In “Diary of An Anarcho-Goth-Punk Fiend,” Alistair Livingston, a member of the British Kill Your Pet Puppy collective, records the transformational year of 1983 in terse bursts of prose. In clipped entries, he describes how 1983 began with him listening to bands like The Mob and Blood and Roses. By 1984 – the year of punk’s (and Orwell’s) apocalypse — he was trying ecstasy and getting into Psychic TV.

Although it is compacted into a much shorter amount of time, Livingston’s diary entries parallels the cultural trajectory shown in the narrative of Trainspotting (the movie, not the Irvine Welsh novel.) At the beginning of the film, the characters are listening to punk and arguing about Iggy Pop. By the end of the movie, Trainspotting’s main characters are thump-thump-thumping the night away to bad house music and dropping acid. The feeling one gets from both Livingston’s punk journal and from Trainspotting is — “times change.” The culture changes, and people change with it. People might start out punk, sure — but eventually they move on. Livingston, however, continues to write an amazingly good blog on punk and many other topics under the sun. See, for example, his recent entry on the many musical influences that went into punk, here.

In punk’s heyday, from 1977 until about 1983, the culture was in a constant state of flux. As the title of Livingston’s diary reveals, things like anarchism, goth, and punk rock were all bound up into one mostly undifferentiated whole. It’s only in retrospect, with the benefit of thirty-five years of hindsight, that one can identify distinctly “anarchist” or “goth” characteristics in what at the time was a mostly cohesive unit. Even as late as 1983, punk was not perceived as being any special combination of disparate elements. Things were moving too fast for that sort of analysis.

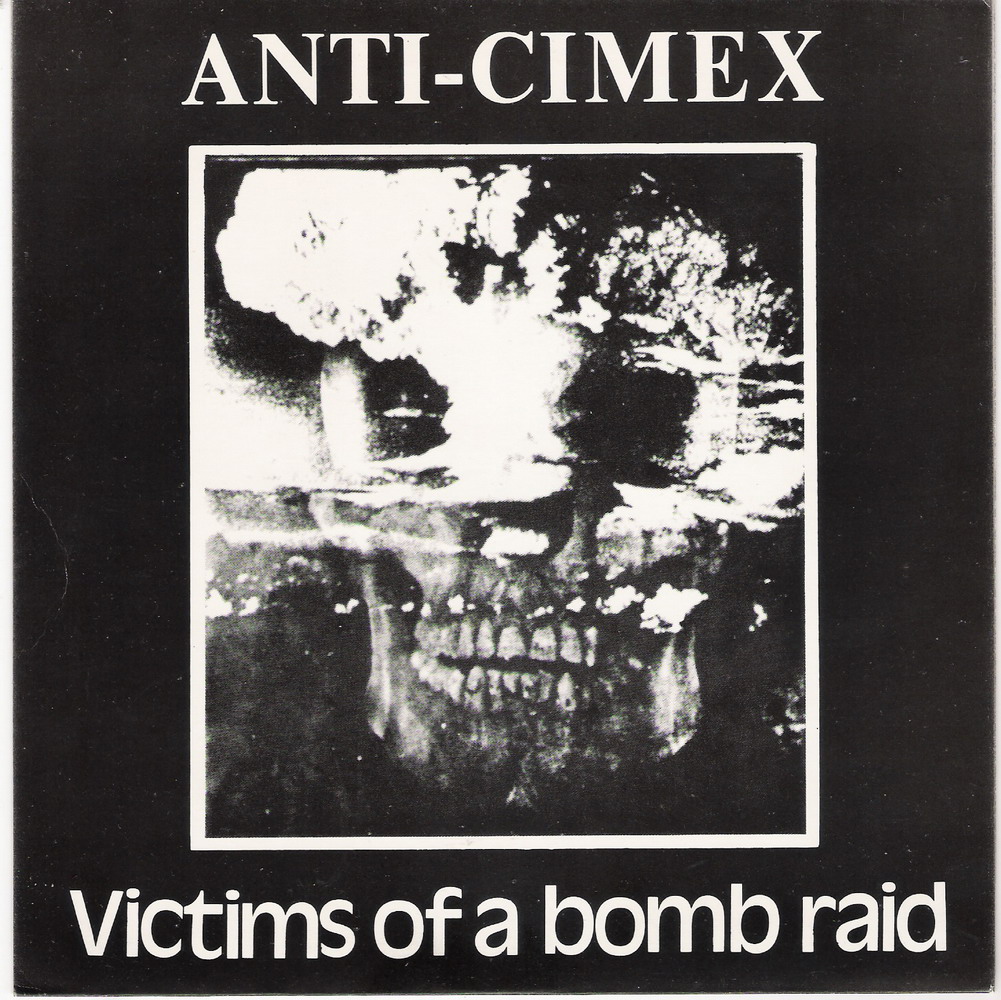

It’s also taken over three decades for individual strands of the punk ball of yarn to become unraveled. Each strand has been teased out gradually as bands have pursued a particular aspect of the punk sound or culture and pushed it ever further out from the center. Amebix hammered at punk’s metal side and created crust, while Siege upped the tempo and laid the foundation for grind. On the West Coast, deathrock explored punk’s gothier side. As Yeats said, “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.” This all happened in such a way that, over time, one punk-derived strand of the culture grew farther and farther apart from the other. In the end, a situation was created such that two distinct sungenres could face each other as complete strangers.

In Critique of Cynical Reason, Peter Sloterdijk wrote that “[S]ociety dissolves into hundreds of thousands of strands of planning and improvisation that mutually ignore one another but are related through all kinds of absurdities – in such a time it cannot do enlightenment, or what is left of it, any harm to reflect critically on its foundations.”

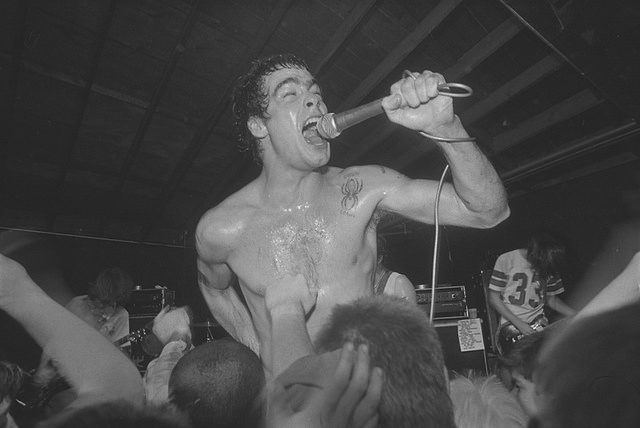

There is one particular strand of the punk explosion that has been privileged as punk’s “real” and continuing heir, however: hardcore. This begs the question: Why should this be the case? Generally, the bands, zines, and fans of this particular branch of the punk family tree have been the loudest in insisting it should be so. If punk, however, could be defined as music in extremis, then there have been other developments in its musical wake that have been even more extreme than hardcore. Grindcore and some types of postpunk, like the power electronics and noise of groups like Whitehouse, have each taken the incipient promise of punk to seemingly reductio ad absurdum – or just plain outrageous – limits. Compared to some of the really outlandish forms of music out there, hardcore can sound downright quaint.

Although we may still be in “the throwback era” of music (as Felix von Havoc noted almost ten years ago), where groups are judged in terms of what music they are a throwback to, a general and promising trend has been the refusal of younger groups to adhere to the cultural logic of punk’s unspooling into a multiplicity of new genres. Younger bands are beginning to recombine punk’s disparate evolutionary strands into altogether new cocktails of sound and imagery. They are re-acquainting cultural aspects of punk that, it once seemed, had happily grown apart.

My own fascination with the new styles of postpunk and deathrock that have been made in the last few years, for example, is partly because I see these trends as punk culture reclaiming its own wayward, bastard children. The music even harkens back to a time when such things as goth were not considered bastard children; the title of Livingston’s “anarcho-goth-punk” diary proves this. (And the new music is just very good on its own merits, whatever larger context it’s put in.) Bands like Blue Cross and Dead Cult practice the punk ethos but are reincorporating aspects of punk once thought to be permanently jettisoned from the main bulk of the movement.

A few things have made this possible. People under twenty-five have grown up in an internet age that presents a smorgasbord of diverse music on a relatively even playing field. In 1985, being into the Thompson Twins was easy; being into DRI , on the other hand, was hard.

In 2012, the cultural space between a hardcore band like Wolfbrigade and a Top 40 artist like Katy Perry has shrunk. This doesn’t mean both are musically similar; it means there is no longer such a thing as true obscurity. There is no longer any sense that being involved with a certain musical milieu puts one onto a remote cultural island, adrift and separate from the mainstream. It isn’t hard to download Rudimentary Peni’s complete discography in a few hours. In the past it would have taken years to track it all down (unless one was especially well-connected to the source of the music itself, i.e. the band and its label).

This cultural fact has been bemoaned by older fans of punk music. Endless and exhausting record hunts at local stores; writing letters to labels advertised in Maximum Rock and Roll; and swapping mix tapes as a way to hear new music or hunt down long sought-after items – these activities have the same relevance now as Black Flag’s mention of shows like That’s Incredible! and Fall Guy in their song “TV Party.” The leveling force of internet file sharing has rendered obsolete all these previous cultural activities. It has also dissolved any sort of informal hierarchy that might have once existed among collectors of punk music.

The upshot hasn’t been entirely negative. If punk was anti-elitist – and in reality, it evinced and does continue to evince an inverse, reactive form of elitism – then at least some of this would be a welcome development. There could and should be a revaluation of the entire corpus (corpse?) of punk laid bare into the full light of the present, with every nook and cranny open to inspection.

The reunification of diverging strands of punk culture – like anarcho-punk, deathrock, and crust being reassembled into unique combinations by bands like Lost Tribe and Alaric – has provided some of the more compelling recent sonic developments. A creeping Hellhammer and black metal influence has also been making itself apparent for quite awhile now, too. Witness LPs by Skitsystem or Tragedy. Sweden’s Harda Tider combine characteristics of youth crew hardcore (group shouted choruses, Cro-Mag-like chord changes, and moshy breakdowns) with Scandinavian d-beat. I’m not sure if anyone used the term “blackened thrash” in the 1990s, but it’s its own veritable genre now: thrash with old school black metal, like Tyrant or the newer Darkthrone albums.

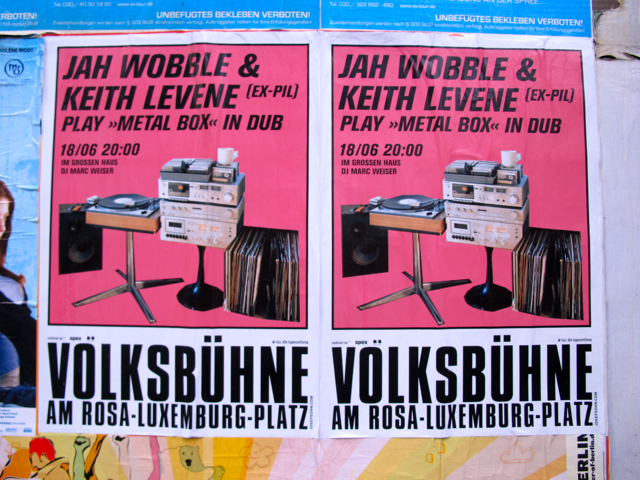

One could argue that incorporating disparate influences is old hat. And that is true. The difference nowadays is the sheer size of the sonic palette available to younger bands, thanks to the democratization of obscure punk music via blogs and the like. There is also a willingness to chip away at ossified punk strictures – what I might even dare to call punk dogma. Older punks might resent it and insist younger bands don’t “get it.” But this just reminds me of an anecdote about Minor Threat opening for PiL in Washington, DC in 1983. According to various interviews with Minor Threat members and the book Dance of Days, Minor Threat had to argue to be paid for their performance with the postpunk vets.

“We played for a pizza and a case of Coca Cola,” Ian MacKaye says. “That was our payment that night. When we came off stage, they pulled up in a limousine after us.” They never got to meet the members of PiL, even back stage. Lydon apparently thought the younger band were foolish Johnny-come-laties. (Full disclosure: I’m a fan of both PiL and Minor Threat.) The lesson here is that the person who can claim seniority isn’t necessarily the most in touch with where the culture is, or should be, going.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit