People warned me about punk, two in particular. The first was Judith, who was two years older than me and whose father taught computer science at the liberal arts college in eastern Washington state where my father was the dean of the faculty.“You need to be careful,” she told me, “punk in the cities isn’t like it is here.” Judith was a bright person, but she was one of those well-adjusted people who aimed to be student body president at an Ivy League school (and probably ended up achieving her goal). I didn’t put much stock in what she had to say.

Among the small set of punk rock kids in my hometown in the early 1980s, we’d read enough issues of Maximum Rock’n’Roll and Flipside, rewatched UK Decay and Suburbia enough times that we felt like we had a grip on what was going on.

The second warning came from my buddy Jerry who found out that I was going to be moving to Nottingham in the UK for my senior year of high school.

“They’ll probably just kick your ass,” he told me. Jerry was convinced that he was a lot cooler than I was (he was probably right about that) and bitter that I was getting to move to somewhere where things were happening. I took that with a grain of salt too.

Punk rock, from its inception in New York, London, LA, and half a dozen less storied locales to its metamorphosis into the hardcore scene of the early 1980s, was very much about space. Punk arose among small cells of eccentrics and outcasts congregating in places like the King’s Road and Greenwich Village. But it was also about distance, the capacity of these little scenes to broadcast their cultural influence into the peripheries and hinterlands and to undergo transformation through the feedback loops that these processes of dissemination created.

Punk bounced into eastern Washington in the early 1980s, spawning little sets in places like Walla Walla, Moses Lake, and Tri-Cities. It produced numerous bands, mostly short-lived, and none greater than Richland’s Diddly Squat, whose Peroxide in the Scablands demo is one of the hidden classics of the region.

Diddly Squat bassist Nate Mendel ended up, after many twists and turns, playing in the Foo Fighters, alongside former Germs guitarist Pat Smear. If you’d told any of us in the little eastern Washington wheat towns back then that someday we’d be three degrees of separation from Darby Crash, or Billy Zoom, (or Belinda Carlisle for that matter), we’d have been pretty sure you were nuts. But punk is a small town mapped out across the world.

As with all towns, if they survive long enough, their history will come to be written. The history of the London punk scene has been documented thoroughly, in works such as Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming and Marcus Gray’s Clash biography, The Last Gang in Town. Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me is pretty much the state of the art in terms of the history of the early New York punk scene and its roots in the set around Andy Warhol and its connections to middle America (for instance in the scenes in Michigan that generated the Stooges and the MC5).

The scene in Los Angeles, arguably the most complex and vibrant of them all, has not received quite the same degree of coverage. The best book up to this point has been Brendan Mullen (former proprietor of the legendary Masque) and Marc Spitz’s We Got the Neutron Bomb. That book, which is structured a lot like Please Kill Me (i.e. an oral history composed mostly of shorter quotes). Under the Big Black Sun: A Personal History of L.A. Punk makes an excellent companion piece to that work.

Former X bassist John Doe is listed as the author, but it might be more accurate to say that he curates it. The book is composed of a series of essays by various prominent figures in early L.A. punk, including Exene Cervenka, Jane Wiedlin, Charlotte Caffey, Mike Watt, Henry Rollins, and Jack Grisham (to name only the very most prominent). Doe himself adds several pieces, almost at times seeming like the chorus in a Greek tragedy.

And make no mistake, this story has some very tragic elements. The narrative takes us from the heyday of the scene, when a bunch of assorted freaks, nerds, and ne’erdowells came together in the partly abandoned heart of post-industrial downtown L.A. to create bands like the Screamers, the Weirdos, X, and the Germs. The created a golden age, with performances at the Masque (in the basement of a down-market porn theater) and parties in the Canterbury, and grungy apartment building where dozens of faces from the scene lived at any given time.

The scene in the early days was open and inclusive. Women played important roles. Exene Cervenka fronted the scene’s most prominent band. Belinda Carlisle preceded Don Bolles as the drummer for the Germs before forming the all-girl Go Go’s. Gay was ok, and there was an interesting cross-pollination of ethnic cultures as downtown scene synergized with bands from East LA like The Brat, The Plugz, and The Zeroes (who were originally from San Diego, but still…). There were feuds and beefs, even the occasional fight, but people mostly got along and the scene thrived on the variety of styles on offer.

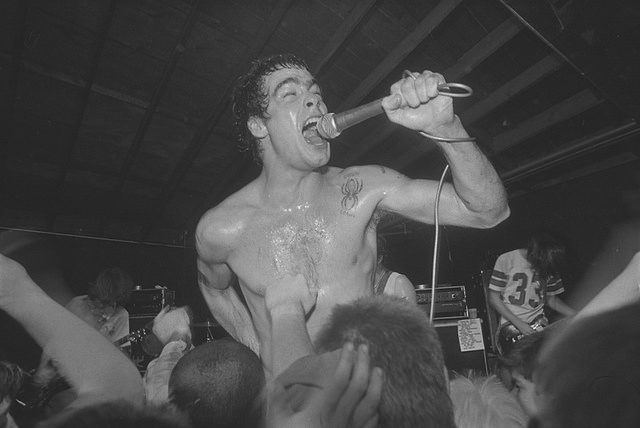

All this began to change around 1980 with the emergence of the hardcore scene. Kids from out in the suburbs with no experience in or connection to the older crowd flooded into the scene. At the same time, the music became harsher and more aggressive, once again with bands coming in from more far-flung regions. No band more epitomized this than Hermosa Beach’s Black Flag, who ramped the level of anger and aggro up to levels never previously seen.

Often times collections of essays can seem fragmented, but those collected in Under the Big Black Sun effectively chart the arc of transition from the golden age to the rise of hardcore, which was both collapse and transition. Perhaps the book’s most effective moment comes at the beginning of the piece by former Blasters guitarist Dave Alvin. The Blasters were an oddity in the scene: essentially a straight up rockabilly band who play with the punks because the liked them and enjoyed their company. In the earlier era that worked well, as people were not terribly concerned with genre boundaries and the Blasters music was not all that different than that of X or the Gun Club. But the tenor of the scene changed with its audience, as Alvin makes clear:

“Those of us who are about to die…salute you!”

With those words Lee Ving, the lead singer of the ferocious punk band Fear, raised a beer to us Blasters as he stopped by our open dressing room door. We laughed nervously, raised our beers, and saluted him back. Then he walked down the long, smoky hallway and on up to the stage of the gritty, old Olympic Auditorium just south of downtown LA to face five thousand restless and agitated punk kids. It was New Year’s Eve 1981, and we were sharing a bill with not just Fear but also the relentless noise-jazz-punk of Saccharine Trust, the art-punk veterans Suburban Lawns, and, most intense of all, the headliners were the fierce, brilliant kings of hardcore, Black Flag.

There was no applause as Fear was announced, but in those days there rarely was any applause at real hardcore shows. This wasn’t really a show for people who came to clap, cheer, and celebrate their musical heroes; it was more like a gathering of people alienated from polite consumer pop culture, who wanted to get fucked up past the point of feeling pain, ready and willing to beat each other into bloody pulps in the mosh pit or even attack the bands onstage as a primitive initiation rite into an exclusive alternative society of pain. I couldn’t help but hear the crazed roars, insane boos, and threatening catcalls of the audience upstairs echoing through the cavernous, cement halls of the underground backstage. Mr. Ving’s first words to the audience were simple enough: “We’re Fear. Fuck you!” This sent the crowd into a rage of even louder boos that quickly grew into throat-ripping shouts and booming death threats. Something ugly was going on up there, or was just about to. Between the drunk, unruly crowd and the overzealous security guards, more than a few people were probably going to get the shit kicked out of themselves tonight.

[…]

“No slow songs tonight,” my brother Phil commanded as I wrote out our set list. I agreed wholeheartedly. There would be no arguments between the Alvin brothers on this night. I looked around the dressing room at bassist John Bazz, pianist Gene Taylor, and drummer Bill Bateman and announced, “All right. We open up with ‘High School Confidential’ and the we don’t stop playing even if someone gets killed.” I smiled, but I was only half joking. Bill stared back at me with a blank-stone face and said, “Anybody fucks with me and I’ll kick his fucking ass.” Gene just laughed: “If any trouble starts, Bill, you’re gonna have to kick three thousands crazy motherfuckers’ asses. Good luck with that.” “Hey, fuck you, Gene,” Bill shot back. Then we drank more beer and prepared to die.

The real virtue of Under the Big Black Sun is the way that it works counternarratives into the story. TSOL frontman Jack Grisham provides an essay written from the perspective of the younger hardcore kids who felt bitterness and betrayal at not being accepted by the older crowd, even as the older crowd felt that the hardcore kids were smashing the scene entirely. And, once again, we see the influence of space: the close-knit familial scene of people and places within walking distance of each other, inhabiting spaces made available by the collapse of heavy industry in the region and the resultant urban decay in the center of the city. And then the destruction of this scene by latchkey kids streaming in from the suburban sprawl, looking for something to believe in, or maybe just something to smash.

There are a lot of interesting takeaways from this book. In a certain sense, the most interesting is what can be gleaned from former Minutemen bassist Mike Watt’s recounting of his chance meeting with D. Boon and their formation of their own micro scene in the isolated L.A. port section of San Pedro. Watt is brilliant in a down-to-earth way, mixing a sort of jaundiced view on the scene with a love and respect for the spaces that it opened up (if you haven’t watched the Minutemen documentary We Jam Econo it’s probably the next thing that you should see). It is one of the ironies of this history that the Minutemen, whose offbeat, jazzy take on punk recalled the earlier era, entered the scene in the company of Black Flag, arguably the arbiters of its demise.

Much as this history is a history of the fall, it is nonetheless beautiful and fascinating. The members of the scene from the early days all express a certain degree of sorrow that it couldn’t last, but they mostly seem to retain a certain joy in having created something novel. This is, it should be said, always the way with such things. The eternal fact of culture is change, and no good thing lasts forever. But it is important that these moments, however, brief and fleeting, should remain in memory, so they can be both remembered and ignored by the next crop of iconoclasts.

Photographs courtesy of UCLA Library Special Collections. Published under a Creative Common license.