Edited by Titus Hjelm, Keith Kahn-Harris, Mark LeVine, Heavy Metal Controversies and Countercultures presents a wide range of perspectives and approaches to the topic, probing the ways that race, gender, violence, and politics find expression in the wide range of instantiations of metal. The editors of this collection all have serious bona fides in the scholarly study of metal.

Kahn-Harris’s Extreme Metal: Music and Culture on the Edge (2007) provided one of the clearest analyses of the personality types and practices characteristic of extreme metal fans, cutting through the multiple layers of moral panic to discover a subculture more intent on trading obscure 7” vinyl than on sacrificing goats to the dark lord. In many ways, Mark LeVine’s Heavy Metal Islam (2008) anticipated the cultural energy that drove the Arab Spring, and its revolutionary youth politics. The collection that Kahn-Harris, Hjelm, and LeVine have assembled takes some interesting steps along the road of extending and expanding the growing scholarly literature on this topic.

One might be tempted to think that it would be easier to write about metal than punk. But while superficially metal seems to evince a greater stylistic and aesthetic unity, it does not take much scratching of the surface to reveal complex overlapping patterns of transgression, connoisseurship, and mundanity that compose the genre. Unlike its punk rock cousin, which started out as a kind of glorified art project, metal was in many respects an organic outgrowth of mainstream rock. Metal was birthed in the work of bands like Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, and (at least according to some people) Grand Funk Railroad, who stripped down the decadent and overblown rock of the late 1960s and early 1970s to its pounding, pentatonic essence.

In its heyday during the 1980s and 1990s, metal was the source of repeated moral panics. The lawsuits filed against Judas Priest and Ozzy Osbourne after fans of their music committed suicide, the formation of the Parents Music Resource Center and the congressional hearings that it set in motion, as well as the periodic spasms of concern over teen Satanism were all examples of moral panics sparked by the apparently transgressive nature of metal. There is a certain irony here since, unlike in the case of punk, there was no hard disjunction between the culture and lyrical substance of metal and the corporate institutions with which the bands became involved as they grew more popular. Where a band like The Clash had to spend time wondering if they could still sing a song like “Career Opportunities” once they actually had some, Judas Priest’s “Breakin’ the Law” made just as much sense at pretty much any point in the band’s career.

Many of the contributions to this volume address the myriad ways that the transgression of boundaries. Lee Barron’s analysis of the Pornogrind microsubculture illustrates the surprising ways that its intense and violent misogyny is in important ways the mirror image (or the confirming instance) of Andrea Dworkin’s association of pornography and violence. One the one hand, Barron’s analysis seems to suggest that there is something substantive to be concluded from the homology between Dworkin’s extreme claims about violence and sexuality and the attitudes of bands like Waco Jesus and Soldered Poon. This seems not quite apposite, given the obscurity of the subculture, but Barron’s essay does an excellent job of parsing the ways that porngrind oversteps the bounds of extremity for its own sake into being an expression of actual violent misogyny.

The relationship between metal and violence is addressed in several of the pieces, particularly those devoted to the politics and practices of the Norwegian black metal scene. This constitutes an especially interesting case, in that while many metal acts had sung about committing acts of violence, (and some had actually undertaken them) the denizens of the Norwegian black metal community actually put their ideas in to practice in ways that resulted in burned churches, dead bodies, and long jail terms. Michelle Phillipov’s contribution seeks to move beyond the well-taken criticism leveled against the purveyors of moral panic that the music and imagery of metal doesn’t generally cause people to act out. While conceding the truth of this proposition, Phillipov looks at the way that the members of the Oslo scene actually put their violent words into action. One fact highlighted by this essay is the challenge of finding new, more extreme modes of boundary challenging, which was such an important element of the culture of black metal in Norway. Yet the violence, which was so definitive of the substance of the scene when it was just five or ten guys in an unlighted record store in Oslo, was transformed by the commercial success of early scene stalwarts like Emperor and Immortal. Phillipov deftly illustrates the ways that the violence was eventually transformed into the more esoteric lyrical content of complex, serious artistic compositions.

Some of the pieces included in the volume have interesting external implications, none more so than Jeremy Wallach and Alexandra Levine’s attempt to provide a systematic description of the ways that metal scenes originate. While their presentation is at times overly schematic (viz. their insistence on the emergence of cover bands as an intermediate step between scene emergence and the formation of bands playing original compositions,) they do get to some remarkably substantial conclusions about the mechanics of scene formation. Their sketch is partly interesting given that it uses Toledo, Ohio and Jakarta as parallel cases in order to illustrate the transnational commonality of the ways that metal scenes arise. This work invite comparisons to (among other things) the origins of punk in self contained coteries, first in New York, then in London, then in Los Angeles, Washington D.C., Austin, and a range of other American cities and towns. Unlike in the case of punk, the integration of metal into the circuits of corporate promotion and distribution meant that models of music and dress were widely available. Metal records were pressed and distributed in greater numbers. Although somewhat limited by the aesthetic prejudices of the music press, metal bands had more ready access to the mainstream media, since their transgression, unlike that of early punk, didn’t involve direct critique of the economic and moral underpinnings of middle class society. When the Bad Brains’ black, dreadlocked frontman H.R. opened “Fearless Vampire Killers” by screaming, “the bourgeoisie had better watch out for me!” he was already in another league of transgression than that of the crypo-Christian lyrical stylings of Black Sabbath.

Perhaps the most interesting conclusion to be gleaned from this collection is the degree to which the culture under examination is a constantly moving target. Metal is in a constant process of transformation, spinning off new styles and subcultures and simultaneously becoming imbricated in the established culture of industrial societies while it searches for new ways to overstep boundaries of propriety and settled culture. Here again we find a similarity to the punk subculture in that there is no simple answer to what metal is, either in its stylistic or its cultural dimensions. Yet it continues to be a viable genre, reproducing itself in ever new forms and creating spaces for individual identity formation both within and beyond the grip of mainstream social norms.

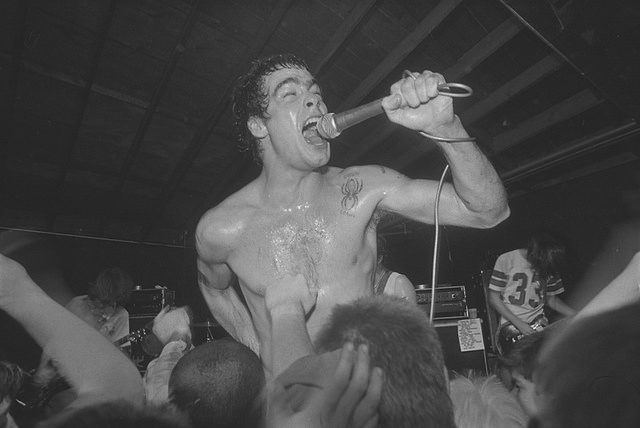

Photographs courtesy of Sean Bonner and Public Collectors. Published under a Creative Commons license.