In parliament the nation made its general will the law; that is, it made the law of the ruling class its general will. It renounces all will of its own before executive power and submits itself to the superior command of an alien, of authority. Executive power, in contrast to the legislative sort, expresses the heteronomy of a nation in contrast to its autonomy. France therefore seems to have escaped the despotism of a class only to fall back under the despotism of an individual, and what is more, under the authority of an individual without authority. The struggle seems to be settled in such a way that all classes, equally powerless and equally mute, fall on their knees before the rifle butt.

But the Revolution is thoroughgoing. It is still traveling through purgatory. It does its work methodically. By December 2, 1851, it had completed half of its preparatory work; now it is completing the other half. It first brought parliamentary power to completion, in order to be able to overthrow it. Now that the Revolution has achieved this, it is doing the same with executive power, reducing it to its purest expression, isolating it, setting itself up against itself as the sole target, in order to concentrate all its forces of destruction against it. And when it has accomplished this second half of its preliminary work, Europe will leap from its seat and exult: Well burrowed, old mole!

Executive power with its enormous bureaucratic and military organization, with its wide-ranging and ingenious state machinery, with a host of officials numbering half a million, besides an army of another half million – this terrifying parasitic body which enmeshes the body of French society and chokes all its pores sprang up in the time of the absolute monarchy, with the decay of the feudal system which it had helped to hasten. The seignorial privileges of the landowners and towns became transformed into so many attributes of state power, the feudal dignitaries into paid officials, and the motley patterns of conflicting medieval plenary powers into the regulated plan of a state authority whose work is divided and centralized as in a factory.

The first French Revolution, with its task of breaking all separate local, territorial, urban, and provincial powers in order to create the civil unity of the nation, was bound to develop what the monarchy had begun, centralization, but also, at the same time, the limits, the attributes, and the agents of governmental power. Napoleon completed this state machinery. The Legitimate Monarchy and the July Monarchy added nothing to it but a greater division of labor, increasing at the same rate as the division of labor inside the bourgeois society created new groups of interests, and therefore new material for the state administration.

Every common interest was immediately severed from society, countered by a higher, general interest, snatched from the activities of society’s members themselves and made an object of government activity – from a bridge, a schoolhouse, and the communal property of a village community, to the railroads, the national wealth, and the national university. Finally, the parliamentary republic, in its struggle against the Revolution, found itself compelled to strengthen the means and the centralization of governmental power with repressive measures. All revolutions perfected this machine instead of breaking it. The parties, which alternately contended for domination, regarded the possession of this huge state structure as the chief spoils of the victor.

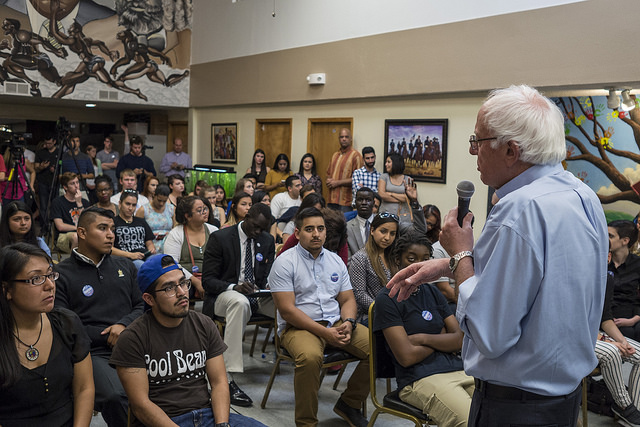

Excerpted from The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1897), by Karl Marx. Published under a Creative Commons license. Photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.