Pakistan’s refugee crisis predates Europe’s by several decades. Islamabad currently plays host to 2.7 million refugees in total, including 1.5 million Afghans, who face disproportionate discrimination by the Federal Government.

Last June, Federal Minister for States and Frontier Regions Abdul Qadir Baloch bluntly stated that “Pakistan cannot host Afghan refugees for any further period.” He justified his position with vague references to refugee criminality, the labour market, and cultural changes.

“The [provincial government of Khyber-Pakthunkhwa] is right in saying that Afghan refugees are hurting the economy and culture of the province, in addition to their involvement in crimes.”

Baloch’s statements are fairly standard, though this wasn’t always the case. During the 1970s and 1980s, when many refugees first entered Pakistan, nationalist discourse was less intense because of larger strategic concerns. When the Soviet-Afghan War formally began in December 1979, a sizeable number of refugees were recruited into the Mujahideen, and were tolerated as useful projections of American and Pakistani power in that conflict.

Once the situation changed after Soviet withdrawal, and the end of the Cold War, the United States provided less humanitarian aid and refugee support, and Pakistan shifted towards supporting the Taliban as a reliable ally in Kabul. Refugees were forgotten, and the ones who fought in the Mujahideen were quickly overshadowed.

Since the 1990s, Afghan refugees have been scapegoated for economic problems, and increasingly hated for anti-social behaviour. This is why Baloch feels empowered to criticize them, with references to the cultural harm they cause, sounding very similar to right-wing populists disparaging asylum seekers in Europe.

The War on Terror has led to new concerns, with a surge in terrorism across Pakistan, at a time when a NATO-backed government had taken control in Afghanistan. Pakistan has responded by pushing for stronger borders and deportations, arguing that refugees are an internal security threat.

Between 2002 and 2015, Pakistan deported 3.9 million refugees to Afghanistan, arguing that it is safe as a result of the NATO intervention, despite the Taliban making gains as a grassroots insurgency. Interestingly, Germany appears to be taking a similar position, with Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière saying that refugees and asylum seekers can be sent to “islands of safety” in major cities like Kabul.

Asif’s firmness reflects an increasingly aggressive stance from Pakistani military and civilian institutions following the Army Public School Attack in Peshawar on December 16, 2014.

Following the attacks, which killed 145 people, including 132 children, the 2015 National Action Plan was passed, calling for the registration of Afghan refugees in point 19. The Pakistani government has sought to stop refugee flows, and force people to return to Afghanistan. Not surprisingly, Pakistani police have terrorised Afghan refugees, with Human Rights Watch finding evidence that “Pakistani police have pursued an unofficial policy of punitive retribution that has included raids on Afghan settlements; detention, harassment, and physical violence against Afghans; extortion; and demolition of Afghan homes.”

Hence the rise in the number of Afghan refugees headed to Europe, which is why they are now the second largest group applying for asylum behind Syrians.

It is useful to end by thinking about what is absent from public rhetoric. Pakistani officials may not admit to this overtly, but many of their misgivings about Afghan refugees are driven less by terrorism than a concern about demographics, that was arguably inherited from the British.

Whether through the military, or civil society, Pakistani nationalism is currently driven by an ideology that is centred on the Punjab, making state officials hesitant to accept (and integrate) large migrations of non-Punjabi Afghans, who are monolithically described as “Pashtun” because that is the most threatening population.

By pressing for deportations, and placing severe restrictions on daily life for Afghan refugees, bureaucratic and military elites in Punjab are attempting to safeguard their own ethnic privileges in the state. Otherwise, the rapid growth in non-Punjabi populations could lead to long-term instability, as Pakistani minorities begin to mobilise against entrenched structural inequalities.

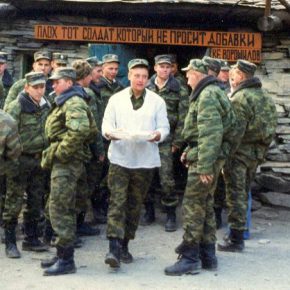

Photographs courtesy of Gustavo Montes de Oca. Published under a Creative Commons License.