Since the snap election UKIP has entered a new terrain of wilderness. Not only does the party lack its raison d’être, it lacks leadership and a message. No longer do we hear UKIP described as “the fourth party” of British politics.

It’s a year after the June 23rd referendum produced a Leave victory and UKIP has yet to find stable leadership with a clear agenda for the new era. Yet Nigel Farage stepped down just after the vote. He probably understood that the opportunity to resign on a high note is extremely rare in political life. But the party was left rudderless.

What this means for UK politics is crucial. Farage helped reshape the national debate on immigration and the EU. He did so by relentlessly fighting against the liberal consensus of Europeanism, open borders and free trade. What happens to UKIP now could be a sign of the challenges we face in years to come.

The Farage legacy

Once Brexit was on the table, UKIP ceased to offer an alternative to the liberal consensus because the centre ground was effectively fractured. The right-wing party had driven a wedge through the Conservatives and Labour to the core of this consensus. Yet these gains could not be sustained.

The best thing for UKIP would have been a narrow victory for Remain. Farage would have gone down claiming that the ballots had been ‘rigged’ by postal votes. The right-wing vote could have been consolidated into a bloc to rival to the Conservative base. This would have guaranteed UKIP a place on the right for years to come.

Instead, the party was left to redefine its agenda. After months of chaos and infighting Paul Nuttall came to the helm pledging a new offensive on Labour heartlands, where they would claim the ‘white’ working class for themselves. It never happened. Fortunately, Nuttall was stupid enough to believe what Farage knew was rhetoric. This led UKIP down the path to humiliation in 2015.

Nuttall was dead meat after losing the Stoke by-election. He stood again in Skegness, but it was a lost cause. UKIP might have thought it could have stood in a chance in a Tory area, where it could eat into the right-wing vote. But the moment had passed. There was no reason to vote UKIP in Skeggie a year after the referendum.

Some of us saw through the narrative that the UK Independence Party was a threat to safe Labour seats in the North and the Midlands. That’s because some of us have lived outside London and have loved-ones in these places. Real people with accents you don’t hear on Radio 4.

Without Farage, UKIP has failed to build on the remarkable gains of the 2015 general election. With Farage won almost 4 million votes and failed to win any seats (even the one UKIP seat held by that point was secured by defection). He left behind a power vacuum when he gave up the leadership.

Rebuilding the far-right

Now UKIP still faces the difficult task of redefining itself and finding a new leadership. The coalition of right-wing libertarians, traditional conservatives and nationalists may have to be divided for this end to be achieved. The multi-class character of the vote has already changed. Arguably, Labour and the Tories have reclaimed their old voters.

One option is for the party to run down the road of free-market fundamentalism. The libertarian tendency has always been strong in the party’s ranks, yet the problem of how to sell it to the public remains. There is very little appetite for untrammelled market forces and cold-hearted individualism.

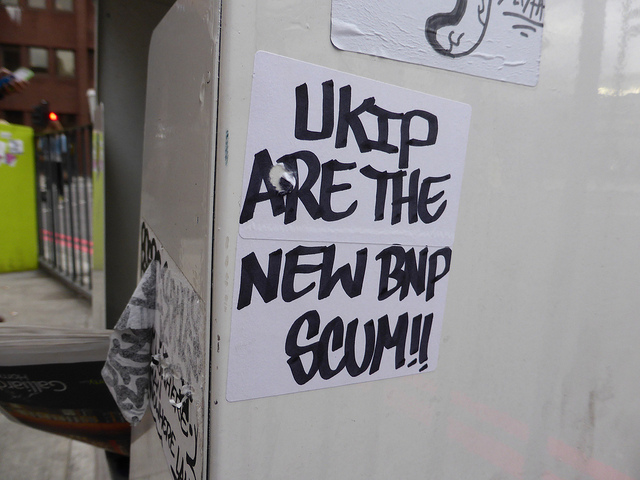

The alternative is an openly nationalist campaign with no ambiguity about its new target: Muslims and Islam itself. This is where Anne Marie Waters has positioned herself. The party has been swarmed by hundreds of traditional far-right activists from groups like Liberty GB, the BNP and the English Defence League.

For example, Jack Bucky is working to support the Waters leadership campaign. A youthful right-wing activist, Buckby is a former member of the BNP and Liberty GB. He also stood in the constituency of Jo Cox, the Labour MP brutally murdered during the referendum campaign.

Whereas UKIP always used to be a coalition of disaffected Tories, libertarians and nationalists, the British far-right has not been afraid of Nazi salutes. The possibility of a nationalist takeover can’t be ruled out, but it’s unclear what its success will mean. One possibility is that UKIP becomes the mainstream party of Islamophobia (as if this weren’t already mainstream enough).

On the other hand, UKIP could just become another group in the fragmented world of the extreme right. It would quickly face new scandals and difficult questions, as the media’s scrutiny would be turned on Waters and her supporters. There will be plenty of dirt to be turned over and thrown back at them.

What could reverse UKIP’s chances at this point? If the UK didn’t leave the EU and the party somehow retained a saleable image and charismatic leader, the future might be brighter. But there is another possibility. If Brexit turns out to be a disaster and the far-right could picks up the fallout. Nothing is certain at this point.

Photograph courtesy of duncan c. Published under a Creative Commons license.