Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon has made it clear she wants to hold a second independence referendum. The prospect of Scotland breaking away from the Union was predicted by many Remain commentators. Ironically, the nationalist core of the Leave vote could be responsible for the end of the United Kingdom. Brexit opened the door to the unknown, and we are now drifting through uncharted territory.

Unlike the majority of the English left, I was sceptical of Scottish independence during the 2014 referendum campaign. Not that I romanticise the Union, or doubt the capacity of the Scottish people to run their own affairs. Nor do I buy into the suspect argument that the Scots have been saving the English from themselves. On the contrary, the Scottish ruling class was a participant in British capitalism and imperialism for centuries. The history of Protestant Scottish reaction is somewhat inconvenient for the nationalist mythology.

In fact, Scottish history has many features we would recognise as English. The rise of empiricism and free-market economics are apart of the Scottish Enlightenment. At the same time, the Scottish ruling class joined the Union on the side of British imperialism after its own failed attempt at colonialism. The basis for Scottish nationalism may have been laid by the emergence of a working-class out of the Highland clearances, as well as Irish Catholic immigration.

Yet it was only with the end of empire and social democracy that the SNP can come to power. As part of the New Labour project, Tony Blair devolved power in Scotland to allow for greater self-government. This was intended to be a concession given Scotland’s place in Labour Party history. Instead the opening was the beginning of the end for Scottish Labour. Nationalism took hold as Labour went into decline after the Brown years.

Of course, Scottish independence could be a great opportunity for market forces. The power of monetary policy may still be held by Westminster and this could constrain any independent government in its policies. Likewise, it would be possible for corporations to hold the state to ransom – threatening to divest the fledgling economy – to cut taxes and spending. A race to the bottom between England and Scotland could follow.

The cause of Scottish independence has since become a conduit for the hopes of leftists. “Freedom!” cried the SNP. “We’re with you!” the English left shouted back. They were soon echoed by Welsh and Irish socialists. Sinn Fein and Plaid Cymru were jubilant at the possibility of an independent Scotland. The death of the Union would redeem the aspirations of Irish republicans and Welsh nationalists. It would also mean a historic crisis for the British establishment.

A rupture with the past could force a constitutional crisis in Westminster, whereby a whole series of questions would have to be answered. The Prime Minister would have to resign, and the ruling party may be forced from office by the following election. People often say this would guarantee a Conservative majority, but it would actually mean more boundary changes. Likewise, it would also open up a space for much- needed devolution within England. It could even serve to jump-start the debate on electoral reform.

Today’s political situation seems to vindicate the progressive arguments for Scottish independence. Brexit has thrown into question the future trajectory of the UK, and the Conservative government is in the driving seat. Meanwhile, the majority of Scottish people wanted to stay in the European Union. The second vote is potentially a necessary intervention to push back against the reactionary forces mobilised by Brexit.

The Union has done much to preserve and entrench inequality in Scotland, where the richest 10% have 273 times as much wealth than the poorest 10%. The richest 100 men and women increased their wealth from £18 billion to £21 billion in 2012. While 60% of the country is owned by less than 1,000 people. This is why many Scottish socialists see a radical case for independence. It would end the centuries old holding action over class society.

It has been suggested that Sturgeon really just wants to force Theresa May to keep Britain in the single market. After all, the price of oil no longer favours independence, and the eurozone crisis makes the euro an unlikely replacement for the pound (even with the recent loss of value). There may be a cautious wing of the SNP, which fears it could lose a second referendum. But this is a cynical reading. It’s certainly the case that the party’s base wants out.

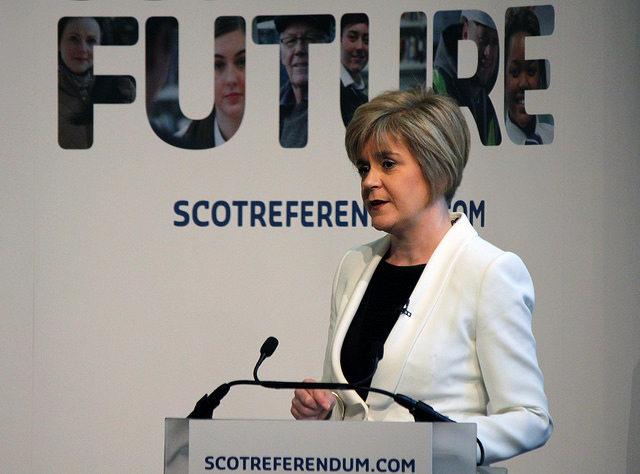

A second referendum would be a high-risk strategy for securing a soft Brexit. Sturgeon would be in danger of jeopardising the SNP’s future if the vote were just a ploy. It’s not wise to play chicken, and Sturgeon is anything but an unwise woman. She is one of the few serious figures in UK politics right now. It wouldn’t surprise many observers if the SNP got its second vote and won. Though it is conceivable that the Conservatives would try to avoid this at all costs.

The May government is working hard to avoid certain disaster. May could try to quell the SNP threat with greater funding or autonomy, however, the real issue is still Europe. In the end, the Conservatives might be forced to face their own internal divisions by the Scottish government. Staying in the single market would placate the SNP, but it could trigger a Tory rebellion on the backbenches. Chaos is a real possibility for the UK government.

Photograph courtesy of Scottish Government. Published under a Creative Commons license.