2012 was a year of rude awakenings in Germany. The revelations surrounding the National Socialist Underground terror cell, which had been allowed to murder at least ten people (nine of which were minorities,) were followed by even more disturbing indications of incompetence on the part of the security services tasked with policing them. The disclosure of crucial mistakes in the hunt for the NSU, and of the shredding of documents relating to the case at the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (the Federal Office for Protection of the Constitution) led to the resignation of agency head Heinz Fromm, and an ongoing political headache for the Merkel government.

It is against this background that the Bundesrat recently took up the issue of banning the Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD), the largest and most visible party on the radical right wing of German politics. The NPD constitutes a peculiar problem for the German polity. It represents the nexus points of the two most important political imperatives of postwar German political life: the defense of liberal democratic values and the necessity of working through the fascist past.

In no country has the legacy of European fascism been so vexing as in Germany. At the end of the Second World War, when evidence the crimes of the National Socialist regime impressed itself most immediately on the public consciousness both in Germany and across the west, the imperative of coping with this heritage was overtaken by the need, perceived by the governments of the victorious allies as more imperative, of prosecuting the nascent Cold War with the Soviet Union.

The Cold War shaped the reception of the heritage of National Socialism in ways determined by the political imperatives of the respective sides. In the allied occupation zone, and in the West German state that grew out of it, the process of denazification, viewed as crucial by the allied leadership in the waning days of WWII, was soon deemphasized in the face of the struggle against international communism. Matters were different in the east, where the struggle against National Socialism figured into a broader political narrative of conflict with the bourgeoisie in the late stages of capitalism. In defending his choice to join the Communist Party in late 1945, the Jewish diarist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Klemperer noted that, “[i]t alone is really pressing for radical exclusion of the Nazis.”

In neither state was sympathy for National Socialism ever fully eradicated. Survey data from West Germany showed a significant minority (44%) thought there was more good than bad in the recent past. It was only in the 1960s with the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, and the coming of age of a postwar generation, that the process of working through the past began in earnest. In the east, positive memory of the Nazi period, but also attempts to work through that era, were rigorously discouraged. The degree to which the communist order had merely suppressed, but not eliminated, far right sentiment, was illustrated by the spate of attacks against foreigners that broke out after the fall of the Berlin wall, most prominently the riots in the Lichtenhagen section of Rostock, in August 1992.

The NPD was founded in 1964. In the near half century of its existence, it has had some success in making its way into state level legislatures. However, the party has never managed to reach the 5% threshold at the national level that would result in representation in the Federal Parliament. Originally, the party’s strength was predominantly in the south and rural areas. In the late 1960s, the NPD won 15 seats in the Bavarian Landtag, and 10 in Lower Saxony. The addition of the “neue Bundesländer” (new federal states) to the German polity proved a boon to the NPD. The party has been able to capitalize on the depressed economic conditions in the eastern states, where unemployment has routinely run at twice the level of the western states, and its political rhetoric has also managed to mobilize anti-foreigner and anticommunist sentiment that had bubbled below the surface during the era of the German Democratic Republic.

The politics of the NPD are explicitly nationalist and racist. Their attitude towards the memory of the Nazi past is aptly illustrated by the walkout staged by 12 NPD deputies from the Saxon state assembly during a commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. Party leader Holger Apfel subsequently gave a speech to the Saxon parliament, in which he accused Allied forces of mass murder in the case of the bombing of Dresden. National party chairman Udo Voigt described the bombing of Dresden as a “holocaust of bombs,” a turn of phrase which nearly resulted in his prosecution under the law forbidding denial of the Holocaust.

The first effort to illegalize the NPD was made in 2003. This was, it should be noted, not unexampled in the history of postwar Germany. The government of West Germany had illegalized the far right Sozialistische Reichspartei in 1952, and had banned the Communist Party in 1956. In both cases, the grounds cited were that the party in question presented a danger to the maintenance of the constitutional order. The first attempt to ban the NPD was blocked by the Federal Constitutional Court in Karlsruhe. The main reason for rejecting the attempt was that the federal security services had so shot through the NPD’s leadership with informers and agents that the court said it could not be sure whether the party’s policies were its own or the result of the influence of provocateurs.

The most recent move toward banning the party got started in 2011, when claims were raised by the security services that the NPD had connections to the Zwickau NSU cell. It was claimed that Patrick Wieschke, a leader in the NPD’s youth organization, and Ralf Wohlleben, a former NPD chairman from Thuringia, had both had context with members of the NSU cell. Wohleben is currently facing charges relating to these connections. Whether as a direct result of this, or stemming from a more general assessment of threat based on the actions of the NSU cell, the Bundesrat (the upper house of the German parliament) has taken up the issue of a renewed attempt at a ban.

A vote was taken in mid-December, with the result that 15 of the 16 federal states were in favor of the ban. The single dissenting vote came from Hessen, where the state justice minister, Jörg-Uwe Hahn, pointed out that a renewed attempt to ban the NPD posed certain dangers. Most prominently, an attempt to ban the party that once again failed to pass muster in Karlsruhe would likely have the effect of increasingly the visibility and credibility of the NPD. So far, the German government has not taken further action on this proposed measure.

All of this raises the question of what is to be done if not illegalization? In answering this question, much depends on precisely what one views as the scope of the problem. In addition to news coverage about the actions of the NSU cell, there have been further disturbing items in the news of late. A recent story in Die Zeit indicated that the number of violence prone members of the far right had risen above 10,000 nationwide. Der Spiegel has provided extensive reportage on the situation at Borussia Dortmund, one of Germany’s most prominent football clubs, where far right activists have apparently infiltrated not only the fan groups, but also the corps stewards employed by the team for crowd control during matches. Concerns have been raised about infiltrations at other sports organizations as well.

There is an important sense in which the NPD is merely the tip of an iceberg. The far right of the German political spectrum is scaffolded on a web of thinktanks (such as the Kassel-based Thule Seminar,) journals (Criticon, Sezession, Elemente,) publicists, and political parties (the Republikaner and the NPD.) The NPD is only the most visible and most radical of the right wing parties that actually take part in the political process. The desire to limit their influence runs up against the goal of German liberal democracy, central to the governing ideology of the state in the postwar period: the ideal of political openness, based on the goal of not reconstructing the repressive political order of either National Socialism or the GDR. In the course of the debate, the Minister President of Thuringia, Christine Lieberknecht, argued that it was up to the state to, “defend itself with all means available to the legal order against a brown horde that wants to destroy the rule of law.”

The history of Germany in the 20th century is an object lesson in the dangers of allowing political entities committed to the destruction of liberal democracy to take advantage of its freedoms. At the same time, it remains unclear whether the attempt to ban the NPD can pass constitutional muster. The far right remains a small minority in Germany, and it is worth noting that it is also the subject of intense anti-fascist activist at the grassroots level. While there has been some willingness on the part of local authorities to work with anti-fascist activists, the German state tends to be leery of leftist organizations, fearing that they will create a similar problem at the other end of the political spectrum. Yet, the attempt to cope with this problem runs the risk of damaging German democracy. It remains to be seen if those committed to its preservation can develop an effective strategy for coping with its opponents.

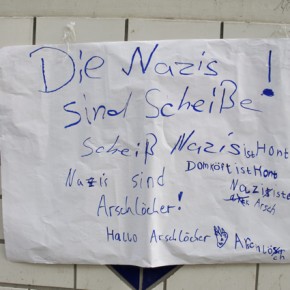

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit