Last week, Israelis and Palestinians met in Amman to restart peace talks. Don’t feel bad if you didn’t notice. The event produced nothing. Efforts are continuing, but there is little chance of anything coming of them. It’s merely a show of “getting to the damn table.” In an article in The Forward, Yossi Alpher tries to explain why just “getting to the damn table” isn’t a worthy goal.

Alpher is a serious man, one whom Americans for Peace Now regularly turns to with their “hard questions.” He’s a political realist who does truly pursue a workable peace as he sees it. But his piece in The Forward, intended to demonstrate that there is little hope for progress at this time, ironically demonstrates why we are at such an impasse precisely by misdiagnosing the reasons for it.

Alpher joins the growing cadre of mainstream analysts who are recognizing that the Oslo process was inherently flawed and has finally collapsed under the weight of those flaws. We should all hope that more serious analysts echo his call for “…a new and different peace paradigm.” But he also reflects the liberal, pro-Israel view that sees the problems through a distorted lens.

Alpher gives two reasons for the current impasse, both of which hold a grain of truth but miss the mark in important ways.

Alpher’s first reason is that Oslo “…seeks to sit the state of Israel down at the negotiating table with a non-state liberation organization, the PLO, which represents not just a finite parcel of land aspiring to statehood in the West Bank and Gaza, but also a huge refugee diaspora that wants more.”

Here, Alpher misreads what really is a huge problem with the Oslo process: the disparity of power between Israel and the Palestinians, due to the fact that Israel is not only a regional superpower, but has a “special relationship” with the ostensible broker of a peace agreement that is also the world’s leading military power.

To begin with, there is nothing unusual about a “non-state liberation organization” sitting down with an established state. indeed, in matters of internal conflict, this is the norm, as it was in Ireland, as it is with the Basques in Spain, as it was in Sudan, and many other examples. Any conflict involving the liberation of one people from another is likely to have this configuration.

Alpher is also drawing a false distinction between Palestinians under occupation and those in the diaspora. It is a grave mistake, and a serious misreading of Palestinian society, to believe that Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza are any more willing to forego the return of refugees than their families in the diaspora are.

The problem that Alpher is dancing around is not the multiplicity of layers of Palestinians. The problem is quite simply that Israel does not have sufficient incentive to end its occupation.

Pulling even the limited number of settlements most two-state advocates envision would put a strain on Israel’s political and economic system. The settlement system in general is much more intertwined with the larger Israeli economy than most people realize.

Also, the notion that “everyone knows” the sort of land swaps that would be necessary, which Alpher references elsewhere in his piece, is extremely dubious. Most of Israel assumes that, if they did end the occupation, Israel would retain control of “major settlement blocs” which would include the large and far-flung blocs of Ariel and Ma’ale Adumim which are extremely disruptive to territorial contiguity on the West Bank.

Israel is still flourishing economically, and the threats Israelis feel are from Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas. The fear of ending the occupation is that the West Bank will become another such threat. Thus, whatever anyone else thinks about these threats, Israelis need a reason to risk increasing them, and of throwing their political system (already in considerable disarray) and economy (which is not) into turmoil.

While it’s true that the ongoing occupation and the impasse in talks have increased international disapproval with Israel, most Israelis are not feeling much of an effect from that. Despite the movement to boycott and divest from Israel, Israeli businesses are still doing well internationally, and despite international condemnation, Israel remains part of the major international organizations it has joined.

The limits on the effects of international disapproval all stem from US support. That’s what Alpher might be hinting at, but is loathe to actually state. The United States shields Israel from the effects of its own actions, and as long as that’s the case, there is no hope for a change in Israel’s stances, and, therefore, no hope for negotiations conducted in such an unbalanced atmosphere to succeed.

Alpher’s second reason holds a greater kernel of realism: “The second, related flaw in the Oslo accords is that they lay out a menu of final status issues that mixes post-1967 topics like borders, settlements and security with very different pre-1967 narrative topics like holy places and the right of return of the 1948 refugees. Oslo, in effect, insists that a final-status agreement reach closure on all of them: “Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed” — yet another memorable cliché.”

Alpher gets a bit closer to the mark here. There is a mix of on-the-ground issues with ideological and passionate ones, and that does complicate matters. It is certainly true that if Jerusalem and the refugees can be separated from the territorial and security issues, matters would be greatly simplified.

But that statement sounds bigger than it is. As I explained, the settlement project is not something that is easily halted anymore (for more information on this point, see Akiva Eldar and Idith Zertal’s historical overview, Lords of the Land, and B’Tselem’s reports here, here, and here.)

More to the point, Israel has little enough incentive to end its occupation as it is; the one carrot Israelis do see is that if they do agree to withdraw from Palestinian territory they will do so in exchange for an end of the conflict and an end to Palestinian claims against them. That’s why ordinary Israelis favor the all-or-nothing approach that their leaders use to further stall negotiations.

The Palestinians as well have to be concerned. An Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank would very likely entail a normalization of relations between Israel and the member states of the Arab League. If that happens, they have to wonder why, even with an independent Palestine as an interlocutor, Israel would have any incentive to negotiate on the much more difficult issues of Jerusalem and the refugees.

Alpher is off to a good start in recognizing that the Oslo framework has succumbed to its own flaws. He is right in saying that a new framework is needed. But unless Alpher–and the many liberal Zionists like him who truly do wish to see a just resolution to this conflict — can bring themselves to be honest about what the flaws in Oslo were, the same disease will rot any new vision.

Oslo can offer many lessons and, through them, a guide for what a just resolution that doesn’t depend on some naive vision of Israelis or Palestinians completely changing their national consciousnesses might look like. But only if we’re willing to look at Oslo honestly and critically.

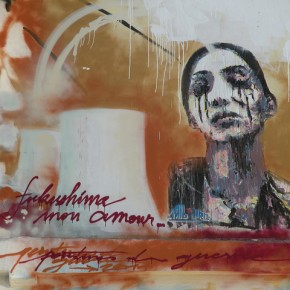

Photograph courtesy of the Israeli Government Press Office. Published under a Creative Commons license.

The comparison to the Basques and Ireland is flawed. Algeria is probably the closest analogy although even in Algeria the integration with France was not remotely as complete as the West Bank is with Israel proper, not to mention the geography.

Since by the prevailing “two nations” discourse Israel is already a bi-national state (because of its 20% Palestinian citizen population), then the only question is whether it’s going to have 20% or 35% Palestinian citizens – that’s what the fighting is all about and that what can possibly usher WWIII – a mere 15%, which is the West Bank’s population of 2 million.

Gaza can be an independent state with open borders since there is no territorial entanglement there.

The refugee issue can be solved with a creative solution that will quell Israel’s irrational fear of refugees (it almost reminds me of someone who fears the ghost of the person he killed will come back to haunt him) by tying quotas of refugees return to Jewish immigration in a way that will not affect the demographic balance. I believe all refugees should have a right of return but this is a pragmatic solution.

And of course, there is quite wide support for the annexation of the West Bank in Israel’s right.