As part of his series This Age of Migration, humanitarian commentator Paul Currion examines why more states than ever are erecting walls in reaction to migration, and the dangerous emergence of a migration-industrial complex.

The explorer Thor Heyerdahl once said, “Borders? I have never seen one, but I have heard that they exist in the minds of some people.” He should have known better.

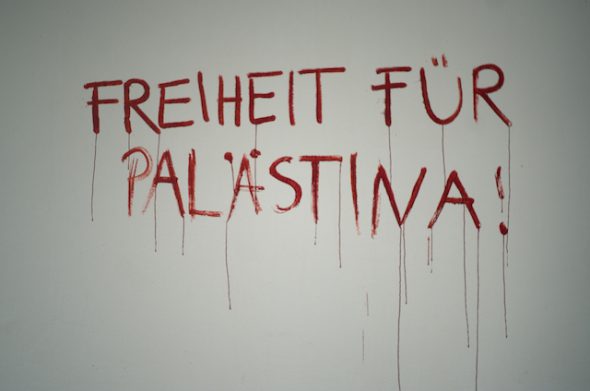

Some borders have been visible for a long time, and they’re becoming more visible all the time. The Great Wall of China is the most famous historical example, begun way back in the fifth century BCE. But recently, walls have gone viral.

It’s hard to keep track of exactly how many of these border fences there are now, but a 2015 study by Ron E. Hassner and Jason Wittenberg confirms that construction is accelerating. Over half of the border barriers erected since World War II have been built since 2000. It’s too easy to see these border walls as simply a demonstration of spatial arrogance. Instead, we should view them as symptoms, and hence the basis of our diagnosis of an existing problem in the body politic.

These walls come in many flavors. Some are hotly debated, such as Israel’s Separation Barrier with the West Bank; others are nearly invisible to the international community, such as the Moroccan Wall in Western Sahara. Some states can afford the best, especially if somebody else is footing the bill – such as the Great Wall of Jordan, now costing half a billion dollars – while others struggle with the budget, as with Kenya’s anti-terror wall on its Somalia border.

Technology enthusiasts will be pleased to learn that following the smart city, we will now have smart fences: Turkey’s new Syrian border fence will include a smart tower every 1,000ft (300m) featuring “a three-language alarm system and automated firing systems” supported by zeppelin drones. It appears that we’ve entered a new arms race, one appropriate for an age of asymmetric warfare, with border walls replacing ICBMs.

Another familiar trend from the Cold War is also re-emerging. Turkey’s fence will be built by the military electronics company ASELSAN, and we have to assume that many of the other fences are also being built by private contractors, rather than by governments themselves. If we combine that with the involvement of private companies such as Serco in immigration detention facilities, then the outlines of a migration-industrial complex start to emerge.

As the Cold War came to be replaced by the War on Terror, border barriers have often been framed as the state’s response to terrorist acts, but they’re also a distorted mirror image of terrorist intentions. Both rely on the “propaganda of the deed,” actions rather than words, to tell their story. I’ve written previously how the nation-state is a fiction. In the same vein, border walls are an attempt to give concrete form to that fiction. Building a wall is telling a story, but what kind of story is it telling?

Walls gain their meaning because of who waits on the other side, as the poet C.P. Cavafy knew: his poem Waiting for the Barbarians describes an empire not just fearing an invasion, but actively preparing for it. In the poem, however, the barbarians never make an appearance, leaving the citizens of the empire to wonder: “And now, what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? They were, those people, a kind of solution.”

If the barbarians are a kind of solution, we are back to the question: What kind of problem do we have? The barbarians can be defined however the wall-builder wants: currently, “Muslims” are the barbarian of choice. Yet both the study mentioned earlier and a separate 2015 study by David B. Carter and Paul Poast found that there was “a significantly higher probability of wall construction” between “separate economies with very different levels of development.” Contrary to populist rhetoric, it seems that states aren’t frightened of Muslims so much as they’re frightened of the poor.

In this context, it’s telling that migration is sometimes framed in terms of infection – metaphorically and literally. In this view, poverty is seen as a transmissible disease, and borders are the membrane around the state, protecting it from that perceived infection – membranes that need to be thickened. An alternative – and more constructive metaphor – might be to see the international community as a body, and population movement as blood circulating around that body. While unrestricted blood flow might be undesirable, border walls are sclerotic in nature, more likely to cause a heart attack.

Europe now leads the way in erecting walls to keep people out, and has shown that border walls can work – perhaps not as well as the claims that are made for them, but well enough. The reason that they work is hinted at in Hassner and Wittenberg’s study, which noted that many border walls are constructed by authoritarian regimes. Border walls work if they are part of a wider policy framework that includes state-sanctioned repression – either in the country building the wall, or in countries on the other side.

Not only is building a wall easier for a more authoritarian state, but a wall will also tend to make the state more authoritarian, as it seeks to defend it. Yet the Berlin Wall – which was likely at the front of Angela Merkel’s mind when she considered the refugee crisis – should remind us that authoritarian states don’t construct walls solely to keep people out, but also to keep them in. We’re so busy building that wall on the border, we may not notice that particular infection until it’s too late.

“This Age of Migration” is our commentary series that reflects on some of the currents running beneath the crisis, from border fences and biometrics to the role of innovation and the rhetoric of invasion.

This article originally appeared on Refugees Deeply, and you can find the original here. For important news about displacement and forced migration, you can sign up to the Refugees Deeply email list. Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit.