Punk had a midlife crisis during the summer of 1994. “Corporate whores” and “ass-kissing sellouts” were shouted at the Offspring during that show, the Sacramento Bee reported. “So you guys know us for our whole album and not just one song, right?” frontman Dexter Holland reportedly told the crowd. “We’d like to think so, but we’ll now patronize the ones who only know that one song, anyway.” Many middle fingers stood high when the veteran Orange County punk band’s first chart-topper, Come Out and Play began.

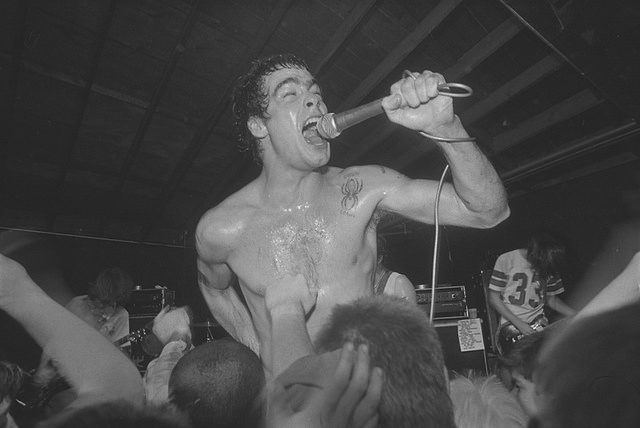

In the title track of their 12-million-copy-selling album, Smash, Holland constantly sings that he’s not a “trendy asshole,” as if struggling to redeem his sins that’ll curse him for years. The revolt against the punk “sellouts” veered into darker terrain that year – a group of slamdancers nearly crippled Bay Area punk icon Jello Biafra and accused him of being a “rock star” at the legendary Berkeley punk mecca, 924 Gilman. “So much for teen spirit – or punk rock as a positive force of change,” critic Gina Arnold snarked about the incident in the Spin Alternative Record Guide’s entry on Biafra’s band, the Dead Kennedys.

I admit it: my 14-year-old self was one of the many “trendy assholes” whose first major exposure to punk rock was via MTV and “whores” like Green Day, Rancid, Bad Religion, and the Offspring. Few teenagers had Internet access back then and you were among the privileged few if you heard about underground bands from your friends, classmates, or fanzines at indie bookstores (a rarity in the suburbs then). Television, Top-40 radio, and corporate-owned entertainment magazines were the only outlets for many of us who were bitterly rejected by those who were involved in punk scenes for years.

I can’t forget the mullet-haired teenager who shot me a glare between my eyes when I examined a CD copy of the Rollins Band’s mainstream breakthrough, Weight, at a Tower Records. There I was, a Stussy-clad runt who was polluting a legacy that began with Rollins’ poverty-stricken years in the archetypal hardcore band Black Flag, which screamed with righteous indignation during the sunrise of the Morning that Reagan promised America. Yet, the music of the sellouts seemed to be groomed for adolescents like me – the three-chord melodies and 4/4 rhythms were pure, high-fructose pop and the singers were man-children bewildered and often bored by modern American life. “Let’s nuke the bridge we torched 2,000 times before!” Green Day’s Billie Joe sang to my juvenile heart’s delight. Whether Rollins would like it or not, Billie Joe and Holland were the “Fuck This!” voices of my young, impressionable generation, as presented to us by MTV.

I recall many summer vacation afternoons watching the channel’s constant replays of Green Day’s pivotal performance at the Pepsi-sponsored Woodstock ’94. Billie bashed his microphone like a breath-holding toddler, thrashed out an open-string chord in “Look, I’m a ‘rock star!’” irony, and ate mud thrown at his face. To answer Oliver Sheppard’s recent question in Souciant about how ’90s punk will be documented, the sellouts will dominate most conventional histories, while a few sentences may mention the punk sub-genres of riot grrrl and queercore as quaint artifacts of Clinton-era identity politics. And if we’re lucky, we’ll have a few more histories of specific scenes – Gimme Something Better, an oral history of Bay Area punk, being an example. During the era that many veteran punks hold in infamy, I imagined punk music and culture to be rock’s frontier where every lyric, melody, and beat went straight to the heart, and there was no pretension whatsoever. It was more than mere “entertainment,” as Biafra put it.

And then I grew bored

The punk music of my time evolved into a non-genre or a lattice of cult scenes and short-lived trends as Sheppard astutely described in his Souciant piece. The ’94 sellout boom arguably reinvigorated punk culture by rallying so many bands, writers, and activists against a common enemy that chased many bands with major label contracts. In that mindset, every note and lyric had to matter as independent music culture’s war cry against a soulless monoculture. The ideology now seems quaint in our MP3 age when fewer people believe that recorded music has monetary value and every “underground” artist and band seems to be aboveground (Japanese noise icon Merzbow can be accessed alongside Justin Bieber on iTunes).

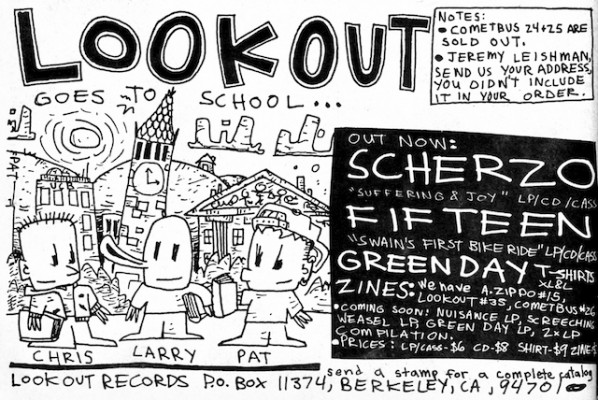

There were several post-punk, hardcore, post-hardcore, ska, garage, and noise-punk bands that caught my ear while I explored punk in the pages of Flipside, Punk Planet, and dozens of mail-order catalogs during high school. Certain moments stick out: Amy Farina’s rhythms that snaked through my headphones in the lone album of DC punk minimalists The Warmers, The Frumpies’ and Deerhoof’s reduction of punk rock into unholy industrial clamor on the landmark Kill Rock Stars/Lookout compilation A Slice of Lemon, the New Bomb Turks’ declaration that “Living in a recession is good!,” and the eerie, cortex-melting interplay of corrosive bass and guitar drones in Fugazi’s Version. I tried to keep up with the media-fueled discourse about punk’s status quo and its proposed directions in a few punk magazines but I grew frustrated with the infighting and finger-pointing.

Lookout Records founder and Punk Planet columnist Larry Livermore’s disillusionment and rejection of the punk culture he seasoned had particularly saddened me. What truly ended my interest in so much of 90’s punk culture was the Muzak in countless skateboard and snowboard videos that played on ESPN and “extreme sports” shops. It was difficult to distinguish the generic hardcore dirges heard from so many Pennywise, NOFX, and Bad Religion clones – and the polka beats and grumbling three-chord riffs often drove me to sleep during car trips. Much of 90’s hardcore’s fallout was scattered in the form of discarded flyers, fanzines, freebie compilation CDs, and skateboard company stickers that littered the grass lots of so many Vans Warped Tour stops during that decade. The final straw for me was the reported incident of Warped Tour audience members jeering and catcalling hip-hop group Ozomatli as they delivered their LA-centric mix of Ranchera and Spanish-language raps. I grew to agree with Arnold about punk rock and “teen spirit.”

Nostalgia for bleak days in Reagan’s City on the Hill

The more I grew frustrated with the 90’s punk culture the more I looked toward punk and hardcore in the dawn of the Reagan years. Such music was more meaningful to me as expressions of protest and disillusionment. My father was among the hundreds of thousands of tech workers who got pink slips in Silicon Valley during the first digital age that arose while greed became a Reaganite virtue. I often feared Soviet nuclear attacks as a child while Reagan rattled his saber at Gorbachev. As I grew older I was constantly reminded by my parents about the drug abuse that sunk the 60’s counter-culture into miserable, rehab-loitering self indulgence. Eighties punk, hardcore, and the sub-genres they influenced were my gateway to figuring out the culture that shaped me. The mess of it all was well parodied in Winston Smith’s collages of newspaper cutouts and cartoons that saturated the Dead Kennedys’ compilation, Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death and the darker likes of Crass’ albums.

Early hardcore’s propensity for breaking all hell loose was clearly felt when Ian MacKaye carped, “What the fuck have you done?” before his band Minor Threat’s rhythm section leads a bayonet charge in In My Eyes. Similar excursions were heard in Black Flag’s Rise Above, Youth Brigade’s Moral Majority, and Government Issue’s Lie, Cheat, and Steal. Bay Area ska-punk legend Operation Ivy’s lone album, Energy seemed to be an artifact of a lost paradise in the form of the 924 Gilman club that flourished before the summer of ’94. I encountered a copy that sat next to Joy Division’s Closer at a record shop – guess which one was bought as a depression cure.

Of all the early 80s bands that resonated with me, none stood above Boon and company in the Minutemen. “I speak for language/I speak for history/I am a cesspool” D. Boon laments amid a thick, sunset-lit bassline played by Mike Watt in the Minutemen’s Do You Want New Wave (Or Do You Want the Truth?). Their 1984 epic, Double Nickels on the Dime translated the rage of hardcore into a wellspring of forms (folk, blues, jazz, funk, Creedence Clearwater-style swamp rock), and lyrics that dwelled in fragmented thoughts, frequent self-doubt, and hilarious wisecracks – all of which often seeped into my mind for the past 15 years. My nostalgia of staring at the album’s 40-plus tracks on my CD player when I brought home the record can’t be escaped.

“Punk was whatever we made it to be,” are D. Boon’s words that I want to live by.

Photograph courtesy of theob. Published under a Creative Commons license.