In a Maximum Rockn Roll column in 2005, Felix von Havoc stated that we’re in the” throwback era” of music. Try as I might, I can’t escape the feeling that Havoc’s insight has been one of the more salient observations made in the past decade. It cuts to the core of a very important issue. Most music, mainstream or underground, is nowadays judged in terms of what it is a “throwback” to. Has rock reached a cultural cul-de-sac?

We’re two years now into a new decade. Depending on who you ask (say, Killing Joke’s Jaz Coleman,) 2012 may very well be the last year of man on Earth. And yet many new bands are still judged to be good precisely because they seem like a throwback to something that was either prominently very good (like Lady Gaga recalling Madonna’s heyday), or something underappreciated (like Burnt Cross recapturing the spirit of 1980s Crass Records anarcho-punk, or Pissed Jeans‘ beautifully damaged take on Flipper and Black Flag,) from back in the day. What way(s) forward are there? More precisely, what way forward exists for hardcore punk, or plain old punk, and/or other traditionally countercultural genres of music that have historically despised nostalgia, and the status quo? (Or is the assumed continuance, or continued relevance, of genres like punk itself, an admission of missing the point?)

Minor Threat’s last song, Salad Days, evinced pure disgust at folks who stayed trapped in a time warp of the “good old days.” Eight years before Minor Threat’s last song, Johnny Rotten was captured in a famous photo flipping off images of the Beatles on a backstage wall. The subtext was a refusal to accept the past, and the culture of elder authorities, as the prime determinant of the cultural future.

England’s Angry Brigade commented on that sort of cult of retro-fascination in 1971 when, in Communique #8, they wrote: ” “All the sales girls in the flash boutiques are made to dress the same and have the same make-up, representing the 1940′s. In fashion as in everything else, capitalism can only go backwards — they’ve nowhere to go — they’re dead.” Shortly after the release of Communique #8, the Biba fashion boutique in posh West London was bombed by the British militant group. “Life is so boring there is nothing to do except spend all our wages on the latest skirt or shirt,” the Communique continued. “Brothers and Sisters, what are your real desires? Sit in the drugstore, look distant, empty, bored, drinking some tasteless coffee?”

Even the Black Panthers’ Huey Newton seemed partial to this kind of sentiment in the same era when he bitterly wrote, “Youths are passed through schools that don’t teach, then forced to search for jobs that don’t exist, and finally left stranded in the street to stare at the glamorous lives advertised around them.” Nowadays youths might do these things as well, but take photos for Facebook and Tumblr accounts to show how bored, indeed, they are — drinking coffee and surveying glamorous lives around them, just as in the past, albeit maybe with a few “likes” clicked on their profile.

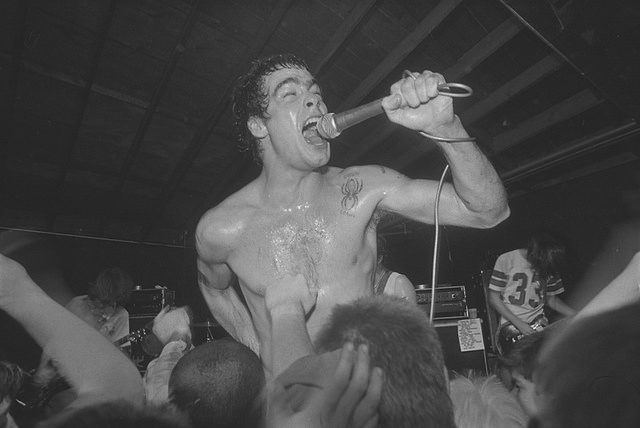

While it’s easy to think of the older, ’80s punk bands that more modern hardcore bands like Career Suicide or Government Issue remind us of (and those are two very good modern bands, by the way), what previous style of music was 1982-era Black Flag a “throwback” to? What were Bad Brains a throwback to? There was certainly a lot of frenzied and eccentric 1950s rockabilly and 1960s underground garage rock. But while you can say that Career Suicide clearly remind one of Jodie Foster’s Army or the DC hardcore band Deadline, for example, you cannot say that Minor Threat in 1981 remind of any ’60s or ’50s musical act in the same way.

True, all bands are informed and/or are influenced by some other type of earlier music. For example, rowdy, 12-bar blues and hillbilly country clearly informed early rock and roll. 1977 punk rock informed the blisteringly fast assault of ’82-era US hardcore. Music is rarely, if ever, truly sui generis. But 1950s rock’n’roll was its own beast, and was not a throwback to anything else the way a Discharge clone band in 2012 is, well, a Discharge clone band, recalling a style of music made thirty years before.

One of the better new hardcore releases from 2011 came from Greece’s Sarabante, whose Remnants LP on Southern Lord was produced by Brad Boatright of From Ashes Rise and World Burns to Death. (For that matter, Southern Lord has lately become a major go-to label for exceedingly good dark neo-crust.) On Sarabante’s Remnants, a rich and bottom-heavy production complements epic — to use a popular term – and almost ballad-like guitar-driven melodies; these are generously laid over a core of relentlessly forward-charging heavy thrash. Black metal influences seem to appear in the emphasis on minor notes used in the guitar breakdowns. As always, a lyric sheet is essential to understand what the band is saying (and this would be the case even if the band wasn’t from Greece.)

As with most current, dark, d-beat neo-crust, the overall message has to do with the decay and breakdown of modern society. And, also as with Tragedy and Wolfbrigade, an ecological tinge is coupled with a pessimistic survey of the prospects for anything politically or socially better than what we have now. Everything’s fucked, and it will only get all the more so in the near future, the message seems to be. No way forward is proposed to get out of the mess. Sarabante and other similar bands might (rightly) say that, as artists, it’s not their job to formulate such a way out. Since when is hardcore, or any type of music, supposed to be about progress?

Sarabante’s debut LP is a damned good record. But it’s hard not to feel that even this LP is the beginning of a throwback to early 2000s dark, neocrust hardcore. Producer Brad Boatright’s band From Ashes Rise released the excellent Nightmares LP on Jade Tree in 2003, which some at the time laughably called a sellout record! — and you can certainly feel that influence in the Sarabante material. Japan’s Muga can also, importantly, be heard in the mix. Way ahead of the curve, Muga made an insanely great, self-titled release in 2001 (as well as a “Road to Asura” cassette-only (!) release) that seems to have laid down a template for almost every band in this “dark, epic hardcore” niche since then. (See their song Grotesque, for example, from their self-titled 2001 LP, and compare to later releases by Summon the Crows, Ambulance, Behind Enemy Lines, Ekkaia, Derrota, Invasion, etc.)

Sarabante’s reveling in all the best conventions of modern, dark neocrust is actually a kind of delicious thing to aurally behold – like savoring your favorite comfort food on a party platter while you lounge on the sofa. One is tempted to short-list it for a primer for anyone who wonders just what the state of modern underground DIY hardcore punk is. Darkly melodic, and yet fast as hell, and made by people who obviously know how to play their instruments (not something to be overlooked in underground hardcore!) — yet who also know the definition of “nuance.” And all this from musicians who also seem to “get it” when it comes to the DIY ethos. Sarabante’s Remnants fires ahead flawlessly on all cylinders. And yet — overall, there is an aura of throwback to the material, too. It is, after all, called Remnants. Are these the remnants of the gloom-heavy, dark neocrust trend making their last (albeit compelling) stand?

Anecdotally, I can tell you that most people I know feel the best music ever made *ever* was between 1976 and 1985. Maybe they don’t agree whether the music made in that time period came from the purist punk rock, new wave, the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, hardcore, goth, postpunk, or even raw experimental noise scenes, but most of the people I talk to seem to think that everything that could or should have been said musically was said in between those ten years, and that everything since is basically a reaction to, or elaboration of, that moment. I’ve encountered this sentiment in millennials and Generation Y types, too; it doesn’t seem to be something that only old hardcore punk fogies from Generation X or the Blank Generation purport to feel. And it’s a compelling belief.

Granted, there are newer sub-genres that have their adherents and which critics could point to as evidence to refute anything I’ve said thus far about a cul-de-sac in modern underground music. But, boy, do a lot of those new (sub-)genres of music suck. The electronic and EBM dance music styles soldier on stubbornly, mostly inspired by slick ’90s/celebrity DJ/club music trends. In this light, something to be kept in mind is that new type of music does not necessarily equal a “good type of music.” The wanky, meandering, acid-trippy prog-rock of the 1970s was itself a new type of music for its time, i.e., it was not a throwback to anything before — but that does not mean that, since it was new, it was great.

Ten-minute electric guitar odysseys were new on the scene in 1972, but they weren’t great or especially worthy of praise because of that fact. In my opinion, developments like rave or acid house – no matter the sorts of pretentious political manifestoes one might try to slap on them retroactively, like stuff about Temporary Autonomous Zones – were just as bad as the disco genre before them. And for that matter, disco was itself another “new” sort of music from the mid and late 1970s that, although novel, did and does not represent anything especially wonderful or meaningful. “Indie disco” or “alt-disco” are newer genres you might see advertised on flyers for an event night at a club in your hometown. All that means, ultimately, is that the music that you will hear will suck. Disco will always be disco, no matter its incarnation. Caveat emptor!

As far as the current backwards-looking trend of music goes, I’ve always felt that if there was a Hell, at least one of its circles would consist of an eternal ’80s night. Having said that, there are a few trajectories I can see punk rediscovering to move ahead. As far as pop music goes, I don’t have a dog in that fight. No one can predict the direction that that will take. (Justin Bieber or Katy Perry?) But hardcore punk? Here are some scenarios:

1. Industrial punk

Do you remember Pailhead and Lard? What happened to bands like that? I don’t mean ’90s industrial metal like Fear Factory or Chemlab or Gravity Kills. I mean full-bore, no-holds-barred, aggressive, fast, political, industrial hardcore punk. In the late 1980s this seemed like a possible and viable way to go forward, hence why people like Ian MacKaye, Jello Biafra, and others (temporarily) signed up. Optimum Wound Profile notably seemed eager to plow ahead in this direction (see Tranqhead from Optimum Wound Profile’s Lowest Common Denominator LP on Roadrunner, a Crass-ish, yet accessible, industrial punk release weirdly ignored while the mainstream music press was masturbating over Nine Inch Nails.)

Remember Nausea’s Cybergod? Christdriver and Titwrench also made some compelling lo-fi, hi-tech industrial thrashcore songs. Neurosis and even the Swans (“I Am the Sun”) seemed primed to go in this direction, too, until a lot of them went off into “post-rock” territory. Wired’s™s Read and Burn, Killing Joke’s ’90s material, and the 2005 PESD POLITIKAREPOIZONEKURVAE LP, on Prank Records, also remind us of the potential left laying at rest in this under-explored niche of music. It’ss sonic territory that remains to be fleshed out, but is full of promise.

2. Modern Post-Hardcore

Bands like Kim Phuc and The Conversions are doing a new kind of update on 90s post-hardcore that has taken into account the dark, d-beat experience of the past decade. Check out the 2011 Copsucker LP by Kim Phuc, a band that contains ex-members of Aus Rotten. It sounds like ’90s “post-hardcore,” and, yet, it doesn’t. Iceage also tread this terrain brilliantly. Kim Phuc’s Animal Mother/Local Round-up is as good a song from the hardcore scene of 2011 as I’ve heard.

3. Acoustic Neofolk?

This might seem counter-intuitive, but given the “MTV unplugged” nature of bands like Ian MacKaye’s The Evens – described as “post-post-hardcore” by some writers – it might not be that far of a stretch. Death in June are as popular as ever even though the act consists of the singer (Douglas P.) merely strumming an acoustic guitar, sitting on a bar stool, albeit in WWII camouflag garb. Zounds’ Steve Lake made a similar “stripped to the acoustic basics” concert tour recently. And bands like Sonne Hagal, Rome, and Darkwood are basically coming on stage with acoustic guitars, kettle drums, and a Joy Division-esque appearance, claiming roots with punk bands in the past. Coffeeshop postpunk? The Evens would never say they are neofolk, but what is the current interest in back-to-basics, guitar-driven melodic music – yet in the context of punk or alt-underground – indicative of? Billy Bragg has been there all along.

4. Post-Black Metal

Bands like Hateful Abandon, Lifelover, Bone Awl, and the newer Darkthrone releases have been combining a kind of dark postpunk with 90s black metal and garage music. Witness the recent Darkthrone cover of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ “Love in a Void,” for better or worse. The Lost Sounds’ Memphis is Dead 1999 LP on Empty Records could be seen as a precursor of this particular cocktail of postpunk, deathrock, and black metal. (See Satan Bought Me, and other tracks off that Lost Sounds release:.) Acephalix from San Francisco, and Tyrant from Sweden have taken their cues from Hellhammer and Darkthrone but are also mindful of influences from Naked Raygun and the Wipers, too.

The cross-pollination between postpunk, hardcore, and black metal is an especially interesting area of current music germination, and it remains to be seen what can be wrought from this fertile cultural matrix. Circle of Ouroborous have recently pulled off some incredibly dreary, melancholic tracks that simultaneously recall Joy Division and Darkthrone. (See their Demon in Iron, something that sounds like it could be a 1979 Joy Division demo if Ian Curtis had just listened to Burzum.)