How do you register the passage of time? It’s a question that dominates the new season of Twin Peaks. This was probably inevitable, once Mark Frost and David Lynch decided to bring back members of the original cast over twenty-five years later. But their decision to confront the strangeness of this return head-on has made it resonate with a bracing profundity.

Like so many fans of the television series Twin Peaks, I initially found the news that a third season was in the works both thrilling and terrifying. The show mattered a great deal to me when it first aired and has only grown in importance during the intervening years, as I rewatched it many times over, first on videotapes recorded at home, then on DVD, Netflix and Blu-Ray. The more I burned the original episodes into my brain, the harder it became for me to imagine anything surpassing its peculiar fusion of humor and horror. And I know a lot of people who felt the same way.

No matter how much we loved The X-Files, Six Feet Under or True Detective, not to mention all the other “quality” television series produced in the interim, they were always going to be distinct from that first overwhelming crush, when we couldn’t believe that something so artfully alienating was being broadcast on a mainstream commercial network and, what is more, that it found, at least initially, an audience of like-minded individuals. The search for origins may be a fool’s errand, but it is hard to dispute the fact that Twin Peaks changed many people’s desires and expectations where television is concerned.

That’s why I feared — again, like many other fans — that the third season could do significant damage to the memory of that historical break, retroactively transmuting wonder into disenchantment. Perhaps it still will. But so far, after the first four episodes, I am hopeful that I will end up loving Twin Peaks even more by the end of the summer. Not because it will be able to recreate the magic of 1990, but because the new episodes are unabashedly confronting the impossibility of doing so.

There is still plenty of magic, mind you. It’s just that we are being forced to recognize that it is powerless against the ravages of time. I know that, when I first saw current photos of the original cast members, I was taken aback by how many of them looked substantially older than I would have expected. This was particularly true for those, like Sherilyn Fenn, Sheryl Lee, James Marshall, and Dana Ashbrook, who had played teenagers during the show’s original run. So many actors in Hollywood resort to artificial means of making themselves look much younger than they really are. But in the publicity photos and promotional clips I saw for the forthcoming third season, they looked like they had lived very hard, lacking either the will or the resources to drink from the technological fountain of youth.

Having seen the first four episodes several times now, I am convinced that the showrunners consciously pursued this effect. The way Kyle MacLachlan, now playing three different roles, appears is especially important in this regard, not only because he is the new season’s narrative lynchpin — pun, of course, intended — but because he has been seen pretty consistently over the past decade in Desperate Housewives, How I Met Your Mother and Portlandia. People who have watched these shows will know that he looks older than he did during the first two seasons of Twin Peaks, but also that he has retained most of his rugged good looks. But in the new season, by contrast, he consistently looks wrong in some hard-to-define way, as if the trials the iconic FBI agent Dale Cooper had been suffering while trapped in the Black Lodge revealed themselves in the very musculature of his face.

Maybe some of the other actors from the original show do look so weathered simply because they have experienced real struggles themselves. Most of them did not end up having very successful careers by Hollywood standards. I’m willing to venture, though, that they could have been spruced up a lot more than they were, if the showrunners had wanted them to recapture some of the glamor they exuded while being photographed for one magazine after another during the height of Twin Peaks’ popularity.

It doesn’t help that a high percentage of scenes feature the exaggerated pauses that David Lynch is famous for. When the characters on screen aren’t speaking, viewers naturally scrutinize their faces more closely. Combine that half-speed effect with the overwrought close-ups for which the original show was famous and it is inevitable that the then-and-now aspect of the new season will be accentuated. When Bobby Briggs, now a policeman, is confronted by the iconic photo of his former girlfriend Laura Palmer as the homecoming queen, the fact that his hair is now much shorter and grayer is impossible to overlook. The moment is especially powerful, because Bobby’s reaction is a stand-in for our own: we keep getting older and she stays the same age.

Perhaps David Lynch’s decision — motivated, no doubt, by financial considerations — to shoot the new season digitally, as opposed to with the 35mm film used for the original run, is also a factor in the deglamorization of his characters. The overall visual aesthetic is definitely harsher and less forgiving. But I’m pretty sure that he could have managed a softer, more flattering treatment of faces in spite of those technological limitations. It’s as though the ugliness that Cooper’s investigations helped to unearth had traded places with the simple pleasures he marveled at upon first arriving in the town of Twin Peaks.

That is the plot point from which the new season starts. In the first two episodes, Cooper is still trapped in the Black Lodge. And his doppelgänger is running rampant. Presumably, as the new season unfolds, we will get a better sense of whether it is even possible or desirable to traverse the passage between our world and the world of Twin Peaks still. I get the sense that Mark Frost and David Lynch, for all the effort they put into this venture — Lynch directed every episode this time — aren’t sure themselves.

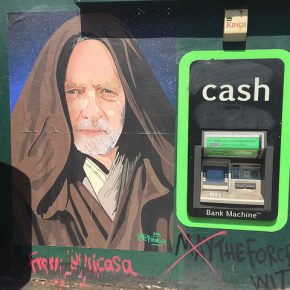

We live at a time when popular culture has become overwhelmingly nostalgic. Sometimes this trend inspires attempts to recreate the magic of old favorites, whether through sequels like Finding Dory, full-on reboots, like the J.J. Abrams-helmed Star Trek and Star Wars films, or brash recontextualizations, like Riverdale’s wry take on the relationships depicted in decades of Archie comics. And sometimes it leads, instead, to reissues of those old favorites themselves, frequently amplified by the release of previously unavailable content, whether in the form of rough drafts, fragments or artfully reassembled “director’s cuts.”

For someone who has been around for a while and still wants to try something new, the relentless pressure to turn your face towards the past instead of the future can be deeply frustrating. David Lynch seems like a fairly well-adjusted fellow, content to work on his paintings and leave navigating the restructured film industry to younger, hungrier individuals. Yet his career has been filled with disappointments, from losing control over Dune, to being forced to reveal Laura Palmer’s killer in the second season of Twin Peaks before he was ready to do so, to having to cobble together feature films in Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire from ideas that were meant to be stretched out to the length of a television mini-series.

Now, finally, in what might be his last filmmaking project, Lynch was finally able to secure the measure of control he had long pursued, but only because the original Twin Peaks made a big enough impact to make nostalgia commercially viable. I mean, Eraserhead was a landmark movie and a cult classic, but there was never a chance of a television network giving him carte blanche to revisit its world at length, even in an era when there are more series being made than ever before. In order to operate the way he wanted, you might say, Lynch simply had to return to the Black Lodge.

And I, along with many other fans of Twin Peaks, am deeply grateful. But I think it’s turning out to his and Mark Frost’s great credit that this gratitude is being adulterated with ample doses of anxiety and disgust. To look at the original cast members as they are presented to us in this new season is to be confronted with one’s own mortality, the realization that, no matter how badly we would like to return to their younger, more beautiful selves or, more pressingly, our own, the pursuit of this desire is bound to be complicated and painful.

I cheered when Agent Cooper finally made it out of the Black Lodge in the third episode, after a harrowing sequence that matches anything David Lynch has done in its disquieting surrealism. When he found the key in the pocket of his black Men In Black suit jacket to room 315 at the Great Northern Hotel and then survived a hitman’s ambush because he bent down to pick it up off the floor of the jeep in which he was riding, I hoped, for a minute, that the old Coop would suddenly spring to life, as clear-eyed and cheerful as ever.

Upon further reflection, though, I’m glad things didn’t prove so simple. The near-autistic man stumbling around a tawdry Las Vegas casino winning jackpots without having the wits to celebrate his good fortune is hard to watch, especially if you remember the man he used to be. Somehow, though, I think that is exactly the effect the showrunners were after. They want us to understand that, for all of his confusion, he still seeks, as he mechanically repeats in the fourth episode, a place he can call “home”. It just might not be the one that any of us are nostalgic for. And that, in an age when everything that promotes caring and decency in the world seems to be in jeopardy — indeed, when the very planet we call home is in dire peril — seems like the sort of message we need to ponder. That lovely waterfall may still be there in the show’s opening credits, but this time it feels like we are plummeting over the edge.

Photographs courtesy of the author. All rights reserved.