Their calling cards are umbrellas, tissue packets, and flowers. Hustling tourists at historic sites, or hawking their wares at stoplights, dark-skinned migrants, from Africa and South Asia, are a common sight in contemporary Italy. Little do visitors to the country know what these Italian-speaking foreigners signify about the country’s economy. They’re not just tourists, trying to turn a quick buck, but the top-level layer of a domestic labor force that has become increasingly international over the years.

Hailing primarily from Central and North Africa, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, such workers make up the lowest rungs of Italy’s fragile economy. Some of them are legal. An equal number are not. Regardless of their status, they share in common exceedingly low wages, and inhuman treatment, at the hands of both licensed and black market businesses.

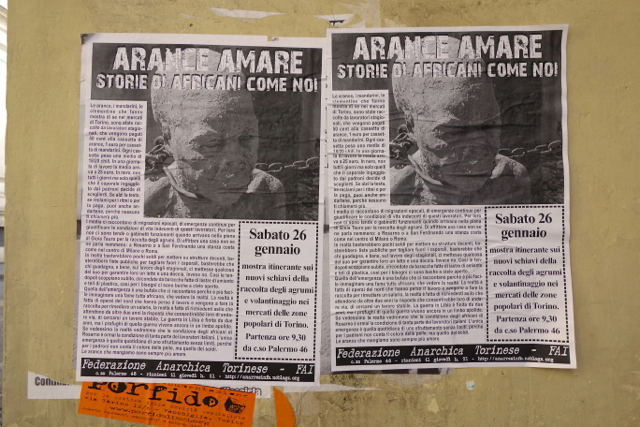

One trade in which migrant workers are especially ubiquitous is agriculture. Working seasonal harvests, in Calabrian towns such as Rosarno, African workers are especially visible, and live in appalling conditions. The Turin anarchist flyer above, entitled Bitter Oranges, narrates part of their plight. For anyone familiar with labor struggles in Italy, its disclosures will be familiar. However, with this flyer, there’s a twist. It isn’t just preoccupied with the plight of foreign workers. What it describes is the parallel exploitation of Italian workers, as though they were migrants, too. The linkage here is, in most respects, common sense. That is, if you are open to the idea that exploitation is universal, and not necessarily restricted to race, or national identity. Italians become black, and vice versa, as the logic goes. The only color that really matters, contends the flyer, is that of money.

BITTER ORANGES

Oranges, tangerines, clementines, beautifully displayed in Turin markets, have been harvested by seasonal workers, paid 50 cents for an orange crate, and 1 Euro for a tangerines crate. Each crate weighs 18/20 kilos. In one working day, the average sum reaches 25 Euros. Under the counter, and not every day, but only when the recruiter hired by the owner decides to choose you. If you raise your head, if you complain about the working pace or about the pay, you can leave as well, because no one will call you again.

Media tell us about epochal migrations and never ending-emergencies to justify workers’ indecent living conditions. No tents or functioning toilets for them when arriving at the Gioia Tauro plain for the citrus harvest. Don’t even mention renting a house. In Rosarno or San Ferdinando, a room costs as though it was in the center of Milan or Rome. Actually, little money would be enough to organize respectable structures. Public lists would be enough to exclude recruiters. It would be enough for those making the money, and a lot, for seasonal workers, to put a little of their earnings towards grant workers a bed and a shower. But no. And so, the camps quickly burst, surrounded by shacks of asbestos plates and plastic sheets; so, instead of toilets, open-air ground holes.

The emergency is a hoax, we are told, because it’s easier to imagine a totally African famine than to face (its) reality. Reality consists of Northern (Italian) factory workers who lost their jobs, and have come to harvest to get a salary; reality is made of people applying for asylum and waiting for two years (for) the answer that would allow them to move, and look for a more secure job. The Libya War ended two years ago, but the refugees from that conflict still live in stateless limbo. If we could see reality, we would see that the condition of the African workers in Rosarno has become the condition of a large part of Italian workers. The only emergency is that of daily exploitation with no limits, because for the owners, skin color doesn’t matter. The only thing that does matter is the color of money.

The oranges we eat are always more bitter.

Saturday 26 of January: Traveling exhibit about new slaves of (the) orange harvest, and flyering in Turin’s popular district markets. Start at 9.30 AM from Corso Palermo 46.

Turin Anarchist Federation: FAI

Corso Palermo: Meetings every Thursday at 9pm.

Translated from the Italian by Giulia Pace. Introduction and photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit.