The rise of Jean-Luc Melenchon has caught the international media off guard. After ignoring the man for months, the English-speaking press is suddenly obliged to analyse the chances of the most viable left-wing candidate. Even the Anglophone left has been caught out here.

As always the English left is divided over its own concerns and strategy. Some see Melenchon as the only option in a race where the mainstream candidates are faltering. Others are suspicious of Melenchon’s platform and, in classical sectarian style, demand more purity of socialist convictions.

In short, the English left doesn’t seem to be able to make up its mind about Melenchon, but this doesn’t matter if Melenchon makes it to the second round. The French people will decide.

Nevertheless, it’s worth exploring the reasons behind this division. It appears that the English left is looking at France in terms of the crises it faces at home. Brexit has polarised the left and the questions of nationhood rests at the core of this. For better or worse, Melenchon remains stubbornly committed to the idea of the nation-state. And this draws suspicion from some quarters of the left.

Unsubmissive France

A part of this is cultural, the English left is wary of all nationalisms. This is understandable given the history of flag-waving in the British Isles. It’s not like red patriotism has ever taken hold in England. A left-wing civic nationalism has emerged in Scotland and Wales, yet English nationalism remains trapped by potent forms of ethnic and cultural chauvinism.

It is possible to appeal to patriotism in the French context given that the nation-state itself was the creation of the 1789 revolution. The dark side of French history – the empire, slavery, the civilising missions in Africa, and the capitulation to fascism – are conveniently dropped; but this mythmaking is necessary to every form of patriotism. Whether or not it is a good thing is separate from its effectuality.

What cannot be disputed is that Melenchon’s charismatic appeals to French history and culture have gripped the imagination of many people. He has successfully married a left social democratic project to la patrie. The French left may be divided over strategy and candidates, but it’s clear who stands the best chance of subsuming all left forces under one umbrella in time for the second round: Benoit Hamon and Philippe Poutou were never going to play this role.

Not only does Melenchon have the edge because of his red patriotism, he has the Front de Gauche (The Left Front) – a coalition of the Left Party (his own creation), the French Communist Party and rogue elements of the New Anticapitalist Party and the Socialist Party. This bloc has allowed Melenchon supporters to move freely outside the French ruling class and the European establishment.

It’s why Melenchon has been able to build France Insoumise (Unsubmissive France) as a Podemos-style left populist insurgency. This has granted Melenchon a great deal of credibility. The fusion of grassroots and social media activism created the basis for his candidacy to finally breakthrough into the mainstream. It sets an example for the wider European left about how to advance against all the odds.

Questions of nationhood

At the same time, there is a lot of disinformation going around. We’re told Melenchon is pro-Assad and pro-Putin because he opposes NATO in Ukraine and Western involvement in Syria. We’re told Melenchon is “soft” on racism and “hard” on immigrants. I can’t disperse all the claims here, but I will look at the debate around immigration – which is a vital one in the election.

As I understand it, Melenchon has argued for a ‘regularisation’ of illegal migrants in France so as to document and officialise migration. This seems like a good alternative to what Marine Le Pen wants, namely a racist police state based on the state of emergency. However, it is also true that the officialisation of migrants is a pre-condition for whether or not they are deported or granted residency. This is where the debate begins.

There is an ongoing debate about freedom of movement on the left. A traditional social democratic position would be that the flow of migrant labour has to be controlled under capitalist conditions because it serves as a reserve army of labour. In effect, the migrants provide cheap labour and in turn threaten the wages of workers in the host country. This is until the migrant workers can be unionised and brought into the labour movement.

The opposing view is that the free movement of labour is a progressive step forwards for the working class because it prevents the illegal status of migrant labour. After all, the existence of illegal workers is conducive to greater exploitation, not a barrier to low wages and falling standards of living. So if you want to stop wages from being undermined, you ought to throw out the possibility for illegal migration. Thus, free movement has a great deal of support on the radical left.

This is how the opening up of borders can allow for working class unity and an equal playing field. The answer to wage competition on that equal playing field is not to erect barriers, but to extend solidarity through trade unions. Yet there remains a contingent of left support for restricting immigration, and this has to be accounted for and understood. The Melenchon platform is not free from the more old-fashioned centre-left arguments about the necessity of migration controls. But it’s not inherently anti-migrant.

You can disagree with the line that border controls and workers’ rights are compatible, however, it is hardly in the same platform as the Le Pen position. After all the Front National wants to abolish dual nationality and force French Africans and Arabs to choose (at least until they can be deported back to their ancestral lands) whether they are really French or not. Make no mistake about it: the FN is still fighting for an ethnically pure France, whether Le Pen admits it or not.

Down with the centre!

It still looks like the battle will be between Melenchon, Le Pen and Macron. Faced with this three-way split, the French electorate has a real choice for perhaps the first time in decades. The hope of Melenchon supporters is that Macron can be knocked out in the first round. If Melenchon and Le Pen both make it to the second round, the French may just get to make the kind of decision which was denied to the American people in 2016.

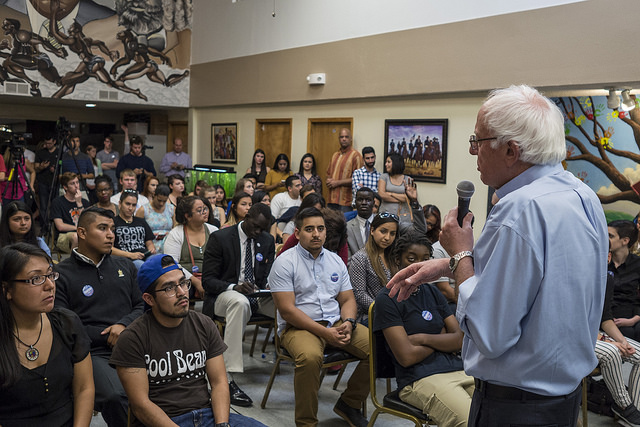

It could be the battle of outsiders that should have taken place between Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Yet liberal centrists placed their bets on Emmanuel Macron and the alleged ‘safeness’ of his candidacy. Many American liberals believed the same about Hillary Clinton. They thought it was impossible for a self-described socialist to win against a populist outsider. They were so arrogant as to believe Trump could not win, and the flaws of Clinton were dwarfed by his vulgarity.

The French election is even more volatile. At first, it looked like Francois Fillon would be the main challenger to Marine Le Pen, but he has since been blown out of the water by a corruption scandal. The Socialist Party never stood a chance thanks to the unspeakable mediocrity of the Hollande government. Then the party base surprised everyone by picking Hamon. And then Macron emerged as a serious contender.

Suddenly, the liberal commentariat had found its man: a millionaire stockbroker with an astroturfed mass of support. Mainstream European liberal opinion began to coalesce around Macron, as the guy who can save the centre ground and restore the Franco-German compact. The populist zeitgeist could be defeated once and for all. But the possibility that it might be too late escapes their minds.

Almost everywhere you look the centre ground is in crisis. The time for moderation and compromise is not today; there is no gradualist strategy for fending off Le Pen indefinitely. Instead, the only sensible choice is to take the consensus with both hands and throw it to the ground shattering it into a million pieces. It’s only with Melenchon that France and Europe have a chance.

Photograph courtesy of Ministerio de Cultura de la Nacion. Published under a Creative Commons license.