It shouldn’t surprise anyone that a quick deal between the P5+1 powers and Iran failed to materialize. Hopes were understandably raised by the fact that the United States wanted a deal, and that Iran declared its openness to unprecedentedly intrusive inspections of its nuclear facilities. But what is at stake in these talks goes beyond the atomic issue. It deals with the entire Western approach to the Middle East.

As I explained recently, the Obama Administration has a tough task in thawing US-Iran relations, but this is what it has taken on. Indeed, across the board, in Syria, Egypt, Libya, and throughout the region, Obama has eschewed the simple route of backing the status quo and supporting long-time allies amid the changes that have begun in the region. Bahrain, where the US continues to support an oppressive regime, has been an exception. However, even there, US policies have fallen well short of the expectations of long-time ally, Saudi Arabia.

I recently spoke at some length with a high level Arab diplomat, a man I’ve known for some years and who is of a rather conservative bent. He was quite concerned about the P5+1/Iran talks in Geneva. Indeed, he was deeply troubled by them, and I understood his reasons. He is not wrong in thinking that the Arab old-guard establishment (the Gulf States, Jordan, Egypt under the new government, which is essentially the old Mubarak government) should be very concerned about the West taking its thumb off Iran. Regardless of whether Iran ever pursues a nuclear weapon, lifting the sanctions will allow them to rebuild their economy and, more importantly, enhance their status as a major player in the region. That bodes ill for the old-guard dictatorships, who see Iran as direct competition for regional influence.

Israel is a different case, of course, for a number of reasons. Its more Western orientation, its close security cooperation and abilities, the history since World War II and, of course, Israel’s powerful lobby, especially in the United States all mean that it will continue to maintain close ties to the US and Europe. But even Israel is seeing the intended shift, and its Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, is certainly preparing to do whatever he can to prevent it. Because while the EU and US are going to remain committed to Israel’s real security needs, they need not express that concern only according to Israeli desires, whims which often have no connection to security at all.

What seems to be taking place in the Obama Administration is a recalibration of US foreign policy norms in the Middle East. The shift should not be overstated, as it certainly will be. We’ll be hearing a lot more about how Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry are “abandoning our best friends and closest allies in the region.” Israel will be the featured character in that play, but Saudi Arabia will be just as important in policy circles. And the speakers will routinely be members of Congress, leaders of “mainstream Jewish groups” (which represent an increasingly small minority of zealous nationalist Jews) and a few fiery Christian Zionist “pastors.”

On the other side, there will be those who will downplay the shift, noting that the US will continue to stand behind Israel and Saudi Arabia. That camp, mostly from the left, and some from the old-guard conservatives, labors under the belief that US policy is fully “dictated” by Israel (in some variations, it is also Saudi oil interests,) failing to acknowledge a long history of commonality, friendship and common cause between the two countries. Not to mention, of course, a lot of lucrative weapons development contracts, and civilian business cooperation, that have deepened already strong strategic ties between Jerusalem and Riyadh, and their American ally.

Both camps will be wrong. The United States will continue to safeguard Israeli security and they will continue to support Saudi Arabia militarily. What the Obama Administration is trying to do is to reorient US policy in the Middle East so it is less subject to the whims of its closest regional allies.

This is not some great change of heart in Washington. The George W. Bush Administration, whose foreign policy was dominated by neoconservative extremist thinking, was anomalous in its willingness, even eagerness, to engage US troops directly in the Middle East. The elimination of Saddam Hussein’s regime led to a massive sectarian conflict that spread throughout the region, but it also eradicated the dual containment system that held the spread of Iranian influence in check. Given that this was a purely US decision, it is not surprising or unreasonable that our allies in the Gulf region expected the Americans to maintain a more direct involvement, using its massive military might to continue to deter Iran and help our allies pursue their ends in the widening sectarian conflicts taking place in the Middle East.

The United States has been dancing on the edge of war with Iran for a decade, ever since Iran was admitted into the exclusive “axis of evil” and was declared a target by more than a few neocons. The nuclear standoff in recent years raised the tension level and created a much stronger possibility of the US being drawn into a war it didn’t want. With both Saudi Arabia and Israel pushing the US to attack Syria, the danger of escalating American military involvement in the region certainly called for a realignment of US regional policy.

The opening created with Iran on the nuclear issue offered the possibility of not only resolving that crisis, but also facilitating dialogue with Tehran. Both Israel and the Saudis know that, at least in the short term, the US is not going to abandon their interests for the sake of a warm relationship with the Iranians. But a real thaw in US-Iran relations, on terms that are respectable for both sides, would mean significantly increased opportunities for its government to enhance Iran’s standing as a player in the region. Where that relationship might go in the future is anyone’s guess.

Ultimately, this is what the Saudis, the Emirates and the Israelis all fear. The Gulf monarchies are concerned because the United States has shown decreasing resolve in protecting existing dictatorships. Increased Iranian influence could strengthen popular determination in their countries. Israel is concerned that without the Iranian bogeyman (and despite the fact that increased US-Iran détente would likely mean more restraint on Hezbollah, and on Iranian anti-Israel activities and rhetoric,) with a diminished US presence in the region, the pressure to come to terms with the Palestinians will be irresistible. Indeed, Iran would probably shift its pro-Palestinian strategy from anti-Zionist rhetoric to diplomatic appeals and activism. All of this is highly distressing to the nationalist politicians like Naftali Bennett and the newly-reinstated Avigdor Lieberman. Even more so to the Likud, and its neoconservative darling, Netanyahu.

Such a path will open up many options for the United States. It would still protect its Israeli and Saudi allies militarily and safeguard the flow of oil from the region. But it could do so while taking into account the desires of its closest allies rather than having to tailor its policy toward those desires. In the end, it is likely a much better scenario for the US. The question is will it happen?

Right now, the smart money would have to bet against it. France, which remains oriented toward an interventionist foreign policy (ironic, considering the animosity their previous policy under Jacques Chirac generated in the United States a decade ago) worked to scuttle a preliminary deal with Iran, and seems to generally support the Saudi and Israeli goals of maintaining tensions with Iran. The United States cannot simply ignore a fellow member of the P5+1, not to mention the UN Security Council. But while some parts of the French foreign policy bureaucracy echo some of the American neoconservatives, France is ultimately interested in resolving the nuclear issue and increasing regional stability. They can be brought around if the United States is committed to this path.

More importantly, perhaps, Congress remains firmly devoted to a foreign policy based on Israeli views and desires. The incessant lobbying by AIPAC and other groups who seem far less interested in Israeli security than in keeping Bibi in his happy war footing has a great deal to do with this. But this is about a lot more than campaign contributions and lobbying.

Israel has always had its zealous supporters in Washington, those who believe that the US must support Israeli policies at all costs, whether because they feel the Jewish state is owed such fealty because of the will of God and prophecy, the history of anti-Semitism, the memory of Israel’s usefulness in the Cold War, Israel’s common values (which are very real) with the US, or simply because they don’t understand foreign policy and this is the simplest course. Those zealots appear in both parties, although there are far more of them among the Republicans. They don’t need AIPAC to tell them which way to vote on Middle Eastern matters. And Israel is moving quickly to activate them.

The level of bellicosity out of Israel is unprecedented. Even Yitzhak Shamir, when he was feuding with George Bush Sr, did not send out such provocative messages as we’ve seen, both directly and indirectly, from the Israeli government, directed at a US President and Secretary of State. Congress is gearing up to fight Obama hard on the Iran negotiations, and members of Obama’s own party are leading the charge.

The biggest losers, as always, are the Palestinians. The peace talks have been exposed as a joke by the fact that the Palestinian negotiating team quit, but no matter, the talks will go on, because, after all, of what importance are the negotiators when the only point is to talk? If rumors of an American bridging proposal slated to be brought out in January are true, it is almost certain that the purpose will be to use that as a bargaining chip to get Netanyahu to back off of his anti-negotiations stance regarding Iran in exchange for the US dropping their plan.

The Iran issue, as well as the Syrian civil war, the ongoing restlessness in Egypt, continuing instability in Iraq…all of these combine to push the Palestinian issue farther into the background than it has been at any time since the late 1970s in the Arab world and on the global diplomatic stage. While a peace deal is still very much desired, it simply isn’t as pressing as these other issues at the moment. Given Israel’s determination to expand settlements far and wide, and the ongoing inability of the Palestinian political system to coalesce around a unified leadership, there is no hope for a resolution at this time.

Still, I’m prepared to believe that the Obama Administration is doing very much the right thing here. Yes, these talks will fail, but that was inevitable long before they began. Oslo is dead, Israel’s government is more obstinate than ever, and the Palestinian “leadership” is a dysfunctional joke. But Israel has also burned a lot of bridges with the White House and, more importantly, with Brussels. And it’s making that situation worse with every passing day of bellicosity, and every attempt to bring a cataclysmic war to the region. That’s something the West is desperately trying to avoid.

In the US, Israel is likely going to win this battle, but it may well lose the war as a result. The American people want a diplomatic resolution with Iran. If Israel’s lobby in Washington scuttles it, as seems to be their intent, this will expose them as AIPAC has never been exposed in the past. Because Netanyahu has been so abrasive, the Lobby is really all he will have left when the smoke clears. Americans noticed that Bibi was trying to push us into an attack on Syria which almost no one here wanted. They are noticing that his government is trying to push us closer to war with Iran, something Americans also don’t want. The US public remains committed to Israel’s survival, but not to its policies and not to its occupation. Yet, Netanyahu is pushing that ambivalence to the forefront, oblivious to the consequences of his behavior.

That’s not enough, in the long run. As we saw with Syria, the Lobby is impotent when trying to brazenly act against the overwhelming views of the US public. It has the power it does, in the last analysis, not because of campaign contributions, but because Israel has historically been embraced by the American people. That embrace is becoming more conditional, and is weakening popular support Israeli policies.

The times are changing. They may not change soon enough to stop Congress from scuttling a peace deal with Iran. But by the time they do change, perhaps the repercussions from Israeli expansionism, already obvious in Israel’s capitulation on the matter of the EU’s new guidelines against working on projects involving the settlements, will have changed things domestically, in Israel. Perhaps by then the repercussions of the failure of Palestine’s leaders to unite and make any real headway in freeing their people from occupation will have brought about a new, smarter, bolder leadership. These days might not be far off now.

And, perhaps, Obama will win this battle and get his nuclear deal with Iran. The odds are not great, but it’s also far from impossible. If that happens, some of those changes in Israel-Palestine and others in the region might be accelerated. Either way, Obama is trying to change the nature of US Middle East policy. If he does it well enough, his successor may not be able or, perhaps, even interested in changing it back.

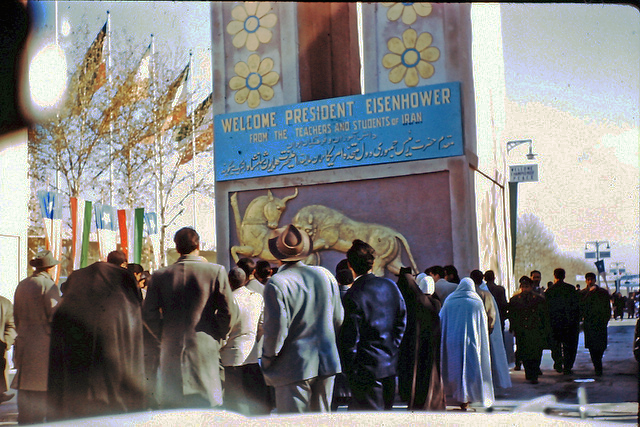

Photographs courtesy of cramsay. Published under a Creative Commons license.