When accompanied by music that seems to drift in and out of focus, as if it were being heard from a neighboring houseboat at some no-frills marina, the word “slack” forces itself ineluctably into the listener’s mind. But whereas the adjective served as an anti-corporate rallying cry on Superchunk’s foul-mouthed first single back in 1989, it now conjures something more subtle, the different kind of tension that saturates a world where it’s hard to stay taut.

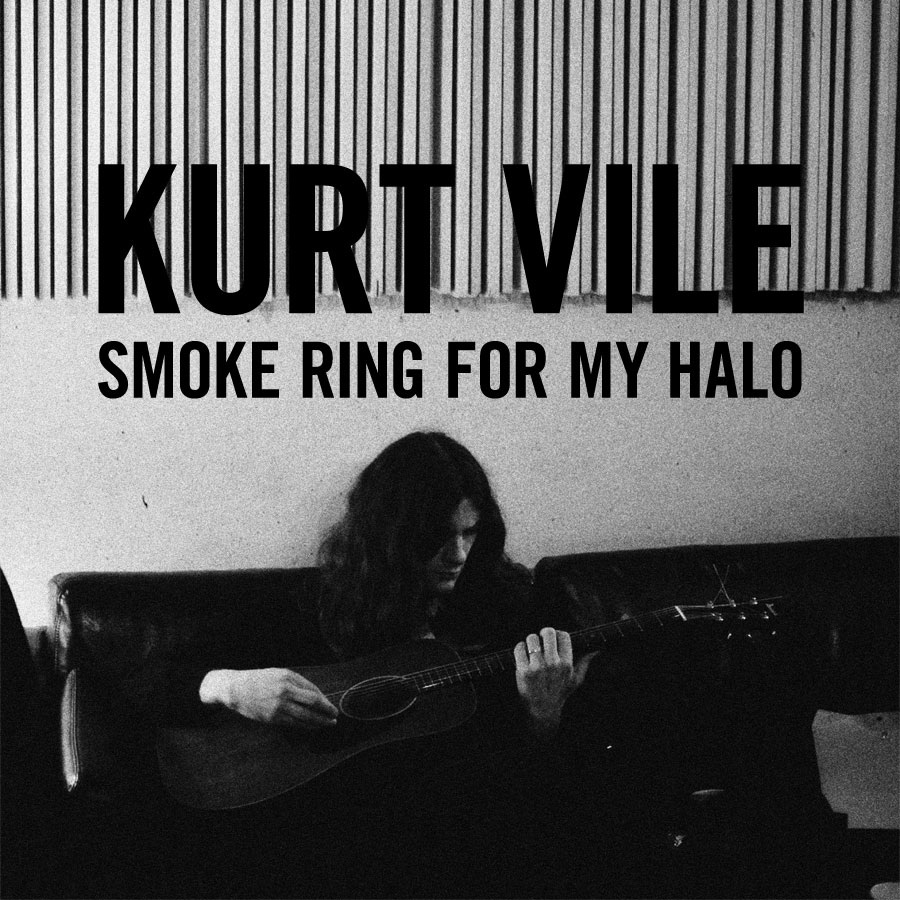

“Runner Ups” perfectly distills the ambivalence that saturates Smoke Ring For My Halo. Over the resonant finger-picking that distinguishes Vile’s best guitar work, he demonstrates how lack of vision can serve as a defense mechanism. “When I’m walking my head is practically dragging/yeah, and all I ever see is, just a whole lotta dirt,” Vile sings, turning the concept of worldview inside out. But even though he is reluctant to look up, it’s not because he doesn’t care about what lies over the horizon. As he half mumbles towards the end of the song, “When it’s looking dark, punch the future in the face.”

Kurt Vile’s musical persona isn’t numb, though he might prefer to be. And he works too hard keeping his head down to qualify as passive. In short, he’s the perfect spokesperson for his generation, the kids who grew up on the “alternative” culture of the 1990s without being able to identify with the animus that fueled it. Yet because his generation’s predicament is also the purest form of a problem facing everyone who seeks meaning in popular culture these days, Vile also has the potential to be a representative for our era.

It’s hard to discern meaningful trends in popular music these days. The size of the marketplace may be shrinking, but there are more and more stalls shoved together within its confines. Instead of a tidy chain store, where the difference between goods is softened by the sterility of their presentation, consumers confront records like tourists from a prim American suburb navigating a Middle Eastern souk. There are too many choices and a dearth of reliable guidance.

Do the melons this vendor is touting taste sweeter than those of his competitors? Is the hammered metal of this pot really as coppery as it appears? Will the steep discount at this stand be negated by the fact that the proprietor’s scale is off by a quarter pound? Music fans of today agonize over similarly difficult questions, whether deciding what to buy – admittedly a less common pursuit than it used to be – or merely what to spend their time on. Aside from a few mega-selling hip-hop acts and the young, female singers beloved by the tabloids, even sales charts demonstrate a profound lack of consensus.

But just as the souk offers more opportunities for entrepreneurs than “big box” shopping plazas, the contemporary music business makes it easier for up-and-coming artists to make a mark. Whereas it was once the case that only artists promoted by the major labels were likely to have ancillary forms of money-making, like placing songs in movies and commercials, today the barriers to financial success are far more permeable.

To be sure, the definition of “success” has shrunken in scope. Instead of a massive entourage and similarly sized budgets for drugs, alcohol and damage compensation, most artists of today are content if they cover expenses with a little left over. Should a one-time windfall enable the purchase of a car or house, they’ll be positively thrilled. In other words, the grandiose dreams of being a rock star have shrunken to decidedly more bourgeois aspirations.

It is in this respect that the souk analogy proves most illuminating. Like the teeming mass of entrepreneurs that fill that traditional marketplace, the contemporary music business is increasingly dominated by people with modest goals and concomitantly scaled-down aesthetics. While those who still aim high may be admired for their quixotic approach, they are regarded, like the fictional nobleman of La Mancha, as relics of a bygone era. Today it’s the realists who lead the discussion.

That’s why artists like Kurt Vile are perfect for the times. Smoke Ring For My Halo proffers a bevy of songs that manage to please without ever seeming like they’re trying too hard. He’s like a fruit merchant who trusts that his homegrown wares will prove tasty enough to discerning customers that he doesn’t have to trumpet their virtues too loudly. Those who want what Vile is selling will seek his work out. If he is blessed with a way of suddenly increasing his audience, as was the case after HBO came calling, he won’t turn the business away. That said, his plans for expansion are limited by the scope of his aspirations.

Immediately listenable yet full of staying power, meandering without ever seeming random, Vile’s new album does more than enough to justify his presence in the marketplace. What it doesn’t do – and, indeed, doesn’t try to do – is make a case for a bigger footprint there. If you ask many of his advocates, they’ll say those qualities are what make his music great.

But this easy encomium misses the point. Because no matter how good Smoke Ring For My Halo is, the record goes out of its way to sidestep the problem of scale. It’s not “great” because Vile understands about as well as any musician that the contemporary music business calls for art that aims low, but at targets it can hit consistently. And here he hits the bulls-eye over and over, even if it’s only ten yards away.