Amid the anti-migration rhetoric of the incoming Trump administration, Preethi Nallu meets resettled families in the midwestern city of St. Louis, whose communities have helped resuscitate areas of their new hometown.

FEW U.S. METROPOLITAN areas transform as noticeably from one neighborhood to the next as St. Louis.

On the drive toward the Gateway Arch on the banks of the Mississippi River, in the original heart of the city, the roads turn from smooth to ragged and become peppered with potholes. Ritzy malls are replaced by thrift shops. The affluent neighborhoods of the counties give way to poverty and neglect in the city.

On a boulevard that cuts St. Louis into two, marking a striking racial and economic divide, Hang Nguyen Trinh and her family, originally from Saigon, own the best-known Vietnamese restaurant in the area.

For the past 25 years, Pho Grand has been attracting customers from opposite sides of the Mississippi River to a part of St. Louis that is regarded as a success story for the resettlement and integration of refugees. The family-run restaurant has become such a fixture that most locals cannot remember when “the Hangs” came to live in Middle America, off the usual migrant path.

A surprising number of migrants and refugees have been able to cross the city’s physical and psychological divisions, breathing new life into its dying neighborhoods.

St. Louis is a city of seeming contradictions. At one point, it was staunchly segregated. Yet it now has one of the largest per capita refugee populations among U.S. metropolitan areas. Images of the city from the early 1900s – when it was a gateway to the West – depict a bustling metropolis, with its population reaching more than 800,000 by the 1920s. But following decades of general recession and outward migration, the population of the city’s urban core dwindled to about 320,000 by 2010. As a result, entire neighborhoods were emptied, with shop fronts indefinitely shuttered. Following the decline in American manufacturing during the 1970s, the city desperately needed new workers and job creators – “warm bodies,” as local reporters describe it.

Arriving refugees resuscitated neglected parts of the inner city and over time started their own enterprises, bringing new work opportunities to locals, and better infrastructure and development to their areas. When Trinh opened Pho Grand restaurant on Grand Avenue in 1989, it was the first Vietnamese restaurant in the region. The avenue, in a protected heritage area, was bereft of residents and commerce. Two and a half decades later, her restaurant is surrounded by several other businesses offering ethnic cuisine on a boulevard that is frequented by office workers by day and university students by night. The businesses attracted banks to further invest in the area, which resulted in better connectivity with the rest of the region.

Not far from Trinh’s restaurant lies Little Bosnia, a neighborhood that resembles a quaint Eastern European village. Restaurants serve Bosnian specialties such as pljeskavica (minced beef) and cevapi (sausage) and conversations on the streets switch back and forth between Bosnian and English.

Resettlement in St. Louis

The city’s positive track record with resettlement is the product of generations of work by St. Louis’ local resettlement programs and by refugees themselves. Successful integration has hinged on meeting the refugees’ three main practical needs: community, identity and employment.

Nationwide, a history of creative responses to different displacement crises and changing federal laws have filtered down to more support and services at the local level. Organizations such as the International Institute in St. Louis – one of 300 such assistance agencies across the United States – help new arrivals with accessing education, employment, healthcare and rehabilitation. In turn, newly empowered refugee communities have become entrepreneurial in spirit. This is notably the case in St. Louis, where refugees have opened businesses and bought homes in otherwise depressed areas of the city.

The current anti-immigrant and anti-refugee fervor in the U.S. belies the country’s history of successfully integrating refugees in places like St. Louis that are off the usual migration trajectory. Most recently, President-elect Trump has vowed to send back up to 3 million undocumented migrants and restrict the United States’ refugee resettlement program, which is the largest in the world and has the most stringent vetting procedures of any route to enter the country.

Despite the fear-mongering, a look at successive generations of refugees and their integration into the U.S. shows that providing resources and support to refugees during their resettlement period is an investment that can benefit both the refugees and the American communities hosting them.

In St. Louis, Refugees Deeply met three families from different waves of displacement, who arrived in the U.S. during varying political climates – Vietnamese refugees who came in the 1980s and 1990s, Bosnians in the early 1990s and 2000s and Iraqis in more recent years. Each generation said their ability to regain their financial independence and immediate access to education helped them become part of the social tapestry and, eventually, feel at home as “New Americans.”

From Saigon to St. Louis

If integration is a mutual process, in which U.S. communities and new arrivals influence each other’s cultures, then food is a valuable litmus test.

Pho Grand is a case in point. It is pronounced “fuh” and not “faux,” as self-respecting connoisseurs of the traditional Vietnamese broth at the restaurant – mostly middle-aged white men – will gently scold you, while proclaiming the restaurant “the best in the Midwest!”

“Most people are astonished that I was a refugee at some point. I try to tell them that a refugee is like anyone else, just without a country to call home,” Trinh says with a smile.

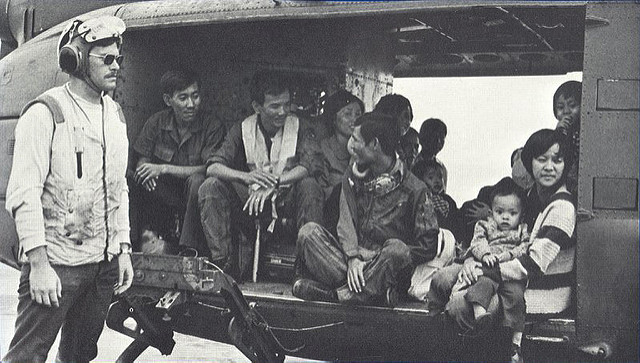

Trinh calmly recounts how she watched the rising plumes of smoke engulfing her home, as she sat in silent consternation, with nearly 4,000 other people, cowering on the deck of a departing commercial ship. It was 1975, and Saigon was burning down to the ground.

“When the communists came from north to south and bombarded the city, we took off to the pier, amid a life and death situation. I saw bombs falling, I saw dead people in the streets. I was 11 years at the time, so old enough to remember,” explains Trinh.

They sailed into the pitch blackness of the South China Sea, with the water and the sky bleeding into each other in the starless night. Trinh thinks she was at sea for four days, feeling as if she was trapped in the Bermuda Triangle, never to be found again. The memories remain so raw, “it could have happened yesterday.”

She cannot ever forget seeing a grown man put a pistol to his head, on the deck, among the listless passengers. “He was right there in front of us, with his insides splattered on the floor. He was filled with regret over leaving his wife and children behind.” She also remembers seeing many people panicking as the ships departed, and jumping into the water to swim back to shore.

Their ship managed to reach Hong Kong, where her family applied for asylum through the U.S. resettlement program in 1980. They were among the 120,000 “Vietnamese boat people” who arrived in the U.S. within 12 months of the country creating a special resettlement program.

Changing Responses to Displacement

Resettlement patterns in the U.S. are driven by an interlinked mix of “international politics, federal policy and local contingency,” according to journalist Kathy Gilsinan, and Trinh’s story includes all three factors.

Of the 1.3 million Vietnamese living in the U.S. today, roughly 70 percent arrived seeking asylum from the 1980s to 2000. Trinh is among them.

Tens of thousands settled in St. Louis, drawing their extended family members over the decades. During the 1990s, large numbers of Vietnamese who were in the “re-education camps” of the new communist government were also granted asylum on humanitarian and political grounds. Tens of thousands of them were relocated to St. Louis.

The history of refugee resettlement in the U.S. dates back to the aftermath of World War II, when more than 600,000 Europeans entered the U.S. over several years. In that era, the U.S.’s approach to refugee resettlement consisted of creating ad hoc laws to cope with each unfolding displacement crisis. In the 1950s and 1960s, in response to a wave of refugees from Hungary and Cuba, the U.S. bestowed “parole” authority to the office of the attorney general to expedite admissions of civilians in need of urgent humanitarian protection. By 1975, the U.S. applied this approach to the Vietnamese crisis and set up the Indochinese Refugee Task Force and a domestic integration program.

But it was the 1980 Refugee Act that became a “decisive turning point” by creating new political asylum laws and local assistance programs, and solidifying the relationship between resettlement agencies and the federal government. Vietnamese and other Indochinese refugees were the first wave of refugees to benefit from the newly created laws and local support systems. Since then, the U.S. has resettled more than 3 million displaced people, making it the largest facilitator of refugee resettlement in the world.

Building ‘Little Bosnia’

“The memory of how we left our home is seared into my memory, more than anything else,” says Narcisa Przulj Symank from Bosnia.

Symank (whose maiden name was Przulj) fled the brutal siege on Sarajevo in 1991 with her mother, brother and extended family members on one of the last convoys to leave the city. She remembers the abrupt departure, with the vehicles filled beyond capacity with women, children and elderly people. Her father, like most other men, would have to find his own way out of Sarajevo, which had been taken over by Serbian nationalist forces.

The Przulj family was placed in sleepy Fenton, south of St. Louis, with expansive stretches of land as far as their eyes could see. It was a stark contrast to the arresting images of Sarajevo that would appear alongside global headlines for the next decade.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uY-d6t6pW3o

In Fenton, “it used to take my father 30 minutes to walk to the closest gas station when he wanted to buy cigarettes,” Symank says. The town has since filled up with more homes and businesses.

Bosnian refugees arriving in St. Louis followed in the footsteps of the Vietnamese. In their case it was “secondary migration” – resettled refugees who chose to relocate to St. Louis – that led to a sizable community. Bosnian refugees arriving in the 1990s were motivated by existing support networks established by their compatriots who had been migrating to the Midwest since the 19th century and had set up private initiatives to help the new arrivals. They also found help from public resettlement services and opportunities created by the city’s own need for labor and development.

Large areas of the southern part of the city received a new lease on life from the Bosnian arrivals, who restored and rented vacant homes and started businesses, which in turn led to new infrastructure such as schools, hospitals and public spaces, and ultimately more jobs for the locals.

Despite arriving with little more than the clothes on their backs, the community plugged into the existing diaspora network in the U.S., maximized the services provided by the state and even formed their own chamber of commerce. With an average income of $83,000 a year – 25 percent more than those who were born in the U.S. – migrants in St. Louis, many of them resettled refugees, have become an asset to the local economy.

Symank, 33, a lawyer and partner at one of the top law firms in the Midwest, is one example of the influence that resettled refugees in St. Louis can carry. She says that the public support system and sponsored services that were already in place in St. Louis jump-started her integration. Symank was able to attend school just three weeks after arriving in the U.S.with assistance from the International Institute. She is part of the 70,000-strong community of Bosnian migrants and refugees in St. Louis, the biggest diaspora outside Europe.

But the road to the “American Dream” was convoluted. It entailed moving from one hostile territory to another for five years, explains Symank.

With a Bosnian Muslim mother and Orthodox Christian Serbian father, Symank and her brother did not find solace on either side of the divide. They spent a year in Croatia before relocating to Serbia via Hungary. At the Serbian border, the guards would not let them through the checkpoint without the correct documents to prove their religion and nationalities.

“I remember my mom and her sister had belts with wads of money hidden under their clothes. It was incredibly dangerous to go, the way we did from one border to another,” she says. “My mom actually pinched my brother to get him to start crying, hoping they would feel sorry for us.” Having left the Hungarian side of the border, they sat amid fields in what looked like a no man’s land, fully aware that at any moment they could be arrested or worse. Seeing their father arrive on the Serbian side, to receive them, their first contact in a year, “it was our first sight of relief,” says Symank.

The family applied for asylum in the U.S. and were among the 131,000 Bosnians who were resettled in the country from 1992 to 2007. The Migration Policy Institute reports that 142,000 people were admitted in the U.S. in 1993 alone, most of them fleeing the Balkan wars. It remains the most recent peak year of arrivals in the country’s history.

Many Bosnians entering the U.S. were deeply traumatized, many suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder for years. The Bosnian Refugee Center, set up in St. Louis in 1994 with the help of public and private funds, helped their transition process. Such support systems played an important role in providing psychosocial support to refugees arriving in the U.S. who were no longer in “emergency mode” and more likely to benefit from counseling and therapy.

The Next Generation

Despite arriving a decade apart, both Trinh and Symank were able to maximize the freedom and opportunities that the U.S. offered and the resettlement program harnessed for them. The Vietnamese and Bosnian communities in St. Louis now exert palpable political, economic and social influence.

Both women also hope that their experiences will not become relics of a bygone era in U.S. history. They have watched anti-refugee rhetoric during the recent presidential election campaign with vexation.

As anti-Muslim sentiment gains ground in the U.S., Symank says that the successful integration of Bosnian refugees should serve as a reminder that Muslim communities can succeed in the U.S. Both Trinh and Symank are adamant that while resettlement takes time and resources, it comes with numerous benefits to both refugees and the locals.

While generations of refugees have successfully resettled in St. Louis, in recent years the city has lagged behind other areas of the country in absorbing new migrant communities. Economists argue that while immigration has already raised local wages by an average of $600 per year, encouraging larger flows would increase the income of the area by as much as 7 to 11 percent. There appears to be ample scope for St. Louis to keep welcoming migrants and refugees in order to continue strengthening its economy.

Amid the caustic portrayal of refugees as an economic drain on domestic resources in the U.S., St. Louis’ example could be replicated in other urban areas in need of manpower and investment. Economically dispirited zones exist in most Midwestern cities after their populations moved to the east and west coasts, and the emergence of interstate highways “broke the urban fabric to facilitate the depopulation of inner cities,” according to Washington University in St. Louis researchers.

With inner city neighborhoods in cities like Detroit, Milwaukee and Cleveland still in tatters, there remains empty land in need of people, and thus a reason for the strategic placement of resettled refugees.

‘Good Migrants’

Despite its successful history of absorbing refugees, current U.S.resettlement rates cannot keep pace with the accelerating levels of displacement around the world, especially the Middle East. For instance, Iraq was the top origin country of refugees resettled in the U.S. in 2013 and 2014, accounting for 28 percent of total arrivals. But the number of Iraqis coming to the U.S. declined last year, even as the rise of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) brought more conflict and mass displacement. In total, 2 million Iraqis have fled the country’s borders, while another 1.5 million from Mosul could join the 1.7 million internally displaced. With over 5 million displaced Syrians, the needs are colossal.

Salman Taha, who moved to St. Louis from Iraqi Kurdistan two years ago with his wife and two daughters, appears unfazed about their acceptance into U.S. society. Originally from a village close to Erbil, he was able to move to the U.S. more easily because of his work with U.S. forces stationed there.

“Kurds and Americans started being friends from 1991, the first time Iraq fought Kuwait. From that day we had good communication between Kurds and Americans. So that’s a very good thing,” Taha says.

The U.S has forged close ties with the Kurds since the 1970s. Iraqi nationals who work with U.S. troops can apply for the Special Immigration Visa (SIV), and are eligible for the same benefits as refugees. A total of 11,000 such visas have been issued since 2006, but only over 5,000 Iraqi nationals have been admitted this way. The SIV program promised to admit at least 25,000 nationals from Iraq and Afghanistan, but is now under threat of closure.

Given the recent cooperation between the U.S. and Kurdish forces to oust ISIS from northern Iraq, Taha feels that relations have strengthened, and “Kurds are welcome in the country.”

Taha, an enthusiastic Trump supporter, says he would have voted for the Republican Party candidate had he received his U.S. citizenship before the polls.

His views on politics and migration are vastly different from Trinh’s and Symank’s, who view Trump as a threat to minority rights. Taha feels he is among the “good migrants” that Trump will continue to patronize with incentives.

Sitting in his home, which is flanked by his neighbors’ pro-Trump flags on their front lawns, he shares videos that he says prove Trump’s “love for the Kurds.”

It is too early to tell whether Taha will receive the same level of acceptance from his local community as Trinh and Symank have. But it is clear that he is already benefiting from the support systems and services in place.

For Symank’s family, who escaped the 1,425-day Sarajevo siege of the Bosnian War – the longest held on a capital city to date – the current siege on Aleppo hits close to home. Symank is dismayed to find Balkan states that experienced large-scale displacement, of which she says her family was an infinitesimal part, now shunning desperate asylum seekers at their borders.

These days, when Trinh and her mother watch footage of refugees arriving by the boatful in Greece and Italy, they are gripped by a haunting familiarity and relive the feverishness they had felt at sea.

The parallels between their experiences of migration and the common humanity that binds their narratives are not lost on the older generations of refugees resettled in the heart of America.

“How things have not changed,” remarks Trinh, allowing a moment of respectful silence in the conversation.

In the U.S. system, the president is vested with the power of setting the resettlement quota. Incoming President Trump’s call to impose a moratorium on certain refugees has filled both resettled Americans and asylum seekers with a sense of foreboding.

This article originally appeared on Refugees Deeply, and you can find the original here. For important news about displacement and forced migration, you can sign up to the Refugees Deeply email list. Photograph courtesy of Manhhai. Published under a Creative Commons license.