Joseph Daher is a Swiss-Syrian academic and activist. Originally from Aleppo, Daher is a staunch opponent of the Syrian Ba’ath regime. He maintains the website Syria Freedom Forever, which is dedicated to building a secular and socialist Syria. In his latest book Hezbollah: The Political Economy of the Party of God, Daher takes apart the misconceptions around Hezbollah and its role in Lebanese society.

In the years since the Arab Spring began the international left has become increasingly divided over Syria, particularly as the revolution turned into a civil war with plenty of interference from outside. As a result, the left has diverged into at least three main camps: those who see Western imperialism as the main foe, and others who claim Western intervention is vital for the Syrian rebels to triumph. But these two postures are not the only positions available.

There is another strain on the left, those who see no hope and no justice in either American or Russian involvement. Rather the case for Syrian emancipation requires a critical account of the different international forces at work in the civil war. Not just Russia and the United States, but also the roles played by the Gulf powers, Turkey and Iran. This is the premise of every serious analysis. And this is a vital part of Daher’s standpoint.

The following Souciant interview with Joseph Daher examines the poison gas attack on Khan Sheikhoun in the context of the civil war, as well as the interventions of foreign powers, the class character of the Assad regime and the politics of the Syrian opposition.

The gas attack on Khan Sheikhoun stirs memories of the Ghouta attack in 2013 for a lot of observers. Why do you think the Assad regime resorts to such measures?

First of all, I would like to say that since the chemical attacks Eastern Ghouta in 2013 until the gas attack on Khan Sheikhoun, many attacks with chemicals occurred and on a regular basis since 2013. This despite the fact Assad declared in June 2014 that chemical weapons had been removed from Syria to be destroyed. These kinds of attacks have become so frequent in Syria that most have not made it to the international news headlines.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) has actually documented 167 attacks using a toxic substance since the first U.N. resolution in September 2013. Forty-five of those attacks were carried out after August 2015, when the U.N. passed a resolution establishing the Joint Investigative Mechanism to identify perpetrators using chemical weapons in Syria. In 2017, SNHR documented 9 attacks using toxic substances by regime forces.

The chemical attack was another step in the murderous campaign to destroy what is left of the popular opposition to the Assad regime. After putting under siege and destroying Eastern Aleppo, the most important center of the popular and democratic opposition, and forcing the survivors as well as the survivors from other besieged opposition areas to go to Idlib, the regime is now concentrating its forces on bombing the civilian population in Idlib and Aleppo provinces. Syrian regime has actually focused its use of poison gases on opposition-held areas where 97% of its chemical attacks targeted opposition-held areas while 3% of the attacks were carried out in ISIS-held areas.

The objective of chemical weapons is clearly to instil terror in people, while there are few ways for civilians in liberated areas to protect themselves. This also showed the impunity with which the regime conducts its war against the Syrian people.

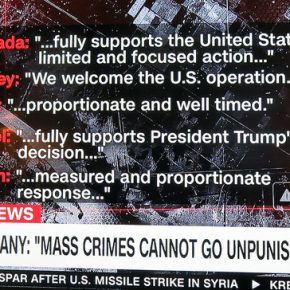

Many people have called for a military intervention against the Assad regime and we’ve just seen the US bomb a Syrian government airbase. What’s your view of Trump’s missile strike in response to Khan Sheikhoun?

I think we need to understand why for some sections of Syrians, especially within the country, were satisfied or happy at US bombing of a regime’s military base from which the chemical attack was launched. After more than 6 years of a constant war and in total impunity of the regime against the Syrian people, this was the first time a military base of the regime was targeted for its murderous actions.

This said, no kind of optimism or illusions should be put in US administration in bringing anything positive to the Syrian people to achieve democracy or relieve even their pain. Many Syrians in liberated areas also understand this very well, as we can find many testimonies saying for example that the strikes were not to punish Assad too harshly, but to make him understand that he must not cross the “red lines”, in other words the use of chemical weapons, while it is okay that its military forces continue to use barrel bombs, vacuum rockets, cluster bombs, phosphorus weapons, etc.

Residents of Khan Sheikhoun actually suffered from regime’s bombing few days after the chemical attack on Saturday, 8th of April, which killed one woman and wounded several other people. Regimes and Russian warplanes also bombed last weekend various provinces, resulting in the deaths of new civilians.

The USA have not changed their strategy in Syria: the priority is still “the war on terror”, in other words Daesh, and try to reach stability in Syria in maintaining the regime, with at its head or not Assad. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who is expected to visit Moscow on April 12 for talks with Russian officials, actually said on ABC’s This Week program there was “no change” to the U.S. military posture toward Syria.

The way also the US bombing occurred showed that they did not want to hit too “hard”, to say the least. Moscow officials confirmed that they received advanced warning from the U.S. about its strike on Syria, while according to some testimonies, regime soldiers were prepared for the 35-minute strike and, in advance, evacuated personnel and moved equipment out of the area. Within 24 hours of the strike, regime’s warplanes were actually again taking off from the bombed Shayrat air base. So for the moment, a change of strategy of the USA is still to be seen, although we also have to be careful as well as Trump is unpredictable, as he likes to say.

In addition to this, recent American airstrikes in Mosul, Aleppo and Raqqa, which are supposedly aimed at stopping ISIS, have also brought about large civilian death tolls. They have been some of the deadliest since U.S. airstrikes on Syria started in 2014. On Saturday 8th of April, At least 15 civilians, including four children, were killed in a suspected US-led airstrike on Saturday near the city of Raqqa. This shows that greater U.S. military intervention in Syria will only lead to more death and destruction. According to Airwars, during the month of March alone, as many as a thousand civilians have been killed by U.S. airstrikes in Iraq and Syria in the name of the “War on Terror”.

In general, since coming to office, the Trump administration has given every indication that its goal is to promote authoritarian, racist, sexist Arab leaders and strengthen the repressive environment of the Middle East. These realities not only reveal the Trump administration’s motives but also compel us to condemn all the states that are carrying out wars against innocent civilians in the Middle East: The Syrian and Iranian regimes, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Israel, all the other authoritarian regimes in the region, IS, Al Qaida, and other religious fundamentalist movements, as well as Russian and Western military interventions.

These moves are all part of an imperialist logic and the maintenance of authoritarian and unjust systems. They all oppose the self-determination of the peoples of the region and their struggles for emancipation. Hence, anti-war activists whether in the Middle East or the West need to address all forms of repression and authoritarianism, and condemn all forms of foreign intervention against the interests of the people of the region, instead of limiting their criticisms only to the West and Israel.

Clearly, no peaceful and just solution in Syria can be reached with Bashar al-Assad and his clique in power. He is the biggest criminal in Syria and must be prosecuted for his crimes instead of being legitimized by international and regional imperialist powers.

Some people on the left have tried to defend the Syrian Ba’ath regime as a ‘lesser evil’ to Islamic State and jihadi rebels. How would you describe the character of the Assad regime and its role in the region?

This perception of these sections of the left is completely wrong and destructive of the “lesser evil”. The solution to struggle against Islamic fundamentalist movements does not lie in the collaboration with authoritarian regimes like the Assad regime, quite on the opposite. When it comes to the IS and similar organizations, it’s necessary to tackle their root causes: authoritarian regimes and international and regional foreign interventions.

IS emerged as the result of crushing the space for popular movements linked to the 2011 uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa. The interventions of regional and international states have contributed to ISIS’s development as well. In addition to this, neoliberal policies have impoverished the popular classes, together with the repression of democratic social and trade union forces, have been key in providing ISIS and Islamic fundamentalist forces the space to grow.

The left must understand that only by getting rid of these conditions can we resolve the crisis. That means we have to side with the democratic and progressive groups on the ground fighting to overthrow authoritarian regimes, defeat the counter-revolutionary Islamic fundamentalists, and replace neoliberalism with a more egalitarian social order in Syria and the region. Without addressing the political and socio-economic conditions that allowed and enabled the development of the IS, its capacity of nuisance or that of other similar groups will remain.

The solution is therefore of course to oppose the IS and other reactionary and jihadists forces, which as a reminder the Ba’ath regime has encouraged their developments at the beginning of the popular uprising in Syria by liberating the worst jihadist and Salafist personalities from its prisons, while killing and repressing democratic and progressive forces, but also and especially the barbaric, criminal and authoritarian regime of the Assad family.

The Assad regime is the main responsible of the disaster in Syria and of the exile of millions of Syrians. Both actors are barbaric and they feed themselves and are therefore to be overthrown to hope to build a democratic, secular and social society in Syria and elsewhere. This requires the support of democratic and popular movements that oppose these two counter revolutionary forces (authoritarian regimes and Islamic fundamentalist forces) and different forms of international (United States and Russia) and regional imperialisms (Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Israel and Turkey) that are all fighting against the interests of the people in struggle in the region.

The Assad regime is an authoritarian, capitalist and patrimonial state using various policies such as sectarianism, harsh repression, tribalism, conservatism, and racism to rule, very far from being anti-imperialist and secular as presented by some of its supporters. The patrimonial nature of the state means the centres of power (political, military and economy) within the regime were concentrated in one family and its clique, the Assad, similar to Libya and Gulf monarchies for example, therefore pushing the regime to use all the violence at its dispositions to protect its rule.

In the economic sector, for example, following the accession to power of Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian regime engaged in an increased and accelerated process of implementation of neoliberal economic policies. The latter have benefited in particular a small oligarchy, which had proliferated since the era of his father, because of its mastery of the networks of economic patronage and their loyal customers. Bashar al-Assad’s cousin, Rami Makhlouf, the richest man in Syria, perfectly embodied this Mafia-like process of privatization conducted by the regime in favour of its owns. Makhlouf controlled huge sectors of the economy directly or indirectly, according to some nearly 60%, thanks to a complex network of financial holdings.

In addition it has played a destructive role regionally, collaborating with various imperialist forces. We shouldn’t forget that Assad’s regime collaborated with the second gulf war in 1991 with US led coalition. Syria participated in 2001 in the war on terror working with US security officials. In 1976, Syria intervened in Lebanon to crush the Palestinian resistance and the Lebanese national movements, a coalition of nationalist and leftist forces. The regime has also historically instrumentalized and cooperated with jihadist groups after the Iraqi invasion by the USA in 2003 or Fatah al-Islam in Lebanon in 2007, while liberating most of the jihadists and Islamic extremists in the various amnesty calls at the beginning of the Syrian revolutionary process.

In what ways does the regime headed by Bashar al-Assad differ from the way his father ran the country?

The structures and core of the Ba’ath regime were built by Hafez al-Assad at its arrival in power in 1970 and they have rivalled by their murderous repressive campaigns. This being said some real changes did take place.

From 2000, Bashar al-Assad strengthened the patrimonial nature of the state in the hands of the Assad family and relatives through a process of accelerated implementation of neoliberal policies and the replacement of sections of the old guard by relatives or close individuals to Bashar al-Assad.

The first years of Bashar al-Assad in power were actually concentrated on establishing himself as the main decision maker and marginalizing the centers of power within the regime challenging this aim. This process was achieved as we have seen in 2005 with the resignation and then departure of Abdel Halim Khaddam in exile in 2005. It is at this period that the social market economy strategy was launched. It constituted in many ways the culmination of at least two decades of regime-bourgeoisie reconciliation.

The social market economy strategy led to a shift in the social base of the regime constituted at its origins of peasants, government employees, some section, with at the heart of the regime coalition were the crony capitalists – the rent-seeking alliance of political brokers (led by Bashar’s mother’s family) and the regime supportive bourgeoisie. It was this bourgeoisie that funded 2007 Assad re-elections and the one that expressed its support for the ruling regime by propaganda and proclamations in the first months of the revolution when demonstrations of support for the Assad regime were still a pressing need for the regime, in addition to funding after militias loyal to the regime.

This shift was paralleled by disempowerment of the traditional corporatist organizations of workers and peasants and the co-optation in their place of business groups, while a new labor law ended what the regime’s section pushing for neoliberal policies called overprotection of workers. The corporative and fierce nature of the state under Bashar al-Assad was even more weakened than at the time of Hafez al-Assad, relying exclusively in coercive policies as the corporative organizations were undermined considerably. In other words, the reconfiguration of authoritarianism under Bashar did not strengthen it but on the opposite limited even more its popular basis.

Large section of the society left out of the liberalization process, particularly from villages to medium sized cities, would be at the forefront of the uprising. The policies of the regime were opposing the interests of the popular classes and serving and benefiting a small minority of crony capitalists linked to the ruling class. This is the principle contradiction the Syrian popular masses had and have to face until today.

In terms of foreign policy, the major change was the deepening of relations with Iran and Hezbollah, not only considered tactical allies, which we can use on some occasions, but strategic ones.

The absence of democracy and the growing impoverishment of large parts of Syrian society, in a climate of corruption and increasing social inequality, prepared the ground for the popular insurrection, which thus needed no more than a spark.

It’s often said that the Syrian political opposition differs from the military front. To what extent have Islamists taken over the frontline in the struggle against the state? Does this pose a problem for the revolution?

We should remember first that the Syrian grassroots civilian opposition was the primary engine of the popular uprising against the Assad regime. They sustained the popular uprising for numerous years by organizing and documenting protests and acts of civil disobedience, and by motivating people to join protests. The earliest manifestations of the “coordinating committees” (or tansiqiyyat) were neighborhood gatherings throughout Syria.

The regime specifically targeted these networks of activists, who had initiated demonstrations, acts of civil disobedience, and campaigns in favor of countrywide strikes. Their qualities as organizers and their democratic and secular positions undermined the propaganda of the regime, which proclaimed that “armed Islamic extremists” constituted the entire opposition. Large numbers of dissidents were imprisoned, killed, or forced into exile on the back of this lie.

Despite this Syrians continued to play an important role in the ongoing revolution and led various forms of popular resistance against the regime. By early 2012, there were approximately 400 different tansiqiyyat in Syria, for example, despite intense repression from regime security forces. On top of this, Syrian revolutionaries would later endure the authoritarianism of various religious fundamentalist forces (like IS, Al-Qaida, Jaysh al-Islam and Ahrar al-Sham), which enjoyed wide expansion across the country and attempted to co-opt the revolution or crush its democratic and inclusive message.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xz7efPYGiH0&t=130s

Activists also established popular organizations and put together democratic, social, educational, and cultural activities. Local radio stations and newspapers sprang up. Many campaigns opposing both the regime and Islamic fundamentalist forces emerged. All the while, activists and grassroots organizations strove to deliver an inclusive message against sectarianism and racism. These organizers challenged some armed groups’ authoritarian practices and opposed Islamic fundamentalism.

Tragically, each defeat of the democratic resistance strengthened and benefited the Islamic fundamentalist forces on the ground. The rise of Islamic fundamentalist movements and their dominations on the military scene in some regions was negative for the revolution, as they did not shared its objectives (democracy, social justice and equality).

These movements not only acted as a repellent for the far majority of religious and ethnic minorities, and women with their sectarian and reactionary discourses and behaviors, but also to sections of Arab Sunni populations in some liberated areas where we have seen demonstrations against them, more especially to large sections of the middle class in Damascus and Aleppo. They attacked and continue to do so the democratic activists, while they often tried to impose their authority on the institutions developed by locals in areas liberated from the region, bringing often resistance from local populations against their authoritarian behaviors.

As I understand it, the Syrian revolution established democratically elected councils to run public services and provide water, food, education and health-care in the areas under rebel control. How do these councils relate to the armed struggle?

By the end of 2011 and toward the beginning of 2012, regime forces started to withdraw, or were expelled, by opposition armed groups from an increasing number of regions across Syria. In the void they left behind, grassroots organizations began to evolve, essentially forming ad-hoc local governments.

On many occasions, popular and local coordination committee activists were the main nuclei of the local councils. In some regions liberated from the regime, civil administrations were also established to make up for the absence of the state and take charge of its duties in various fields, like schools, hospitals, water systems, electricity, communications, welcoming internally displaced persons, cleaning the streets, taking the garbage away from the city center, agricultural projects, and many other initiatives.

Local councils were either elected or established on consensus. In addition, some local councils encouraged campaigns of activists around democratic, artistic, educational, and health-related issues. It is important to note that many popular youth organizations were established throughout the country, as well free media outlets such as newspapers and radios.

These local councils represent democratic alternatives in Syria, free from the regime and reactionary movements, which is precisely why the areas in which they operate are often the most targeted by the regime and its allies. At the same time, this does not mean that problems and contradictions did not exist in some Local Councils, such a lack of women’s participation or a lack of representatives from minority communities. Still, it was impossible to ignore the way that popular power flourished in even dire conditions.

However, all the cities and neighborhoods in which there was a popular, democratic, and inclusive alternative were targeted, such as Eastern Aleppo or the city of Daraya in the province of Damascus. They are in fact still being targeted along with the civilian infrastructures on which these experiences are based. Between March 2011 and June 2016, 382 medical facilities were attacked, killing more than 700 medical workers. Assad and Putin are responsible for 90 percent of these assaults. They have also bombed other civilian institutions, including humanitarian workers, as well as bakeries, schools, and factories.

It estimated that around more than 250 valid local councils in the opposition-held areas are still operating. In mid January 2017, elections were held for the first time in Idlib to elect a civilian council of 25 representatives to manage their city, nearly two years after it was overrun captured by an armed coalition called Army of the Conquest (Jaysh al-Fateh), led by Jabhat al-Nusra and Ahrar al-Sham. Until then, it was a committee appointed by the Army of Conquest that had run the city’s affairs.

These examples of popular and democratic self-organizations are the elements most feared by the regime since 2011. Since 2011, the regime has most feared these democratic organizations, even with all their imperfections. Assad worries much less about the corrupt and exiled official opposition and the Islamic fundamentalist forces. After all, the regime’s authoritarian and sectarian practices encouraged and fostered ISIS’s, Jabhat al-Nusra’s, and other similar organizations’ development — better to have a Islamic fundamentalist foe than one that could capture widespread international solidarity and popular legitimacy at home.

The relation of local councils with armed opposition groups depended from the equilibrium of forces between these two and if the opposition armed groups had a good relation with local civilians. This said, often problems occurred between these two entities, while at the same time some relations were models to follow such as Darayya before it was recaptured by the regime in 2016 and its population displaced.

In the town of Darayya, the FSA factions were under the direct authority of the Local Council and any military operation had to be coordinated with it. The city also disposed of only one financial treasury, which managed the donations and financial assistance given to the city. The local council was in charge of distributing the funds, which were allocated to various services such as the support of the FSA factions, relief and humanitarian operations and the distribution of daily aid to the besieged population in the city. The Local Council also ordered them to avoid any kind of human rights violations and any extremist sectarian discourse or behavior.

Photographs courtesy of Beshr Abdulhadi, Antonio Marin Segovia and Maureen. All published under a Creative Commons license.