We live in confining times. Prison narratives proliferate and disappear quickly. Yet only the occasional narrative, such as Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s Guantánamo Diary (2015), receives sustained attention and then due to its obvious political import. Prison writing is difficult because it forces a double confrontation, both with state and self.

There is a special problem facing imprisoned writers in long-term solitary confinement. Sitting in a small, tight, and most often windowless space, deprived of sensory stimulation and social company, what does one write about?

Telling stories of long-term solitary confinement, beyond descriptions of immediate conditions, can be difficult. This is not the romantic world of Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo with Edmond Dantès in the Château d’If transforming himself through education.

The solution that many writers in solitary discover, such as Wole Soyinka in his astonishing but too-little-read prison account The Man Died (1971), is to escape into memory for as long as possible. The immediate fades; the past dominates consciousness; possible futures remain tentative. Similar characteristics are visible throughout much prison writing, but they intensify in solitary confinement.

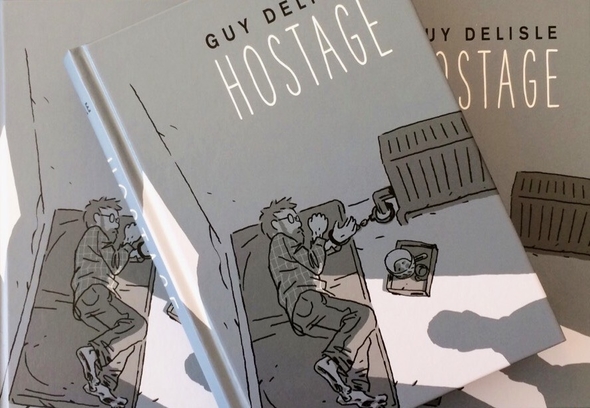

Hostage, a massive 432-page new work from the well-known artist Guy Delisle, narrates the solitary confinement of Christophe André, a Médecins sans Frontières official kidnapped in Chechnya in 1997. The graphic literature of solitary confinement is even more limited than the thin canon of textual narratives, so Delisle is rather lonely in this endeavor. That is unfortunate, since graphic literature, with its figuration of body and faces, has a great deal to contribute towards exploring the emotional and sensory deprivation experienced in solitary imprisonment.

The power of Delisle’s work lies in its attention to the detail of what might otherwise seem a monotonous scene of a man handcuffed to a radiator for what seem unending weeks. Delisle attends not only to small variations in daily routine but also to André’s mental state. The delivery of meals and brief visits to a bathroom become points at which the world gains shape and possibility. André hears family life behind walls and wonders how so many people live there with knowledge that a prisoner lies next to them in a hot, dark room.

Delisle reportedly handcuffed himself to a radiator in a similar situation to understand the limited variety of positions and perspectives possible. Every vertex in the room finds realization repeatedly in the drawings. A bare hanging light-bulb, the ceiling, the walls, and the radiator all become major characters in the story. The dull gray-scale and dark coloring that continues throughout the book emphasizes the dim, close quarters in which this captivity occurred. The gray, black and white cover image of a handcuffed bearded man lying on a mattress reinforces this somber mood. Sometimes Delisle uses progressive darkening over a page or more to indicate André’s darkening mood as he awaits ransom and freedom. In the frames and pages where full light reappears there is a sense of relief, one shared by prisoner and reader.

As André loses track of time in the darkness he begins to build his own fantasy world. He recreates the tactical details of Napoleonic and U.S. Civil War battles as a mental distraction that helps maintain sanity. A sense of unreality pervades at certain moments. Hearing the traffic outside, André thinks, “It’s so unreal to think that life outside continues, banal as ever, while I’m locked up in here, handcuffed to the ground.” Though André is isolated and disconnected, it is memory that provides company. There are striking similarities to Wole Soyinka’s The Man Died, his account of solitary confinement during the Biafran conflict, and Soyinka’s extended mental retreats into his own imaginative consciousness.

What the story finally centers on is André as a competent and self-preserving actor, not one whose fate his hostage-takers will determine. Chechen gangsters kidnap and deprive him of liberty, demand a million dollar ransom from his employers, and leave him isolated without a common language. André becomes a commodity whose value is under negotiation. As Delisle re-narrates the story, André overcomes his fears and relies on his own abilities. He thinks “I just wish that I could get out of here on my own” but the important part is that he acts when an opportunity to escape arises.

After nearly four months, at 111 days, André takes advantage of a lax guard and unlocked wrist to escape. Delisle does marvelous work in recreating André’s moments of indecision and then his creeping through an empty house into the dark and cold. This passage, filled with staccato internal thought balloons, carries intense suspense due to Deslisle’s masterful combination of artwork and text. It provides culmination for a liberation process that is first mental and then physical, following a classic pattern in self-emancipation narratives.

Shivering from the cold, with bloodied feet, André manages to catch a bus where a young Chechen befriends him and brings him home to a village near Grozny where André begins to recover from his ordeal. André’s employers arrange transport out of Chechnya and whisk him off to Moscow on his way back to Paris. The final page-wide frame of the book features André standing in the Russian countryside enjoying what he has missed for so long, an open horizon. An after-note informs readers that the Chechen family that harbored André endured death threats from his captors; they fled the country to France, which granted them asylum.

Helge Dascher’s translation from French is crisp and effective. Dascher has developed a specialty in translating comics and her experience is visible. Delisle has become known for his work in graphic travelogues after visiting North Korea, China, Burma, and Jerusalem.

At its surface, Hostage tells a story of foreign travel gone desperately wrong. What emerges is another story, one of imprisonment and survival of solitary conditions. Yet André had an international aid organization working to obtain his freedom. In the United States there are well over 80,000 people in solitary or isolated confinement of different sorts, a system whose debilitating psychological effects are well-known. The question is who will work to end their confinement?

Images courtesy of Drawn & Quarterly. All rights reserved.