If you have a lot of friends who teach university courses, as I do, your social media feed at this time of year is probably filled with complaints. Instructors keep being asked to do more for less pay. The higher-ups who shape their conditions of employment treat them with blatant disrespect. Most of their students show little interest in working hard. And they’re getting worse, too.

That’s the picture that comes through on Facebook and Twitter, anyway. I nod my head in agreement. But I try not to add to the chorus. It’s important to keep things in perspective, I tell myself. Yes, life is generally getting worse for university instructors. Yet it’s also getting worse for the majority of white-collar workers, not to mention what’s left of the working class. No matter how good it might feel to complain, it wouldn’t look that way to those people who have never achieved the small measure of dignity that comes from presiding over a class, who have never had the opportunity to do work that excites them intellectually, who frequently work harder for lower hourly wages.

Plus, it’s important to place the urge to complain in context. The end of the academic year is invariably the worst time for instructors. Nobody enjoys marking papers and exams. They are all tired and ready for a break. Ask them how they feel about their jobs in the fall and you will surely come away with a more positive perception of the “life of the mind.” The relentless budget cutting and micromanagement that have been eating away at universities since neoliberal policies were first implemented will still be there, making instructors’ lives more difficult than they need to be, but their passion for teaching will be revived.

Part of the reason for this is that they will once again be focused on the potential their students show rather than evidence of all the ways in which they have fallen short of achieving it. While the perception that performance keeps trending downward is widespread, most teachers still believe that this is a reflection of a deeply flawed education system rather than a decline in young people’s native abilities. It may be the height of hubris for them to imagine that they can be the ones to make progress where their predecessors have not, but this delusion is what motivates them to do better work in the classroom.

These are the points I go over in my head whenever I am tempted to complain. This time of year may be unpleasant, but it won’t always be this way. And the students who are frustrating me right now will give way to others who may help restore my faith in the profession I decided to pursue. I’m sure most of my colleagues go through a similar thought process, whether they choose to complain or not. It may be getting harder to sustain, as the line between universities and the “real world” becomes increasingly difficult to discern, but remains one of the ideological lubricants that keep the machinery of academia running.

This is where things get complicated. While it is usually in the best interest of anyone employed by universities to help steer them clear of trouble in the near future, trying to preserve some semblance of the status quo could well lead to a greater cataclysm down the road. So long as exhaustion and disillusionment gradually give way over the summer to renewed enthusiasm and willing self-delusion, it will be difficult to take the structural crisis in academia seriously.

I find this particularly alarming where the perceived decline in students’ performance is concerned. Again and again, I see friends on social media posting the most egregious examples of unpreparedness, whether they concern ignorance of historical context, basic rules of grammar or the behavioural codes that used to govern student-faculty interaction. Even when shared in a moment of extreme frustration, these examples tend to elicit a kind of laughter in solidarity. How can a third-year American university student have no idea when the nation’s Civil War was fought or what it was fought about? Is it really asking too much of undergraduates to expect them to make the proper distinction between “its” and “it’s”? Who could possibly think it’s a good idea to call up one’s professor at 2am and leave the message, “Bro, I need an extension”?

Believe me, I laugh along when I read tales like these. But I can’t escape a nagging sense that the real problem isn’t how students are being instructed in the classroom growing up, so much as what they are being taught to care about outside of educational institutions. It’s perfectly obvious to any young person who pays even partial attention to what has been going on in the world during their lifetime that securing a college degree right now is less about passing through a gateway to success than trying to limit the number of doors that will be barred from the get-go.

Higher education is rapidly becoming the equivalent of applying sun screen, a preventive measure that could, in theory, protect you from harm, but will produce negligible positive effects. And with new categories of employment being eliminated or severely reduced each year, that potential benefit threatens to be short-lived as well. Indeed, the pace of technological and social change is so great that the only thing time at a university can be expected to provide over the long-term is the experience of spending time at a university with one’s fellow students.

What matters most to students, then, is probably not anything specific they learn in the classroom — or, increasingly, its online equivalent — but the lessons they learn about finding a way to turn institutionally constrained social interactions to their advantage. No doubt this has always been the case, to a degree. But the difference today is that the value of higher education as a content-delivery mechanism is in steep decline even as the costs associated with it have been far outpacing inflation for decades. Unless students find a way to derive benefits from the time they spend in a university setting that exceed the bounds of traditional education, they will very likely perceive much of that experience as wasteful.

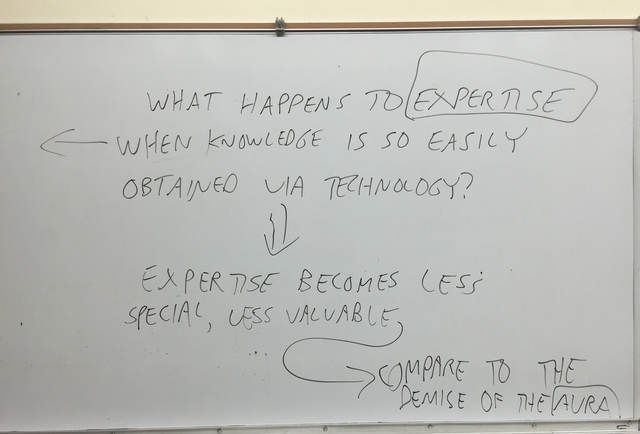

While the biggest reason for this is the increasing disconnect between academic achievement and future employment, it is also the case that students now have the resources to teach themselves how to do things as never before. From their perspective, the knowledge that their instructors spent decades amassing is no longer as valuable a commodity as it once was. Indeed, its rudiments have already been made available to them through technological means that are both inexpensive and constantly being improved through the collective action of a vast community of learners around the globe. And there are plenty of people out there, often without any kind of institutional sanction, who are more than happy to provide further instruction in their areas of expertise, sometimes for free and sometimes through alternative classes that function along the lines of the master-disciple relationship in certain religious traditions rather than the massively bureaucratized educational structures that define mainstream higher education.

Faced with this threat to their “market share”, it makes perfect sense that universities have been trying so hard to transform themselves along the lines of entities in the service sector not burdened by tradition. The consultants who have prodded them to downsize and outsource the work of actually educating students in favor of greater investment in their brand as an experience conceived more like a very long and expensive package tour — “Spend four years becoming the person you’ve always wanted to be!” — may seem hopelessly benighted to someone who still inhabits the academic ideology described above, but that doesn’t meant that their analysis of the economic landscape is wrong.

When instructors complain about their students’ performance, then, what they are really complaining about is those students’ failure to invest much energy in performing for them, as opposed to a wider university community in which what matters most is maximizing connections that might pay off in both short-term pleasure and long-term professional dividends. Unless instructors are willing and able to transmute the authority they still possess within the classroom into the sort of mentorship with meaningful staying power, their marginalization will only increase.

This is much easier said than done, of course. The entire structure of the modern university is set up to prevent that kind of direct teacher-student relationship in favor of one mediated by the institution, with its power to confer or deny the legitimacy of pedagogy. And much of the work done in recent decades to limit the potential for sexual harassment and other forms of impropriety, though a crucial way of redressing wrongs that have long plagued higher education, has also had the inadvertent effect of strengthening the position of administrators against the instructors they employ, particularly in contexts where mentorship must take place outside of a classroom setting.

What, then, is to be done? Would it be better for instructors to keep complaining at the start of the new academic year instead of reverting back to business as usual? Or is the precarity of their institutional situation now so great that their complaints would simply be brushed aside or, worse, regarded as a reason for dismissal, lest they sully the university’s brand? One possibility that is drawing a lot of interest, as it also did — mostly for different reasons — in the wake of the 1960s, is the creation of alternative educational structures that would be more flexible and empowering for instructors and students alike, permitting and even encouraging the sort of pedagogic continuity that the modern university discourages.

As promising as this approach might seem, though, the problem of legitimacy remains. Once a school takes the steps necessary to become the sort of institution stable enough to secure and sustain accreditation, it loses the incentive to prioritize the relationship between teacher and student. On the contrary, it is often in the school’s interest to intervene in that relationship as much as possible. Because once teachers no longer need the backing of a school in order to pursue their vocation, institutionalized pedagogy ceases to hold much appeal.

This antagonism is analogous to one that is also developing in the practice of medicine, where a series of behind-the-scenes arrangements between provider networks, insurers and government are what prevent physicians from maintaining the sort of relationship with their patients that used to lie at the heart of their craft. Many have been so discouraged by the bureaucracy that plagues their attempts to be good doctors that they are either limiting their hours or leaving the profession entirely.

The same situation has long been a problem in elementary and secondary education, where lack of autonomy is not offset by the financial rewards that physicians can at least look forward to. Faculty turnover at those levels is extremely high for that reason. And now that universities are exhibiting the same tendency to prioritize administrative control over other concerns, instructors there are also starting to leave in large numbers. Perhaps that is a necessary byproduct of the consolidation that was bound to come, however belatedly, to the business of higher education. But it would be nice to imagine a future in which instructors do not leave the classroom because they are underpaid, overmanaged and increasingly irrelevant.

Photograph courtesy of the author