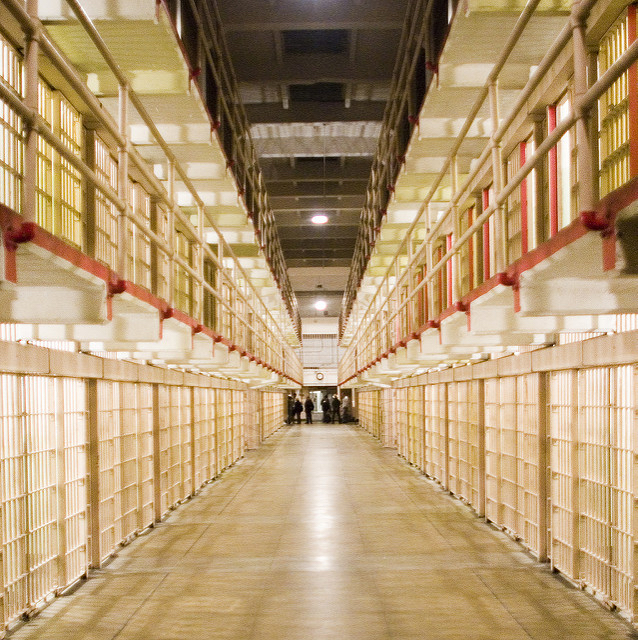

It is well-known that there are currently 2.4 million people in US prisons and jails. What is less-known is that they write and are producing a new wave of American literature.

While a few writers such as Jimmy Santiago Baca, Leonard Peltier, Reginald Dwayne Betts, and Ken Lamberton have gained recognition and awards, others who remain largely anonymous include such as poets Diane Hamill Metzger, Ace Bogess, and Ezekiel Caligiuri, radical writer Raymond Luc Levasseur, or the hundreds who send their work to the annual PEN contest for imprisoned writers. The work of prison writers fills crudely-produced webzines as well as sophisticated enterprises such as the American Prison Writing Archive. Amazon’s self-publishing platform, CreateSpace, offers a huge selection of prison erotica written by prisoners keeping up the imaginative tradition of their fellow prisoner Marquis de Sade.

Arthur Longworth’s Zek is part of this literature of mass incarceration emerging from US prisons. The novel’s title (gulag prisoner) and prologue invoke Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, a novel from a very different period and place of mass incarceration. Longworth borrows the narrative frame of a day in a prisoner’s life, the device of seeing through a prisoner’s eyes how the game of survival gets played, and even such details as floor-cleaning assignments and pervasive cold. Zek is located in an eastern Washington prison rather than the Siberian taiga, yet despite expectations the American institution is a far crueler environment than the Russian labor camp that Solzhenitsyn describes.

The deeper comparisons and contrasts between the two books are political. Solzhenitsyn published his novel in 1962 in the Soviet Union’s leading literary journal, Novy Mir, with authorization from Nikita Khrushchev since it served his de-Stalinization purposes. The publication of Ivan Denisovich, taken as a sign that Soviet camps could now be discussed, provoked a brief outpouring of reminiscences of camp life that authorities quickly suppressed. De-Stalinization did not mean a liberal state with free speech.

By contrast, Zek arrives from the bottom up, not the top down. Longworth completed the novel in 2005 and it circulated in manuscript copies, an American prison samizdat, for a decade before its publication. The novel has been banned in the Washington State prison system after having been smuggled out for publication. The publisher, Gabalfa Press in Seattle, is a tiny independent operation dedicated to “writing from the margins.” Zek appears as a small voice within the US political heterogeneity rather than a nation-shaking publishing event in the former Soviet Union’s monopolistic political homogeneity.

And yet the question should be why Zek and other US prison literature fail to disturb America’s conscience? The Russians have given far more social attention to prison writing, including Dostoevsky, Shalamov, Mandelstam, and more recently Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina of Pussy Riot. In the United States, by contrast, the best-selling prison memoir of recent years is John McCain’s Faith of My Fathers that recounts Vietnamese imprisonment and solitary confinement as the endurance of a national hero when it is better understood as the result of US imperialism and war in Southeast Asia. Americans respond better to accounts of themselves imprisoned overseas, such as Billy Hayes’s Midnight Express, than they do to accounts of what occurs in US prisons.

Longworth pronounces an anathema against prisons. Anton, an admired work crew leader, speaks to the novel’s political message when he tells the protagonist Jonny that the day is coming “when we’ll take this fucking place over and burn it down. That’s the day I’m waiting for, Jonny—the day we stop this shit. The day we stop these motherfuckers from doing this to anyone else.” That is very distant from Solzhenitsyn, a neo-Czarist who thought the real problem with Russian prisons was that they should have held communists instead. Ivan Denisovich was a narrative of prison survival; Zek’s final message concerns prison abolition.

Jonny, the narrator, is an imprisoned Everyman. He is not bad but prison teaches him mostly how to return to prison, which he will do eventually by learning to cook meth. The prison around him seethes with barely subdued violence towards which he learns to avert his eyes. One day in Jonny’s life includes witnessing a guard-tower shooting in the yard while waiting for chow, transporting a weapon secretly for a fellow prisoner, standing point to watch for guards while one prisoner rapes another, and at the end of the day cleaning blood and teeth from the floors and walls of a room where guards have beaten a prisoner mercilessly. Longworth, who has spent significant time in solitary himself, makes clear the invidious effects of such close confinement on human personalities.

Longworth’s strength lies in the detail of realistic narration and ability to adopt an unpretentious psychological point-of-view. Jonny’s thoughts outline choices, avoidances, risks, and penalties of failure in a prison environment. Secondary characters such as his cellies Corey, Matt and Seth gain life and body rather than remain mere props. The plot carries readers easily through the daily routines and especially the sensory experiences of prison. Perhaps a questionable moment in the novel was a brief unnecessarily didactic epilogue that reveals the fate of Jonny and other characters, but that is a quibble. Longworth possesses a fine sense of craft and innate writing skill.

Arthur Longworth continues to serve a mandatory life sentence in Washington State for a murder committed in 1985. While his parole applications have been turned down, Longworth has become an eloquent advocate for prison education and reform. His ‘Mass Drownings’ talk is a compelling exposition of the injustice and human loss created by mass incarceration. Longworth’s writing reminds us, should anyone forget, that one of the strongest forces against mass incarceration is the voice of prisoners themselves.

Photographs courtesy of Thomas Hawk, Jobs for Felons and MyFuture.com. Published under a Creative Commons license.