The reactions were predictable. Putin perfunctorily denied it was an invasion, while the media wondered whether it was even right to even call it a war. That Russian forces were already occupying a third of Ukraine was still insufficient evidence. Nearly 15 years from the day when he first too took the reins of the presidency, the ex-KGB agent was living out the wildest of Cold War fantasies, about Russian politics, and its hackneyed intrigues. Dr Strangelove would have approved.

One of the first decisions undertaken by Putin after the 2000 election was to restore the Soviet National Anthem by Alexander Alexandrov. It was a symbolic break with the Yeltsin era. The anthem replaced the Patriotic Song of Mikhail Glinka that the Russian Federation had adopted in the wake of the dissolution of the USSR. Many in the West perceived this as an ominous sign of things to come. As the 1996 election was deemed to be the last hope for Russia’s Communists, the alternative to Yeltsin had always been framed as a throwback to the days of Stalin.

The return of Alexandrov’s anthem seemed to confirm Putin was looking to recreate the old Soviet Union. This perception was widely shared, particularly by free market advocates, fearful that their revolution was coming to and end. Leading liberal Grigory Yavlinsky said, “We see this as a signal of where our society is heading, of what awaits us in the near future”. Yavlinsky was a proponent of the 500 Day Programme, first articulated in the late 1980s. It called for the mass-privatisation of state assets combined, with market reforms and the stripping away of regulations. All in 500 days. The programme was eventually implemented, in diluted form, under Yeltsin.

What was lost on market liberals like Yavlinsky was that it wasn’t just about economics. The Soviet anthem has an equally significant nationalist side to it. After all it comes from Stalin’s Great Patriotic War, and supplanted the traditional socialist anthem the Internationale with its revolutionary patriotism. It was this side of the Russian campaign that Putin was tapping into, not a retreat back to the state capitalism of the Communist era.

It’s necessary to keep in mind that the war in Chechnya was still fully ablaze in 2000. Putin probably thought the white heat of chauvinism would be best harnessed at this time. It took nearly a decade to quash the Chechen rebellion, and in that time Putin built up an assertive state recuperating from the economic turmoil of the transition to the free market. That was what mattered most to him at the time, and plays as important a role in his self-definition as the recovery of Stalinist totalitarianism, and its revolutionary imagery.

Fighting Fascism

Putin isn’t just an ideologue, however, for whatever mix of post-democratic politics he’s pushing. He also knows how to push the buttons of the Russian people, and work their sense of history. Most particularly the legacy of the Second World War, and the sense of loss, and grievance, it continues to instill in Russians, to this day. If the West wants to understand why Putin’s repeated invocation of Nazis and Fascism, and his attacks on NATO have helped mobilize such strong support for his actions in Ukraine, a little history goes a long way.

Over 20 million Russians died in the fight for the Soviet Union’s survival against the onslaught of Hitler’s Third Reich. The invasion came in June of 1941. By October, German troops were at the outskirts of Moscow. It wasn’t until January 1942 that the Russians repelled Nazi forces. In total, the Red army would confront 200 Nazi divisions and defeat the Germans in the battle of Stalingrad, and the siege of Leningrad, where millions were killed.

It didn’t have to be this way. The Third Reich could have been defeated by a two-front assault much earlier. Out of fear of a German invasion, Stalin had attempted to foster an alliance with Great Britain and the United States in the 1930s, before sending Molotov to cut a deal with Hitler. It was the last resort of a regime fearing the potential of German aggression. Stalin ignored all advice and believed Hitler would not invade. He fell into despair once the Germans swarmed into the USSR looking to exterminate ‘Judeo-Bolshevism’. The invasion looked like the beginning of the end.

At the same time, the Soviet war machine was not to be romanticised. It was a brutalising system as Stalin implemented the “Not one step back!” order – any retreat was punishable by death. The regime had been run on a suicidal logic since the 1920s as Stalin had his enemies, both real and imaginary. All in all, Stalin is said to have killed more Communists than Hitler. Officially 3 million people died in the gulags alone, though the true figures are thought to be much higher. Only a few days ago, the remains of up to a thousand people (mostly Polish) were unearthed in a mass-grave. It’s thought that the NKVD gunned them down.

However, it must be made clear that there is a subtle distinction to be maintained. There is a qualitative and quantitative difference between the crimes committed in the Soviet Union and those committed by Nazi Germany. Not only did Hitler set off a chain of events, which slaughtered more than 60 million people, in just a few years. The Nazi plan for Eurasia amounted to the systematic annihilation of European Jewry first, then the same for 30 million Slavs, and then the deportation of 30 million more Slavs into eastern Russia.

Taking the fight to NATO

The pointless bloodbath of 1914 created the conditions needed for the Bolsheviks to triumph in Russia over Tsarism. In the defeat of Germany, it eventually led to the rise of National Socialism. Once the cycle of mayhem had started, it was not possible to turn back. Had Lenin and Trotsky lost the civil war, the outcome would have been a proto-fascist regime set up by the White army. The absolute worst case scenario would have been for fascism to arise in Russia, and then spread throughout Europe because it could only be defeated on two fronts. It doesn’t require any sympathy with Stalin’s abattoir socialism to see that the Soviet Union was a necessary entity in the war against Hitler.

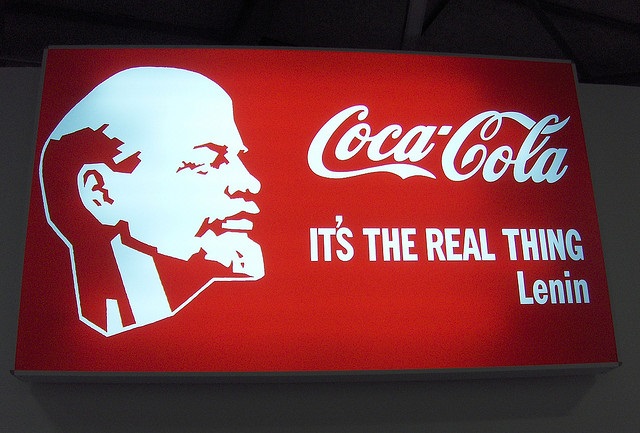

It has been suggested that the world situation didn’t come full circle until 1989 when the Berlin Wall was brought down by the German masses. Soon Russia would be one nation under Yeltsin and Germany would be reunified, once again. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that Putin comes at the end of this story. Only after the Soviet system is completely gone can the competing mythologies of Communism and Tsarism re-emerge as moments in a nationalist narrative. Only Putin can deploy the imperial notion of Novorossiya, as his troops march to Alexandrov’s tune.

Once Crimea had re-joined Russia, by way of invasion, Putin attended Victory Day commemorations of the seventieth anniversary since the Crimea Offensive against the Axis Powers. He came to Sevastopol, where tens of thousands of Crimeans are said to have chanted “Russia!” as a thousand troops, sixty military vehicles, thousands of veterans and other groups marched past. The conflict within Ukraine received a new historic frame. Crimea had been ‘liberated’ from the fascists who overthrew Yanukovich in Kiev.

Not only that, but the conflict, predictably, now with NATO, became the fight for Russian greatness in a new century. The fact that NATO was founded to secure Europe from hypothetical Soviet aggression in 1949 meant that the alliance had no purpose after the Soviet Union collapsed. NATO should not have expanded further. It should have been disbanded after the Cold War. As much as this hostile military alliance stands as a nightmare from another era, the chauvinist forces mobilising in Russia match it in that sense. Aptly, Leon Trotsky described Russian nationalism as the “messianism of backwardness.”

Photographs courtesy of Amy Ross, darius norvilas, and Caspar Hübinger. Published under a Creative Commons License.