Anyone who travels to Pakistan, or Yemen, for long periods, is confronted with violence. Death is everywhere. One of the ways I have come to terms with it is through re-watching relevant films, in particular, A Serious Man.

From its ruthless portrayal of suburban ennui, to the generational conflicts that defined American Jews during the 1960s, it’s a densely and complicated story. I was most most moved by its portrayal of how two very different Jews ultimately learn to deal with death: the analytical Larry Gopnick, and his more psychedelic son, Danny.

A Serious Man centers on Larry’s struggles to understand the various problems that are suddenly forcing themselves into his life. Why is his wife divorcing him? Why is the tenure committee suddenly receiving letters that are denigrating him? Did his ESL student attempt to bribe him? Is his brother a mathematical genius, or simply losing grip on reality? Did his wife have an affair with the gently condescending Saul, or not? Why does everything seem like it’s falling apart?

Larry seeks out the opinions of three separate rabbis to get answers. Given his Job-like circumstances, you can understand why. Considering the crises he’s dealing with, he feels singled out, as though fate, in a religious manner, has conspired against him. Did he do something to deserve this?

It’s no coincidence that Larry is a physics professor. Physics allow him to have some sense of control. He is operating in a modern setting where educated men like him are used to being able to ultimately subject confusing events to science. As Larry says to an ESL student, stories like Schrodinger’s Cat don’t matter. They are fables, meant to add clarity to the real stage: numbers, and formulas.

The problem is that not everything can be rationalized. When he asks the first two rabbis for advice, they give him abstractions: one about how he should seek Hashem (God) in a parking lot, and another with a long story about seeing numerology in a patient’s teeth, that ultimately has no ending. The third rabbi simply doesn’t see him, making Larry feel impotent in his search for truth. But that’s the point: there isn’t an answer for everything. Larry expects mathematical certainty out of situations that could have a thousand different

explanations.

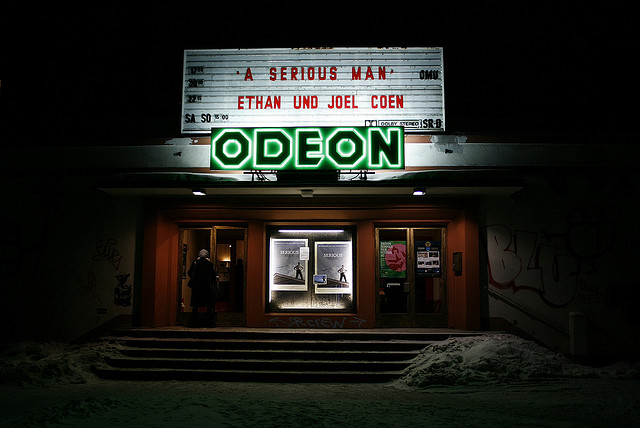

A Serious Man: opening scene from Anton Nossik on Vimeo.

Larry is oblivious to the fact that his son Danny gets it. Danny never says this explicitly, mainly because he is a kid who just wants to get stoned and watch F Troop. But here is where I see the importance of Somebody to Love, the Jefferson Airplane song which serves as the film’s soundtrack signifier. It bridges the movie’s Yiddish-language beginning, which worries about the existence of evil (a dybbuk) with Danny hearing the call of assimilation, of American culture.

Other reviewers have noted differently, that this is likely meant to link the psychedelic counterculture of the Summer of Love with the type of Jewish mysticism that causes Larry so much anxiety. Indeed, Larry is so attached to numerical certainty that he overlooks the core of religious practice: to embrace mortality by accepting what cannot be understood. Yet, at the film’s end, when Larry is told that he has cancer, it’s clear he is still asking himself why.

Danny is intermittently chased by a bully who wants his money back. During the sequences, the bully is seen coming closer, and closer, before Danny ultimately reaches his house, and locks the door. With each sequence, the bully gets closer. His face is never seen. This scene could mean anything. Is the house Zion? Is the bully Hashem?

Accepting death means doing what Danny does at the end of the film, when he tells the bully that he has his money, and we see the boy’s face for the first time. It’s locked into a grin. Danny gazes into a rapidly approaching tornado that could kill him. Instead of being afraid, however, he is struck with awe. It’s an awkward moment, surely, not without its own element of irony. It’s the Coen Brothers, after all. Not exactly proponents of spirituality.

I’d like to think that that this was a good sign, though. That somehow, Danny had lowered his guard long enough to accept the inevitable, because he’d learned see to the other side. It wasn’t a dybbuk that was coming to claim him. It was just a tornado. In learning to accept death for what it is, he’d finally arrived. In his own life, in America, the works.

Photograph courtesy of Alessio Trerotoli. Published under a Creative Commons License.