over Indochina, and less purposeful than either assumes. Ambivalence characterized US policy during World War II, and was the root of much subsequent misunderstanding.

On the one hand, the US repeatedly reassured the French that its colonial possessions would be returned to it after the war. On the other hand, the US broadly committed itself in the Atlantic Charter to support national self-determination, and President Roosevelt personally and vehemently advocated independence for Indochina. F.D.R. regarded Indochina as a flagrant example of onerous colonialism which should be turned over to a trusteeship rather than returned to France. […]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BzXkj1R7GF0

The President’s trusteeship concept foundered as early as March 1943, when the US discovered that the British, concerned over possible prejudice to Commonwealth policy, proved to be unwilling to join in any declaration on trusteeships, and indeed any statement endorsing national independence which went beyond the Atlantic Charter’s vague “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.” […]

At each key decisional point at which the President could have influenced the course of events toward trusteeship, in relations with the UK, in casting the United Nations Charter, in instructions to allied commanders, he declined to do so; hence, despite his lip service to trusteeship and anti-colonialism, F.D.R. in fact assigned to Indochina a status correlative to Burma, Malaya, Singapore and Indonesia: free territory to be reconquered and returned to its former owners. Non-intervention by the US on behalf of the Vietnamese was tantamount to acceptance of the French return. […]

With British cooperation, French military forces were reestablished in South Vietnam in September, 1945. The US expressed dismay at the outbreak of guerrilla warfare which followed, and pointed out that while it had no intention of opposing the reestablishment of French control, “it is not the policy of this government to assist the French to reestablish their control over Indochina by force, and the willingness of the US to see French control reestablished assumes that [the] French claim to have the support of the population in Indochina is borne out by future events.”

Through the fall and winter of 1945-1946, the US received a series of requests from Ho Chi Minh for intervention in Vietnam; these were, on the record, unanswered. However, the US steadfastly refused to assist the French military effort, e.g., forbidding American flag vessels to carry troops or war materiel to Vietnam. On March 6, 1946, the French and Ho signed an Accord in which Ho acceded to French reentry into North Vietnam in return for recognition of the DRV as a “Free State,” part of the French Union.

As of April 1946, allied occupation of Indochina was officially terminated, and the US acknowledged to France that all of Indochina had reverted to French control. Thereafter, the problems of US policy toward Vietnam were dealt with in the context of the US relationship with France. […]

Origins of US Involvement in Vietnam

The collapse of the Chinese Nationalist government in 1949 sharpened American apprehensions over communist expansion in the Far East, and hastened US measures to counter the threat posed by Mao’s China. The US sought to create and employ policy instruments similar to those it was bringing into play against the Soviets in Europe: collective security organizations, economic aid, and military assistance. […]

The US decided that the impetus for collective security in Asia should come from the Asians, but by late 1949, it also recognized that action was necessary in Indochina. Thus, in the closing months of 1949, the course of US policy was set to block further communist expansion in Asia: by collective security if the Asians were forthcoming; by collaboration with major European allies and commonwealth nations, if possible; but bilaterally if necessary. On that policy course lay the Korean War, the forming of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization of 1954, and the progressively deepening US involvement in Vietnam.

January and February, 1950, were pivotal months. The French took the first concrete steps toward transferring public administration to Bao Dai’s State of Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh denied the legitimacy of the latter, proclaiming the Democratic Republic of Vientam as the “only legal government of the Vietnam people,” and was formally recognized by Peking and Moscow. On 29 January 1950, the French Nation, Assembly approved legislation granting autonomy to the State of Vietnam. On February 1, 1950, Secretary of State Acheson made the following public statement:

The recognition by the Kremlin of Ho Chi Minh’s communist movement in Indochina comes as a surprise. The Soviet acknowledgment of this movement should remove any illusions as to the “nationalist” nature of Ho Chi Minh’s aims and reveals Ho in his true colors as the mortal enemy of native independence in Indochina.

Although timed in an effort to cloud the transfer of sovereignty France to the legal Governments of Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam, we have every reason to believe that those legal governments will proceed in their development toward stable governments representing the true nationalist sentiments of more than 20 million peoples of Indochina.

French action in transferring sovereignty to Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia has been in process for some time. Following French ratification, which is expected within a few days, the way will be open for recognition of these local governments by the countries of the world whose policies support the development of genuine national independence in former colonial areas. . . .

Formal French ratification of Vietnamese independence was announced 4 February 1950; on the same date, President Truman approved US recognition for Bao Dai. French requests for aid in Indochina followed within a few weeks. On May 8, 1950, the Secretary of State announced that:

The United States Government convinced that neither national independence nor democratic evolution exist in any area dominated by Soviet imperialism, considers the situation to be such as to warrant its according economic aid and military equipment to the Associated State of Indochina and to France in order to assist them in restoring stability and permitting these states to pursue their peaceful and democratic development.

The US thereafter was deeply involved in the developing war. But it cannot be said that the extension of aid was a volte-face of US policy precipitated solely by the events of 1950. It appears rather as the denouement of a cohesive progression of US policy decisions stemming from the 1945 determination that France should decide the political future of Vietnamese nationalism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=04OKzVXtW7o

Neither the modest O.S.S. aid to the Viet Minh in 1945, nor the US refusal to abet French recourse to arms the same year, signalled US backing of Ho Chi Minh. To the contrary, the US was very wary of Ho, apprehensive lest Paris’ imperialism be succeeded by control from Moscow. Uncertainty characterized the US attitude toward Ho through 1948, but the US incessantly pressured France to accommodate “genuine” Vietnamese nationalism and independence.

In early 1950, both the apparent fruition of the Bao Dai solution, and the patent alignment of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam with the USSR and Communist China, impelled the US to more direct intervention in Vietnam.

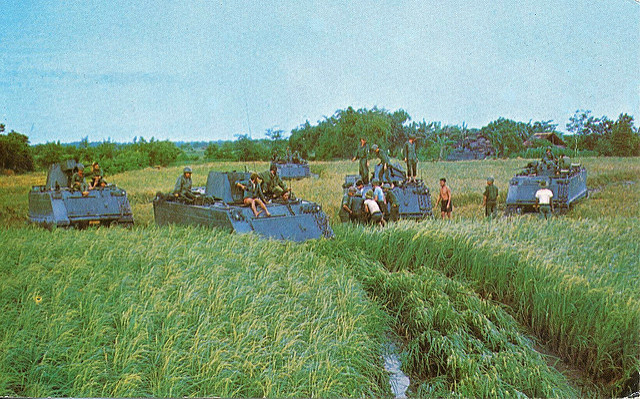

Excerpt from The Pentagon Papers (Part 1). Photograph courtesy of MaxHai. Published under a Creative Commons License.