When Paula, aged 15, announced her engagement to Franz, elder sister Selma was horrified. Instead of congratulating her, Selma slapped her sister’s face. Nevertheless, Paula and Franz married and had a daughter, Käte.

They settled in Halle an der Saale, where Franz was a banker. An old photograph still in my possession shows my Onkel Franz proudly posing in front of his automobile, appropriately dressed in breeches, boots and gloves.

Paula was father’s baby sister. She was small and dainty. She parted her black hair in the middle and wore it in a traditional Gretchen style braided over her ears. That is the way she appears in her wedding day photograph with a spray of flowers pinned to her bosom. She kept her Gretchen Frisur and never changed it.

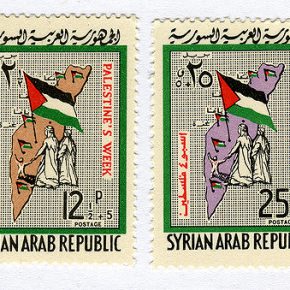

When, in 1931, things began to go wrong for Jews in Germany, father urged his sisters and their families to leave. My grandparents and brothers were no longer alive. Father had four surviving sisters. Else and her husband went to India. Erna and her family escaped to Belgium. Selma went to Italy and later to Australia. Paula, Franz and daughter Käte sailed to Palestine.

Onkel Franz, Tante Paula and their daughter Käte rented a small flat on the third floor of a new three-storey building on Nahmani Street. A large 19th century portrait of a side-whiskered patriarch dominated their living-cum-dining room.

Onkel Franz was the ideal uncle. He taught me to play Rummy and let me win the first round. He was a truly warm, truly gentle, patient man. He had to be, married as he was all these years to Paula, whose dainty appearance was quite misleading. She knew what was right. And above all, what was wrong.

This knowledge Paula applied to perfection when she came to Nahmani Street. There she could observe, thanks to the close view, all the wickedness, laziness and a myriad other faults to which I was prone. It must be said, however, that she could be unusually generous. Depending of course on my behaviour.

In her Biedermeier cabinet, Paula kept a display of miniatures, tiny alabaster dogs and cats with blue glass eyes. There was a lacquered two-tier Chinese jewellery box which she gave me. Also. a small gold wristwatch, which I managed to lose later on. All the same, her voice keeps coming back to me in its less endearing Germanic tones.

She must have thought it her duty, as an authority on what’s right and what’s wrong, to scold me and remind me of my guilt, in case I had forgotten. There was, of course, some truth in her reproaches. Whereas at age five I was already able to read the five-page novel about a red cow, I had great trouble with my sums and didn’t do well at school. Maths was the cross I had to bear for the rest of my school days, which I began with such promise.

Tante Paula and Onkel Franz never spoke a word of Hebrew, and if they did know a few basic words, I never heard them spoken. They did, however, recognize the need to provide Hebrew language lessons to their daughter Käte. Dr. Rubinstein, who supplemented his income by giving private lessons, was chosen to teach her.

Dr. Rubinstein was an excellent teacher and young Käte made good progress. Everything was going well until one day Käte and Dr. Rubinstein announced their engagement. Whereas Kate was young and pretty, Dr. Rubinstein seemed to me to be much older and he had a rather large nose.

Onkel Franz and Tante Paula were horrified. The nose didn’t bother them. Dr. Rubinstein was of Eastern European origin. Ein Ostjude. What could be more humiliating than an alliance by marriage with a Jew from Eastern Europe, worse still, from Poland! That did not stop Käte and Dr. Rubinstein from marrying. You will ask me what his first name was. The answer to that is that I have no idea, nor did Käte’s parents bother to find out. They always addressed him as Dr. Rubinstein.

Onkel Franz pinned high hopes on the production of a new type of roll-up blinds. But the venture collapsed and he lost a lot of money. My uncle and aunt left their Nahmani Street home and moved to a small cottage in Tel Litwinski, a 30-minute bus ride from Tel Aviv.

Enterprising and hard working, my Tante Paula grew vegetables and strawberries in her garden and sold them to the local greengrocer. During World War II, Onkel Franz found work in the neighbouring military camp. His job was washing dishes.

When peace broke out, German reparations followed. Paula and Franz were able to enjoy their remaining days in Switzerland, in comfort and free of care. I never saw them again.

Photograph courtesy of Frans de Wit. Published under a Creative Commons license.