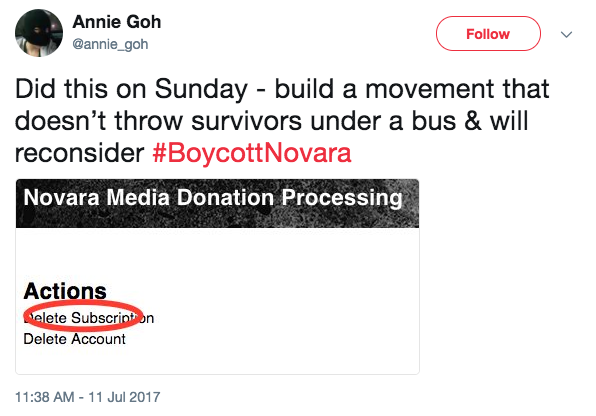

It’s clear from the #BoycottNovara controversy that “callouts,” which have become popular in feminist and anarchist circles, need to be reexamined. Increasingly, callout culture has become synonymous with social media mobbing, boycotts, abusive e-mails, and shunning, now being aimed at Novara Media editors.

Often, these responses make it more difficult to deal with offensive behaviour, and issues of safety, in avowedly leftist groups and community spaces.

The problem is communal tendencies towards groupthink, which quickly lead to scapegoating, and the use of circular logic, accompanied by a ‘culture of silence’ over what may or may not have happened. Ultimately, such behaviour makes it very difficult to talk about what the actual problem is.

These situations tend to follow a basic format. First, there is a callout by someone, who either says that they are a survivor of X’s behaviour, or that they heard about it second hand.

When it’s the latter case, the person often can’t or decides not to divulge who they heard the allegation from.

Friends of the person who say they’re a survivor, or those supporting them more generally, don’t ask for additional details, because they don’t want to traumatise them further.

The logic is perfectly understandable, but social communities tend to collapse gossip into a single charge that they then circulate as though it were the truth.

One of the biggest problems in callout culture is the echo chamber effect of social media. Whereas in a previous era, X may have been called out in private, a callout is now likely to circulate on Facebook or Twitter. Within a few hours, hundreds of people around the world might have seen and discussed a libellous charge they may have little to no relationship with.

Grimly, as more people join in, they will respond to the lack of information about what X did by sharing their own traumatic experiences to help frame the situation. The result is that X has no recourse to discuss or defend themselves from charges. Guilty or not, they discover that their alleged conduct is enabling wider community discussions about unethical behaviour.

The only solution to such situations is for community members to talk to the alleged offender about what they’ve done wrong, and help them come to terms with it, while also acknowledging that public discussion of their behaviour is not always helpful. This is the real work of accountability and “transformative justice” that leftists and activists like to speak of, and it tends to be heavily gendered.

Callouts do not need to be abandoned completely. It is important that in the context of organising, people feel empowered to express themselves, and that those problems are discussed with a positive solution in mind. But there needs to be a balance.

Callouts need to be followed up by calm responses that involve getting information, without being intrusive, and responding in a manner that is appropriate for the situation. It is clear that the #BoycottNovara issue, for example, could have been handled far more productively, and did not need to develop into a boycott and public smackdown this quickly. This isn’t just for the benefit of the involved parties. Often, people will not come forward about their negative experiences because of a potentially intense collective reaction, making it important to both take these matters seriously, and deal with things in proportion.

Unfortunately, if issues with callouts are not dealt with, the dynamic will continue to be one of punitive responses that are far too public, unclear, and end up impeding discussion of serious problems like racist and sexist violence, and eroding the kind of community trust that is desperately needed for long-term political organising.