This is the first of two articles on the party national conventions that are currently going on in the United States. These gatherings have precipitated more than the usual measure of handwringing this time around, especially on what passes for the left wing of American politics.

One needn’t look far to find impassioned warnings about the collapse of the Republic, partly due to the candidacy of Donald Trump and its collateral effects on the public sphere, partly due to the fact that Hillary Rodham Clinton is the dictionary definition of the hold-your-nose-and-vote political candidate. These portents of doom fight for space in public discourse with the optimistic partisans of both candidates, enthusiastically touting the capacity of one or the other to bring about a new and greater age.

The underlying secret of American politics is that both parties are versions of the same thing. That is to say, both are representatives in one way or another of the concentrated political and economic power of the top .1 % of the income distribution. The fanaticism with which the devotees of each side attempt to impress the differences on the public sphere merely serves to emphasize their fundamental unity. The choice in American politics today is not one of stark political alternatives, but whether you’d rather have the up-armored Humvee driving down your street piloted by a psychopath or a sociopath. It’s not that the choice is meaningless; it’s just a matter of what kind of risk exposure one is comfortable with.

Today’s Republican Party is a perfect embodiment of psychosis at an organizational level. This is not so much a matter of the individuals involved as of the institutional aggregate: the standard vote acquisition structure of a modern mass political party synergizing with a voter base fully involved in the schizophrenic episode of Western modernity. And perhaps one might note at this point that designating the party as psychotic isn’t meant to suggest simple detachment from reality (although that sort of thing is very much in evidence). Rather it is a matter of a perception of perpetual existential threat emanating from all points. As Baudrillard once wrote:

“[T]oday we have entered into a new form of schizophrenia – with the emergence of an immanent promiscuity and the perpetual interconnection of all information and communication networks. No more hysteria, or projective paranoia as such, but a state of terror which is characteristic of the schizophrenic, an over-proximity of all things which beleaguer and penetrate him, meeting with no resistance, and no halo, no aura, not even the aura of his own body protects him. In spite of himself the schizophrenic is open to everything and lives in the most extreme confusion. He is the obscene victim of the world’s obscenity. The schizophrenic is not, as generally claimed, characterized by his loss of touch with reality, but by the absolute proximity to and total instantaneousness with things.”

It is this state of terror generated by the interacting flows of information and violence that shape the modern world that motivate the gun-wielding, disaster-prepping, government averse white guys who now compose the greater part of the voter base of the Republican Party. The party itself enters into a symbiotic relationship with this base, making over its convention from the staid celebration of democratic continuity that such events were in the middle decades of the 20th century, to a forum for tales of Armageddon and thinly veiled (sometimes completely open) racism.

As regards racism, it is tempting (even sort of comforting) to entertain the thought that the overt and unapologetic way that people in the Republican party are now giving open voice to it is some sort of knock on effect of the rise of Trumpism. So, when eight-term Iowa congressman Steve King asked a reporter from Esquire, “Where did any other subgroup of people [i.e. other than white people] contribute more to civilization?” we might be tempted to think that his openness with regard to such bigotry (combined with an apparently total ignorance of the historical record) was just a function of the way that Trump has made saying horrific things in public ok.

But King has a long history of repugnant public utterances, and no one in the party has gagged on them up to this point. So that novelty of Trumpian bigotry is a bit of a hard sell.

The entirety of the Republican platform is fear, and it is this fear that engenders and empowers psychosis. This is, to be sure, not the first time that it has been suggested that the modern world at large was a source of mental illness. From Deleuze and Guattari’s association of schizophrenia with the structure of capitalist society to the (much weirder and more violent) activities of Wolfgang Huber’s Sozialistisches Patientenkollektiv, the association of madness and the modern order has a considerable lineage. But the idea of a major social institution devoted to the promotion of psychosis as a basis for social organization is, to my mind, novel.

The use of fear is certainly not new. The use of apocalyptic language in politics is one of the common features of the republic from its earliest days until the present. Perhaps this has to do with the powerful influence of millenarian Protestantism in American culture. In any case, it is certainly not limited to one or the other end of the political spectrum. While the Republicans brought us Willie Horton, it was the Democrats who demonized Barry Goldwater in 1964 by juxtaposing the image of a defenseless child with the a nuclear explosion. Fear as a powerful tool is a powerful motivator.

But today’s Republican Party has taken fear from motivator to raison d’etre. We are beleaguered by terrorists who could be waiting around every corner. We are beset by illegal immigrants bent on taking jobs from hardworking Americans, or simply draining our entitlement budgets (and giving this money to lazy foreigners is one of the few things worse than giving it to lazy citizens). Our social and sexual mores are under attack by women unwilling to accept the roles that they have traditionally occupied. An overweening government bent on enslaving the citizenry, instituting socialism, and introducing foreign substances into our precious bodily fluids threatens our guns and our money. It is not merely the temporal nearness of apocalyptic threats, but their physical proximity. They are literally all around us, invisible but omnipresent.

And what is it that this political schizophrenia demands? A father figure capable of simultaneously neutralizing the threats to our physical space as well as resolving the chaotic breakdown of the system of signifiers that structure the American psyche. Trump is the father who resolves the anomie and invasive threats that are the defining feature of modernity. He is also the great permitter, the man who will allow the repressed, politically incorrect truths that all sensible people know to be spoken aloud. And he is the thaumaturge who will convert the hegemony of ascertainable facts into a magical world in which the things we feel have a decisive reality all their own.

This represents a decisive shift in American politics. It is no longer the case that politics is organized along a continuum from left to right. The Democrats have slid seamlessly into the Reaganite niche abandoned in all but rhetorical terms by their Republican rivals. The Republicans have, to paraphrase Captain Willard from Apocalypse Now, skipped from the whole program.

There was a time in American politics in which the business of government seemed to be becoming so obscenely technical as to have gone beyond the reach of all but the specialists and technician. From Max Weber through Joseph Schumpeter, scholars raised the question as to whether politics would eventually become a sort of technical arcana, and that democracy would thereby be completely emptied of substance. But a truly democratic element has returned, and perhaps one might now take account of the wisdom of the old adage, about being careful what we wish for.

For the democracy that has now returned is not the moderate culture described by Tocqueville, but the radical and dangerous extremism described by Michael Mann in his The Dark Side of Democracy. Mann argued that societies organized on the basis of a particular demos (generally ethnically defined) exhibited tendencies that led toward (although did not necessarily precipitate) mass killing.

To be clear, it is not being suggested here that the Republican Party is on the verge of mass murder, much as the idea of compulsorily transferring several million people does have some very creepy overtones. But the current state of the party’s rhetoric is unapologetically centered on one particularly demographic segment of the population (white men), who view themselves as a threatened and declining minority.

The GOP’s presidential candidate has unequivocally presented himself as a savior who will protect and defend all that the demos holds dear. What remains to be seen is if the centrifugal force of his and his followers’ hateful utterances overcomes the centripetal force of their fear.

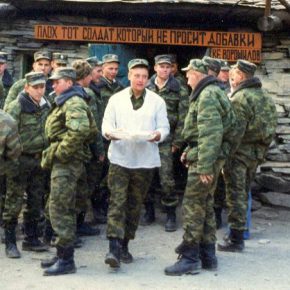

Photographs courtesy of Katerkate and Jeffrey Scism. Published under a Creative Commons license.