For 21 months, from June 25, 1975 to March 21, 1977, India was under a state of emergency. The immediate cause of the Emergency was an Allahabad High Court ruling on June 23 that disqualified Indira Gandhi from parliament as a result of “campaign irregularities” surrounding her re-election, pending a final decision by the Supreme Court, though it occurred in the context of wider turbulence.

The behaviour of Indian parliamentarians, and police, during the period, which saw nearly two years of widespread arrests, press censorship, and severe restrictions on civil liberties, is broadly similar to the current situation in Turkey. This extends beyond the obvious parallels of state brutality, panicked electorates, strong institutional support for illiberal politics, and rhetoric about a cryptic “internal threat.” Importantly, in both cases, embattled leaders use legally justifiable states of emergency to push anti-democratic politics through existing political institutions, which reflects deep systemic problems in liberal democracy.

First, some background about the Emergency is necessary, before discussing the overlap between Turkey and India. Following the 1971 Lok Sabha election, in which her Congress Party won a large majority of 352 seats, Gandhi quickly became a regional leader after a massive victory in the 1971 India-Pakistan War. The conflict led to Bangladeshi independence, and a permanent edge over the Pakistani Army.

Her standing quickly faded after a string of economic problems, including mass inflation caused by the 1973 oil shock, decreased industrial production, and rising unemployment, corruption, and poverty. Trade union militancy culminated in the 1974 railway strike, accompanied by student protests in Bihar where independence leader Jayaprakash Narayan came out of retirement to call for a “total revolution.”

The Allahabad High Court ruling thus came at an especially difficult time, particularly in light of an opposition victory in Gujarat assembly polls earlier that month. Moreover, two years earlier, in September 1973, a CIA-backed coup took place against Salvador Allende in Chile. Allende’s overthrow and execution shocked leaders across the Third World, partially explaining Gandhi’s paranoia. In Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan likely feels similarly after the collapse of Mohammed Morsi’s government in Egypt.

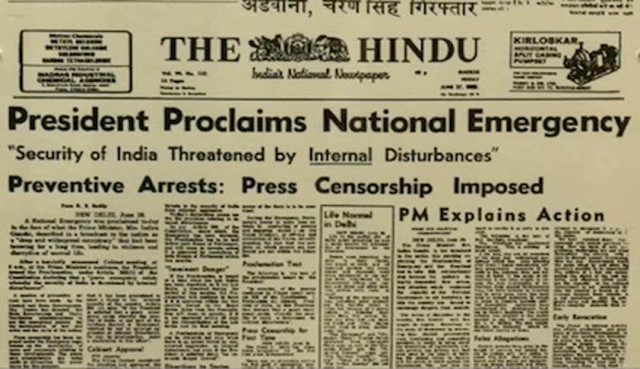

When Narayan reacted to the High Court ruling by calling for a weeklong satyagraha (non-violent protest in the vein of Mahatma Gandhi) on June 25, 1975, to press for Gandhi’s resignation, and urged police, government employees, and the armed forces not to obey government orders, she had enough. That night, Gandhi called a secret meeting that night to discuss the crisis. The next morning, she made an unscheduled radio broadcast to announce that a state of emergency had been declared just before midnight.

During the night of June 25 and 26, police arrested all major opposition leaders, including socialists, and the now-governing conservative Bharatiya Janata Party. The Indian government had suspended civil liberties by July 4, and banned four major oppositional factions: Jamaat-e-Islami, Ananda Marga, the Hindutva RSS, and the Naxalites. According to the Shah Commission, called in 1977 to examine the period, over 100 000 people were arrested, including 30 MPs, with many prisoners being tortured while detained without trial.

Despite the extremity of the violence, Indira Gandhi continued to be supported by the vast majority of her party, except for a small number of MPs who were quickly suspended. As a result, the Congress Party was able to make sweeping changes to the Indian constitution. These included the 38th amendment, which prevented courts from reviewing government actions during the Emergency, the 39th, which protected India Gandhi from Supreme Court action over her election case, and the 42nd, which curtailed fundamental rights, and officially declared India to be a “socialist secular republic.” Gandhi also received praise from the Communist Party of India, and the Soviet Union, which famously described the Emergency as a “blow to a right-wing plot” (despite Naxalite revolutionary communists receiving the brunt of the violence).

Historians treat the Emergency as a threat to liberal democracy, that was undone by widespread resistance. Daily papers like the Indian Express defiantly printed empty editorial spaces. Government inquiries like the Shah Commission quickly restored public confidence. Constitutional amendments passed by Prime Minister Morarji Desai’s Janatha Party, elected after snap elections in March 1977, pushed back against the Congress Party’s changes.

This reading overlooks that the Emergency occurred in full accordance with Indian democracy, not in spite of it. The Congress Party supported Indira Gandhi with a strong majority in parliament. Furthermore, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed declared a state of emergency through Article 352 of the Indian constitution, which states:

A Proclamation of Emergency declaring that the security of India or any part of the territory thereof is threatened by war or by external aggression or by armed rebellion may be made before the actual occurrence of war or of any such aggression or rebellion, if the President is satisfied that there is imminent danger thereof.

The Indian government had previously declared states of emergency during the 1971 India-Pakistan War, and 1962 India-China War, citing “external aggression.” Indira Gandhi made the the argument that the security of India was “threatened by internal disturbances,” which is a dubious reading of the clause.

However, the problem is less that she was opportunistic, and more that the constitution even allows for such measures. Article 352 is a remnant of British colonial law, which allowed for sweeping police crackdowns in the event of foreign invasion, and local insurgency. Under the British, emergencies were declared in order to put down significant opposition to colonial rule. The obvious problem with Article 352 is that the purpose hasn’t changed. It can always be used to quell domestic opposition, when the central government feels under threat. That is the larger problem with constitutions that allow for states of emergency, and it extends beyond India.

The Emergency was clearly an abuse of state authority. Gandhi used emergency powers to evade corruption charges, harass opponents, preside over brutal state violence, and begin a notorious mass-sterilisation campaign. Yet despite her illiberal politics being an overreach, they never fully broke the limits of what she was actually allowed to do. Although Gandhi was elected as leader of a shaky, but established democracy, her increasingly dictatorial stance was considered legitimate, because it was framed by a condition of national emergency.

Similarly, Erdoğan, while acting in an authoritarian manner, hasn’t actually moved beyond the limits of his power as a ruler. Article 120 of the Turkish constitution allows for states of emergency to be imposed “at a time of serious deterioration of public order because of acts of violence.” This was certainly true of the failed July 15 coup d’etat. As a result, Erdoğan now legally enjoys sweeping authority, which he is using to crack down on dissent. It is easy to condemn him as authoritarian, but that avoids the larger question: why does the Turkish constitution allows its leaders to potentially embrace that level of control in the first place?

States of emergency make it far too easy for social unrest, whether real or perceived, to lead to representative institutions being undermined. Numerous constitutions have provisions for them, whether in Turkey, India, France, Egypt, or Pakistan. There are legitimate reasons for a state of emergency, such as when natural disasters demand a rapid deployment of state resources. However, clauses like Articles 352 and 120 effectively mean that seated governments always have the ability to suspend the rights and freedoms that are supposed to limit their actions. As a result, liberal democracy is structurally unstable: the rule of law can easily disappear in the right situation, whether an attempted coup in Turkey, or Narayan calling for a “total revolution” in India.

As Turkey absorbs the fallout of Erdoğan’s authoritarian power play, it will become increasingly necessary to deal with this problem. India has made huge strides since the Emergency, such as through a nimble and increasingly virtual press that can quickly disrupt government attempts to take control. However, Article 352 has been left unchanged. It would be foolish to think that something like the Emergency can never happen again, with a retooled approach by a different leadership.

If Turkish democracy is to be repaired, then oppositional forces must go beyond a simple restoration of liberal norms, which is what happened in India. The constitution also needs to be reevaluated, in order to reduce the potential for state authority to be used to crush dissent in the name of stability.

Photograph courtesy of The Hindu.