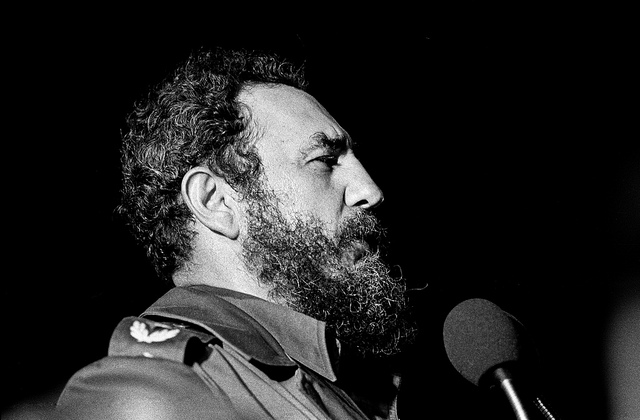

Many people see the death of Fidel Castro as the end of an era. Yet the Castroite legacy is alive in one form. Cuba has played a key role lending support to national liberation movements around the world. One major site of struggle during this period was Southern Africa. There the Cuban leader backed the ANC to the hilt when Nelson Mandela was widely regarded as a ‘terrorist’. Castro opposed European colonialism and fostered ties with independence leaders. This was not simply tactical, it was a part of an emancipatory process.

Contrary to popular misconceptions, the Cuban revolution was really a part of the tide of nationalist struggles against imperialism. Fidel Castro and Che Guevara brought down the Batista regime and threw off the American yoke. But they did not set out to establish just another Soviet-style workers’ republic. Note the ruling party of Cuba was not officially Communist until 1965 several years after the revolution. Much of the symbolism of the Cuban revolution harks back to Cuban patriot Jose Marti.

The truth is Castro seized power thinking he could avoid a direct clash with the United States. Instead the US moved to strangle Cuba almost immediately. Che Guevara sent a box of cigars to John F Kennedy pleading for talks and offering compromise. The Americans smelled weakness. They soon tried to invade the country. The new regime had to either join forces with the Soviet Union or face defeat. This is how Castro went from denying he was a Marxist in 1959 to affirming this position just after the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961.

This same year, the opening shots of resistance were fired in Portuguese Angola. Colonial rule was coming to an end across the African continent, in some places peacefully, in other places the transition was forced from below. Great revolutionary leaders, such as Amilcar Cabral, Agostinho Neto and Samora Machel, were emerging to challenge Portuguese rule. These were the end times for the Salazar regime, but it was not ready to confront its own mortality. Fidel Castro had found a new cause worthy of support.

Under Castro, Cuba aligned itself with the MPLA in Angola and FRELIMO in Mozambique. The independence wars would last until Salazar died and the regime finally collapsed amid the Carnation revolution. Guinea-Bissau was the first to declare itself independent, Angola and Mozambique soon followed. Thanks to the leadership of Amilcar Cabral and the support of Cuba, China and the Soviet Union, Guinea-Bissau and the Cape Verde islands could deliver a fatal blow to Portuguese rule.

Of course, the struggle did not end with independence, a new struggle would soon begin. The MPLA in Angola and FRELIMO in Mozambique would find themselves harassed by new foes. The US and its ally South Africa sided with the FNLA and UNITA in Angola, providing these rebel forces with arms. Meanwhile, the US and South Africa fostered RENAMO to take on Samora Machel. Then in 1975 the South African army invaded Angola. Naturally, the MPLA turned to Cuba for help.

With Cuban back-up, the MPLA defeated the FNLA and South African forces at Quifangondo in November 1975. Incidentally, this was just before Angola declared independence from Portugal. Castro would send over 300,000 Cubans to Angola to provide armed and medical support. Some estimate 10,000 Cubans died in 14 years. As South African forces were crossing over from South-West Africa (present day Namibia), Cuba returned the favour and armed the SWAPO rebels. The war was far from over, and over 500,000 lives would be lost.

South Africa exploited the divisions in Angola and Mozambique, which made them susceptible to civil war. The MPLA credited itself for a broad national appeal, so its opponents draped themselves in tribal and anti-Communist colours. As FRELIMO pursued a socialist line, the pro-capitalist wing of the movement defected to RENAMO. South Africa found support in conservative black governments in Botswana, Malawi and Swaziland. Further afield, Zaire’s dictator Mobutu came to South Africa’s side in Angola.

Fearing for its future, the apartheid regime in South Africa, but also in South-West Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), saw that the challenges they faced at home could not be separated from the end of colonial rule in Angola and Mozambique. The contagion of independence was spreading fast, and it opened a space for the ANC to launch its operations. South Africa began launching raids in neighbouring countries and trying to destabilise independent governments.

Sitting between Mozambique and Zambia, Rhodesia was a major prize and, like apartheid South Africa, it too was fighting a bitter colonial war to defend white rule. Yet US proxies were already bogged down in Mozambique and Angola, it did not want to open a third front in the region. Fearing the reach of Cuban influence, the US began to look for a peaceful settlement to end the bush war. The result was the rise of Robert Mugabe and a new black political class in an independent Zimbabwe.

The US was certainly aware of the dynamics at play. Henry Kissinger backed land reform in Zimbabwe as a means of placating the demands of nationalists. Even still, the defeat of apartheid in Rhodesia was the first sign the days may be numbered for the South African regime. Nevertheless, South-West Africa remained under white-minority rule. The independence of Namibia was the key to bringing down apartheid. It was the last buffer-state for South Africa to hide behind.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DA4VW_FtMZE

The finale came in 1988 at Cuito Cuanavale, where an army of colour composed of Angolan and Cuban troops held their own against the South African army and UNITA in an impressive feat. As this decisive battle took place by the Namibian border, the implications were huge. South Africa agreed to withdraw from Angola, as did Cuba, the UN Security Council passed motions supporting Namibian independence. While both sides declared victory, the myth of white superiority died at Cuito Cuanavale. This was the death knell for apartheid.

Matched by the internal struggle against apartheid, South Africa began to move towards democracy. In 1990, Nelson Mandela walked from prison a free man. He was out in time to watch Namibia become an independent state. Negotiations would soon follow and serious compromises were reached. The 1992 referendum was held in which 68% of white South Africans voted for a new constitution and, effectively, the end of apartheid. This was the beginning of a democratic opening, which would bring Mandela and the ANC to power.

The freedom struggle cannot be reduced to Cuban support, as just another proxy war between foreign powers, it was the organic result of the crisis created by colonialism. In this sense, the struggle was inevitable, even though victory was far from certain. Fidel Castro rose to the challenge. He passed one of the key tests of the era. But this is not a question of personal moral virtue. Castro was not a saint, but he was no demon either. Freedom fighters like Mandela demanded an ally, and El Comandante gave them the answer they wanted.

Photographs courtesy of Marcelo Montecino and United Nations Photo. All published under a Creative Commons license.