Following the first Gulf War, the United States focused on preventing security and economic disruptions by Iran and Iraq, as their bitter rivalry throughout the 1980s shook the Persian Gulf region, threatening global energy supplies, and international shipping lanes.

However, when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, the US decided to use Iran to help isolate it, setting the stage for the reemergence of Tehran as a preeminent regional power, much to the chagrin of America’s two main allies in the region, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

But Iran was unwilling to enter into a relationship with Washington along terms that the US could accept. So when the US policy of “dual containment” was inaugurated in 1993, it was meant to contain both Iran and Iraq without resorting to an alliance with either, though this of course failed.

In practice, the limitations the United States faced in containing both countries simultaneously without turning to the other for support meant that by 2003, the stage was set for a military confrontation with Iraq and a further deterioration in relations with Iran.

No-fly zones over the Kurdish north and Shia Arab south were established in 1992 in Iraq, too late to prevent the defeat of insurgencies that rose up mere months after Gulf War I ended. Iraq’s sanctions regimen was initiated in 1990 and renewed continually up until 2003 under the auspices of Congress and the UNSC. UN weapons inspectors remained in Iraq until 1998, when they were first expelled en masse; a second UN effort ended in 2002.

Iraq’s known WMD programs were of much greater concern to the United States than Iran’s, despite the priority Israel and the Gulf states increasingly afforded to Iran’s nuclear capabilities. Even though in 1995, Saddam’s son-in-law defected to Jordan and told the world that he had had the WMD materiel destroyed, Saddam had continued to play a successful cat and mouse game with inspectors, concealing his WMD’s non-existence. To maintain his deception – in order to deter the Iranians – he preemptively confessed that he had indeed lied to the world, just as his son-in-law said.

In doing so, the Iraqi strongman dangled the possibility that he had even more hidden secrets.

This defused the bombshell revelations, but came back to haunt him a decade later when a different US president called his bluff, yet invaded anyway.

When Saddam Hussein expelled inspectors in 1998 as part of his ongoing WMD deception, the US launched Operation Desert Fox to “degrade” his (non-existent) capabilities. This demonstrated just how much the US mission in Iraq had become centered on WMDs that did not necessarily exist. Saddam’s bluff meant that the world was growing weary from the cost of containment.

Arab allies, especially, called for leniency against Iraq due to their fears of Iran and its growing nuclear program. An impoverished, isolated Iraq could not possibly help contain Iran in the Gulf as it had done in the 1980s. Today, the regional calculus has not changed significantly. Iran is seen as a clear and present danger, far more so than the instability caused by the ongoing Israel-Palestinian conflict, and perhaps on the same level as ISIS in some capitals.

The United States ignored these calls, though. Regime change entered the lexicon. Whereas past efforts had been abandoned due to Clinton’s judgment that the time was not yet right, the Republican Congress passed the Iraqi Liberation Act in 1998 and Clinton accepted its provisions, which explicitly made regime change the end goal of dual containment there.

The collateral loss of life from the sanctions (of several hundred thousand Iraqis by some estimates) was becoming a liability and international support for the sanctions was slipping, hence the return of the previous administration’s fantasy scenario that a palace coup would solve everything. Clinton set down the parameters for an endgame with Saddam, though it was the Bush Administration that actually made the transition from containment to regime change.

In a surprising development in 1998, though, the Iranian-backed Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI) was made eligible to receive US aid from the Act, alongside the pro-American Iraqi National Congress, because SCIRI had opposed Saddam since 1982. But, even from here, there was no starting point on the shared animus to Saddam.

Meanwhile, the Iraqi dictator retained his grip on power and his inner circle suffered little, even though his military capabilities never recovered and the country’s civil society (and population) fractured apart. Partly due to these pressures, Saddam Hussein increasingly Balkanized his own security apparatus. That, combined with the larger impact of the eventual US invasion and dismantling of the Iraqi state, has had lasting effects on Iraqi society, even in the civil war against the so-called Islamic State.

Supreme Leader Khamenei chose to focus on Islamism in one country, albeit while still trying to export its influence. He sought to build a nuclear deterrent and to channel the Islamic Revolution into grandstanding against Israel after time and again failing to export the Iranian model to the Gulf states (even better ties with Yemen, an outlier in so many ways from its neighbors, was at best a partial success for Tehran).

Iran found a more receptive Levantine audience, and used its patronage to inject itself into the wider conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, who by then had effectively lost their Cold War Arab patrons now aligning with the US-led order.

While the resistance of so many other UN members to Iran-specific sanctions meant that Iran had more breathing room than Iraq did, there was always consistent pressure from Congress to increase sanctions on Iran, even unilaterally, and especially when Israel (and to a lesser extent, the Gulf states) voiced concerns that rapprochement was buying Iran’s nascent nuclear program time.

Such consistent pressure overrode what other interests there were to restore trade and diplomatic ties. Outreach efforts by Iranian reformists were never given the priority that the architects of dual containment said they would grant Iran.

It was the hardline Iranian leadership that presented the most significant roadblocks to expanding on a handful of US goodwill gestures made in the 1990s. Because anti-Israelism, nuclear research, and state-sponsored terrorism were all core components of Iranian policymaking both at home and abroad, it became impossible for the United States to reach a modus vivendi even with the reformist Khatami government after 1997. President Khatami was undermined by the intransigence of the mainstream religious and military establishment, which included a plague of assassinations carried out by hardliners against dissidents.

The killings had the tacit approval of some top officials hoping to embarrass the president, and in this respect they succeeded. But even if Khatami had not been so constrained, Iran’s grand strategy was completely incompatible with US interests at the time.

Indeed, the two most infamous terrorist attacks outside of Lebanon attributed to Iran against Western interests in this period were the 1992 Buenos Aries bombing (targeting Israelis), and the 1996 Khobar Towers bombing (targeting Americans) in Riyadh. Likely carried out by the Iranian-backed Hizbullah al-Hijaz, the latter attack put paid the prospect for serious dialogue, let alone detente.

By 2003, Iran’s insurance policy of holding al-Qaeda facilitators in-country under a loose house arrest, and continued nuclear ambitions, meant that there would be no serious talks between the US and Tehran over Iraq or the nuclear issue.

Iran was dubbed a member of the “Axis of Evil” in 2002 by President Bush, despite the two countries finding common ground in Afghanistan the year before, against the Taliban. With the Bush Administration still hinting it might strike Iran, Khamenei and his IRGC were fast-moving to exploit the opportunities a Second Gulf War would present in Iraq, promoting Shi’ite politicians, and helping it fight al-Qaeda guerrillas.

Hence, Iran’s strong position today, in Iraq, and its growing authority, in Syria and Lebanon. Little did Washington understand how it was empowering Tehran, and where it would end up playing a new role as power broker, as far afield as Israel’s northernmost border, and the southernmost part of the Saudi peninsula, in Yemen.

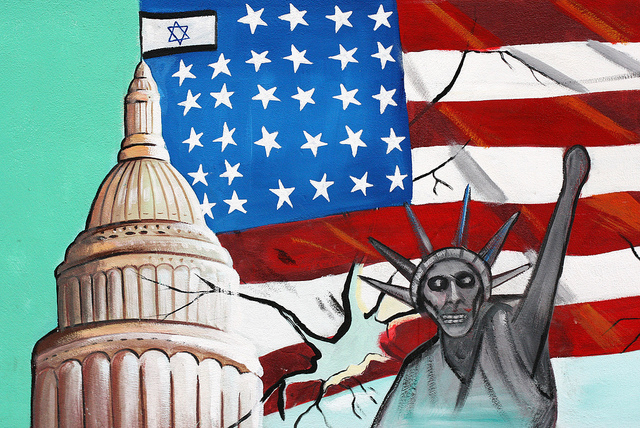

Photographs courtesy of Yeowatzup, Mehr News Agency, Kamyar Adl, and Casey Hugelfink. Published under a Creative Commons license.