I loathe seeing people in handcuffs. It is a common enough experience, yet not one that I witnessed until mature adulthood. There is a deep offense to the sight of people in handcuffs or leg-chains, worse than imprisonment.

With handcuffs the deprivation of liberty is immediate and inflicted directly upon a body. The result is a sense of shame at an assault against a common humanity. Sometimes they may be necessary, but they are always ugly.

A couple years ago I watched a prisoner standing at the portal of Florence State Prison where I teach. He was a bald middle-aged white man who appeared broken and prematurely old. He stood, shoulders sagging, handcuffed and with leg chains. He was a sad sight. No one paid attention and he remained standing in the sun, resigned. I silently commiserated with him. His crime was history; this was a moment of suffering. Yet the pity one feels is insufficient: someone who has never worn handcuffs feels this emotion.

Inside an Arizona prison, it is a liberalizing regime when officers no longer escort students to class in handcuffs where they spend the class period uncuffed, each in a separate steel cage, but instead only handcuff students to their desks. Prisons normalize the sight of handcuffs and leg restraints. I am familiar but not inured, not in the least.

The moment I realized the depth of my feelings about handcuffs came years ago. I was an IDF infantry reservist serving on a tank base. It was there I received my sole military command leading a squad of ten soldiers responsible for bathroom cleaning, gardening, and guard duty. One day outside the base commander’s office he introduced me to a regular-service soldier named Moshe. “He’s being assigned to you for a couple weeks until he leaves us,” the officer said. Moshe was waiting for the military police to pick him up in order to begin a six-month prison term for desertion. He had passed six arduous months of Golani infantry training. Instead of joining the brigade, after prison he would return to a non-combat unit to finish his mandatory service.

Moshe was a good fellow, a hard worker, and cheerful. I enjoyed his company. One day he came into the commander’s duty office during a break and saw me sitting at a long table writing in my journal. He asked permission, looked at the mostly-full book, and asked, “Why do you write so much?”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JXdg8MZlHPw

I answered, “I have a lot of thoughts. There is whole row of these at home.” He shook his head at the thought. “Now let me ask you a question,” I said. “You were in Golani and made it through training. Most do not. Then you deserted for a couple weeks. Why did you throw it all away?”

The base commander had been sitting there quietly behind his desk and looked up, interested in whatever answer came. Moshe shrugged, “I don’t know.” There was no answer he cared to share. A half-hour later two military police arrived at the office, handcuffed Moshe’s hands in front, and were about to lead him away. I turned my head away, not wanting to watch. Then Moshe leaned over the table and shook his cuffed hands angrily in my face. “Look! This is what they do!”

It was a call to witness, not to turn and refuse to watch. Possibly at a deeper level that also was the answer to my question. The gesture and words related to much more than the immediate moment. The MPs led him away and that was the last we saw of him.

Watching the confinement of fellow humans is one form of difficulty, but those doing the handcuffing and imposing restraint have an emotional reaction equally. Police, sheriffs, and prison officers train in the practices of restraint, but do they ever truly normalize the act? Learning about levels of control, physical resistance, positioning subjects, and safe technique attempt to neutralize an emotional act. Training provides a professional veneer, not competence in the emotional labor involved. Or, if those applying handcuffs enjoy their work, are they the sort of people to whom it is a good idea to give authority?

There is a ritualistic quality to applying handcuffs, as if preparing a prospective victim for human sacrifice. The ritual is one of submission that if resisted can turn deadly violent, as happened in 2014 when Eric Garner resisted handcuffs and died from a chokehold.

In the context of US history, the physicality of handcuffing, waist chains, and leg irons evokes the images of race slavery and transport from Africa. There remains an undeniable symbolism to handcuffing people of color, a repetition of traumatic history. Witness of handcuffs functions demands a social level as much as at an individual one.

Restraint of wrists and arms operates as part of a continuum of systemic and physical violence that has had harsh historic consequences for people of color and working-class people in the United States. When in Melville’s White-Jacket the old sailor Ushant stands on the Neversink’s deck in irons for refusing to shave his beard, he represents working-people who refused social conformity or state discipline and suffered the consequences. A defeated Black Hawk wore a ball-and-chain in a Missouri prison barracks in 1832, a symbol of colonial dispossession. Edward Isham, a poor and violent logger and miner from Georgia, wore handcuffs as he dictated his murder confession and then suffered hanging in 1860.

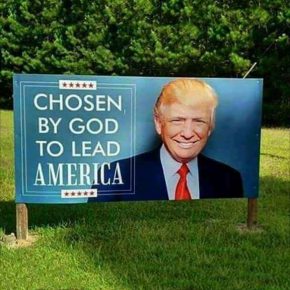

Nineteenth-century histories of restraint continue into the twenty-first. Perp walks with a handcuffed prisoner have become one of America’s favorite news scenes. We treat politics as a perp walk too: “Lock her up, lock her up!” cries still greet Trump’s denunciations of Hillary Clinton. American politics are filled with calls for arrest and cuffing. Everyone suits a pair of handcuffs. A country that conceives of itself as the embodiment of freedom has an antithetical passion for locking wrists together.

According to most recent data there are over 11.2 million police arrests annually in the United States, with a heavy disproportion of blacks and Hispanics. This makes handcuffing one of the most common forms of government interaction with citizens, not to mention over a half-million non-citizens arrested for immigration violations. There are no good national data on the number of juvenile arrests but it can be estimated in the millions. Schools have become the sites of mass handcuffing with tens of thousands of reported arrests annually by euphemistically-termed school resource officers.

Handcuffs are only a stage in a larger process of mass arrests and mass incarceration. Using an associated police technique as a social metaphor, Paul Butler wrote in his recent Chokehold: Policing Black Men, “A chokehold is a process of coercing submission that is self-reinforcing. A chokehold justifies additional pressure on the body because the body does not come into compliance, but the body cannot come into compliance because of the vise grip that is on it. That is the black experience in the United States. This is how the process of law and order pushes African American men into the criminal justice system.” Butler continues forward to suggest that this same chokehold metaphor to characterize discriminatory police treatment against other minorities, including Hispanics and Moslems.

Handcuffs and chokeholds are the business end of social force that creates civil obedience. Like many, I have a special admiration for congressional representative John Lewis who has been arrested several dozen times and who is known for making jokes whenever he is being handcuffed for a new act of civil disobedience. Yet the implicit question that arises when watching arrests of social justice activists such as Lewis and other handcuff habitués is ‘Why are you only watching? Why have you not been arrested too?’ One way or another, the sight of a handcuffed human indicts the conscience.

It would be naïve or utopian to believe handcuffs have no appropriate uses, or that restraint is not necessary, or there are no legitimate safety rationales. Questioning the use of handcuffs and resistance to their normalization responds to that challenge – “Look! This is what they do!”

Photograph courtesy of zeeveez. Published under a Creative Commons license.