These are uncertain times in the US. Although the economy has been doing better, most people still seem to feel that it isn’t doing better for them. A state of half-war continues to prevail internationally. And reports of brutality by both local police forces and the CIA have many Americans wondering where their country went.

Admittedly, the present unrest pales still before the turmoil of the late 1960s and the terror spread by the Red Scares following World War I and II. Nor does it compare to the depressions in the late 1830s, the early 1890s or the 1930s. Indeed, there is a good chance that the protests that have disrupted major cities and the public acts of introspection that have come in the wake of the report on torture at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp will no longer be headline-worthy by New Year’s Day. Nevertheless, the sense that major and possibly irreparable damage has been done to the nation’s self-image remains strong.

Even as history books, first in college and then in high school, started to acknowledge black marks on the United States’ record in the early 1970s and the proliferation of media made it harder and harder to profess ignorance of current problems like the Vietnam War or Watergate, a counter-narrative started to gain traction. Maybe we hadn’t been as blameless as the propaganda of earlier eras suggested, but we were still making steady progress, despite backsliding now and then, towards the goals set by our Founding Fathers.

Blacks still had it worse than whites, but they were beginning to close the gap. Women might not have been able to get equality included in the Constitution, but there was no denying that they had more freedom and power than their mothers and grandmothers. Workers had to contend with foreign competition and the difficulty of balancing rights with competitiveness, but they had more robust legal recourse when they experienced individual discrimination or undo risk.

In recent years, the emphasis in this counter-narrative has shifted to the expansion of personal choice in marriage, education and medicine. Things that would have been inconceivable under President Clinton, much less President Nixon, such as gays and lesbians being permitted to wed in traditionally conservative states like Oklahoma and Arizona or marijuana becoming legal for personal medical and, in two states, recreational use are now taken for granted by a majority of Americans.

For some, the availability of information and products on the internet has also seemed to signal a step forward. The massive discrepancies between highly educated metropolitan areas like Boston, San Francisco and Austin and the vast hinterland that still comprises most of the United States have been steadily diminishing as rural and suburban consumers are able to access an astonishing wealth of material without leaving their homes.

To those Americans who want desperately to believe that the nation is still in the process of realizing its special destiny, serving as a beacon to people all over the world who desire self-determination above all else, these developments are ritually exhibited as proof. And when compared to places like China or Russia, where democracy is truly an illusion, or the Middle East, India or Japan, where tradition still inhibits personal growth in various ways, there does seem to be validity to their argument.

Unfortunately, however, the attention being drawn to the inconsistent execution of the United States’ laws is undermining it at a rapid pace. Ever since the Patriot Act was formulated and ratified in the weeks following the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001, Cassandra figures have been warning that suspending the rules of peacetime indefinitely would have a corrosive effect on the nation’s image, both as perceived abroad and felt at home. Now that more and more evidence has come to light of just how far the government will go, from Chelsea Manning, Edward Snowden and now the Senate’s own report on the use of terror, it has become difficult to determine whether the country’s much-vaunted system of checks and balances remains relevant.

All of the progress that had been made in the aftermath of Watergate towards greater transparency, powerfully enhanced by widespread use of the internet, is now in jeopardy. Even if citizens have unprecedented access to much of what their government does in its official capacity, the existence of a second, “shadow” state can make their potential to be well informed irrelevant. The convoluted legal maneuvering which not only confirmed that the Guantánamo Bay complex was outside of U.S. jurisdiction, but essentially made it possible for any place to be treated that way under exceptional circumstances gave the Executive Branch a degree of power which the Constitution was explicitly devised to prevent.

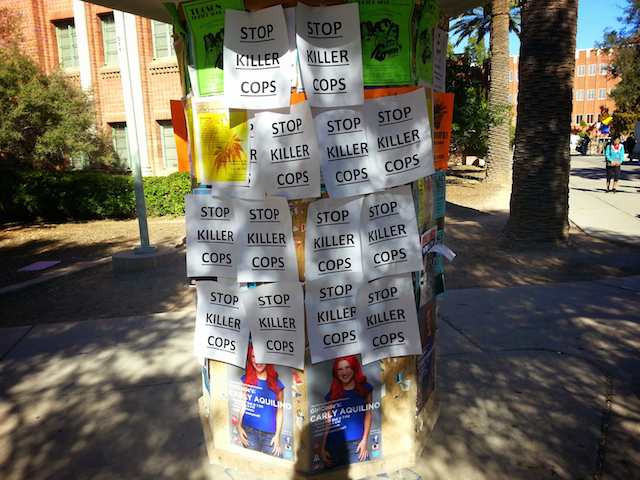

Parallel to these challenges to the rule of law have been a well-documented expansion of local police forces’ freedom to act with impunity and technological capability to do so with devastating results. When city and county governments are empowered, under the guise of fighting terrorism, to direct a military level of force at their own citizenry, the longstanding — if ethically hypocritical — distinction between what the United States does “over there” and what it permits back home no longer seems that meaningful.

It is worth recalling here that Senator Rand Paul, who is mulling a run for President, framed the death of Eric Garner, not as the result of overzealous policing, but irresponsible taxation. If the state of New York had not decided to defend its high taxes on cigarettes against entrepreneurs, Paul argued, who purchased them elsewhere at lower rates and resold them on the streets to make a profit, then there would have been no need for the police to confront Mr. Garner in the first place.

Paul was widely ridiculed on the Left — or what passes for it in a United States where Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton are called “socialists” — for trying to shift the emphasis away from the immediate issue of police brutality to one of the favorite topics of libertarian thinkers like his father Ron, the burden of taxation. But whatever ulterior motives Senator Paul may have had, he actually did an excellent job of making the sort of connection which Americans have historically struggled to make. Because even if the officer who put Eric Garner in what turned out to be a fatal chokehold acted irresponsibly, the fact remains that he was merely carrying out a policy decision made far away. Yes, he and his fellow officers were the point of visible contact with the state apparatus, but they were merely functionaries in a vast system which uses men and women in uniform to hide the activities of those who wear suits and ties or blazers and skirts to work.

Sometimes, an accident of timing can have a profound impact on public opinion. What is currently being decried as unequal and essentially racist policing is nothing new. Nor should the revelations about what transpired at the Guantánamo Bay detention center come as a surprise, since organizations like Amnesty International have been reporting on the abuses there for over a decade. But the convergence of these two stories and the way in which they have all but blotted out more positive news, at least has the potential to reshape the way Americans think about policing.

What we forget when we direct our ire at police officers or CIA operatives is that, while they may sometimes exceed their mandate, they are mostly just following the orders given them by bosses who answer to other bosses who answer to those elite few whose wealth and power permits them to “boss around” the law itself. Ultimately, police work isn’t just what the men in uniform or their supervisors do. Nor is its international equivalent just what the agents of the CIA or NSA do on the ground. Police work encompasses all the work of the polis, including the sort which goes out of its way to not be seen. If we are serious about curbing the brutality of the state, then, we need to keep the big picture in view. Maybe New York’s tax burden didn’t literally kill Eric Garner, but the state has to share blame for his death.

Photograph courtesy of the author.