It’s hard not to discuss films that have already appeared on critics’ lists. However, most of what we read about in year end favourites like this still elude the majority of moviegoers. Most are unable to attend festivals, and don’t live in major cities, where end-of-year theatrical releases ensures eligibility for major film awards. For such persons, annual picks, however many of them we can read, are essential. Here are mine.

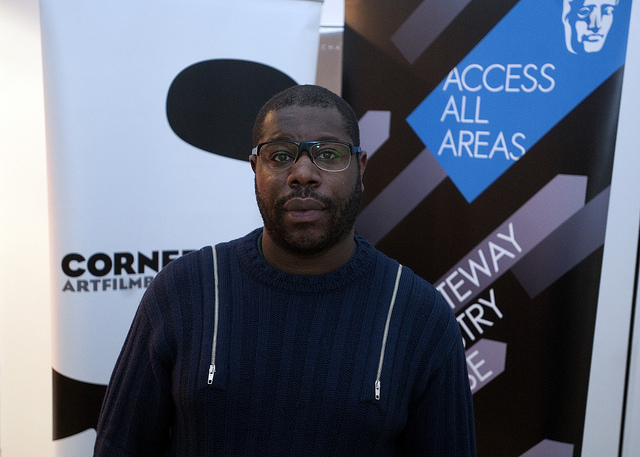

12 Years a Slave (Steve McQueen): On almost everyone’s list I suspect it would have been on mine. However, despite the British provenance of its star, Chiwetel Ejiofor and its director, Steve McQueen, the film will not appear in these parts until January 2014. Given the ‘local’ love and support of filmgoers like me, who eagerly purchased our tickets to Hunger (2008) and Shame (2011,) I feel a bit miffed, but look forward to the film nonetheless.

American Hustle (David O. Russell): I have to rein in my outrage here. Russell owes us (in the UK) nothing, and fortunately, it awaits me next week, when it’s too late to make this list.

And now to those I did see:

Film whose place on the best lists I heartily endorse: Spring Breakers (Harmony Korine.) The gleeful crime spree of a film that fuses the bright colours of an ostensibly innocent ritual with the grotesque makes it a hilarious pleasure. Some might find the cultural critique canned or old. Perhaps it is, but the delivery revels in an outlandish and perverse jouissance. I want James Franco to be nominated for an Academy Award for his performance as Alien. And I want to the clip played at the ceremonies to be this one. Constant y’all.

Best performance by a cat: Inside Llewyn Davis (Joel and Ethan Coen.) Actually, there are many cool cats in this film about a folksinger navigating his way through the 1961 folk scene, especially Oscar Isaacs in the title role. Criticized for its virtual unrecognizability and absence of camaraderie, that may not be the point as the film seems more preoccupied with the dark humanism that that characterised A Serious Man (2009.) I’d also argue that this one feels similarly Jewish, although I can’t back that up right now. And despite coming from StudioCanal, the film feels more believably American than the ethnographic other of Nebraska (Alexander Payne.)

Best performance by videotape: Computer Chess (Andrew Bujalski.) Nostalgia suffuses this film, set during a computer chess tournament in the 1980s. This is due to a range of factors, from costume and dialogue to the use of a vintage Sony Tube Video Camera. The result is a register that imbues Computer Class with a touching softness and instability that enhances a story about the combination of humanity and technology.

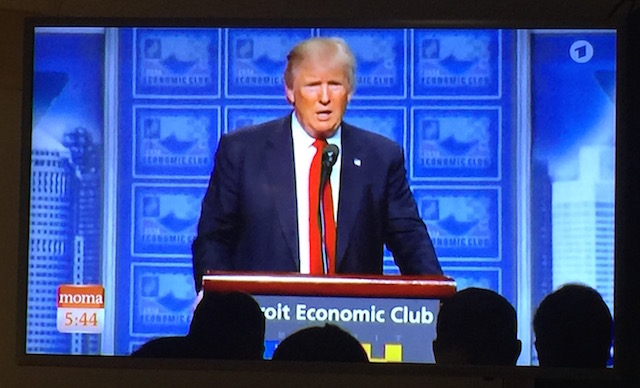

First Runner Up: No (Pablo Larrain.) Here video is employed in the story of the ‘No’ campaign in Chile’s 1988 referendum, on whether Augusto Pinochet should retain permanent power. The use of video and its visible degradation illustrates not only the conflation of entertainment and politics, but also the ways in which historical films rely on media for their own authenticity and agenda. Warning: the song is an earworm.

Filmmaker who joins my list of those whose works will always merit a look (I suppose I could just write ‘One to Watch’ but… No): Ben Wheatley. There are filmmakers whose latest I must view, regardless of any reports. With the Sightseers and A Field in England, Wheatley has joined that list. The former offers a darkly comic English ethnography of sorts, as a pair of lovers travel through the North, visiting such sites as the National Tramway Museum, and the Pencil Museum in Keswick whilst killing a bit on the side. The latter is something of a psychedelic thriller set during the Civil War. It merits far more than I can say here—not because I am limited for space, but because I really must watch it again.

Criminally overlooked (in year end lists): The Selfish Giant (Clio Barnard.) The director of the exquisite verbatim theatre documentary, The Arbor (2010) has moved seemingly effortlessly into fiction. The Selfish Giant provides a Kes (1969) for the present day in the story of two boys living on the estates of Bradford and scavenging for bits of metal to sell to the local scrapyard. Although social realism has potential to go relentlessly grim, this film is suffused with humanity and spirit, the latter of which is enhanced considerably by the rambunctious and foul-mouthed Arbor (Connor Chapman in a fabulous performance.)

Speaking of child actors and performances: Waad Mohammed was a delight to watch as the enterprising and spirited titular Wadjda (Haifaa Al-Mansour,) who wants a bike (despite all warnings of the inevitable dangers to her ovaries) and will do everything in her power to secure one. That power, of course, is shown to be limited and hamstrung by the conventions that constrain women’s freedom, especially the freedom to travel. (Her mother is entirely dependent on a driver to take her to work, a several hour commute.) The sense of determination and achievement onscreen has an offscreen corollary: shot on location in Riyadh, this is the first film made in Saudi Arabia by a female director.

Not to exoticise or ghettoise with a patronising ‘well-done’ but let’s hear it for more unexpected female directors: Fill The Void, directed by Rama Burstein, an extreme Orthodox woman, grants a glimpse into the Haredi community. It is an intimate and moving film about a girl pressured by her parents to marry her widowed brother-in-law in order to ensure he stays in the country along with his son. Emotionally complicated, this is not a film that seeks to criticize the workings of this community. Indeed, it aims to show the degree of autonomy held, as all hinges on its protagonist’s decision and her willing participation in the arrangement. The film also distinguishes itself for being one of the few films about the Jewish Ultra-Orthodox that does not explore the divide between the secular world and the traditional one. As viewers, we stay enclosed in this traditional and intimate space, the tight shots enhancing the perception of this enclosed world.

Because Romanian Cinema: Pozitia copilului/Child’s Pose (Calin Peter Netzer) and Dupa dealuri/Beyond the Hills (Cristian Mungu.) This is a national cinema that seems to move from strength to strength with its festival-destined output. In the former film, the stellar Luminita Gheorgiu, plays an affluent woman seeking to control her son’s life by managing the fallout from his car accident and resulting manslaughter charges. The intimate, the institutional and the social collide in this fine drama. In the latter film, the director of 4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days once again explores women’s relationships and attends to process rather than event: in this case a slow exorcism.

Best series: Although The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (Francis Lawrence) and The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (Peter Jackson) have both enjoyed praise this year, I speak of something perhaps a bit quieter, but no less forceful: Ulrich Seidl’s Paradise Trilogy (Paradies: Liebe/Paradise: Love, Paradies: Glaube/Paradise: Faith, and Paradies: Hoffnung/Paradise: Hope,) three films about three women (a mother, an aunt, and the daughter) and their respective holidays. In his strangely detached yet humanistic way, he takes us from brutal depiction of the international political economy of bodies in German sexual tourism in Kenya, through a conflicted domestic pilgrimage, to a surprisingly gentle and touching story set in a fat camp.

Films that took advantage of cinematic potential to provide new ways of telling stories: It’s Such a Beautiful Day (Don Hertzfeld), Upstream Color (Shane Carruth), and Museum Hours (Jem Cohen). If I begin writing about any of these films, I might never stop. These all have, however, pushed at the boundaries of film to provide haunting, hypnotic, and deeply moving stories.

Three films on everyone’s lists that are excellent, and yet leave me slightly ambivalent:

La Vie D’Adèle/Blue is the Warmest Color: The intimate and passionate love story set predominantly in the interstices and the mundane was compelling. I am a great fan of the director, Abdellatif Kechiche, whose Vénus Noire, the story of Saartjes Baartman or the Hottentot Venus, was gutting and unforgettable, providing an unrelenting look into her life subjected to the colonial gaze, from ethnographic displays, to sex shows to the autopsy. The voyeurism in that film worked to great effect, implicating the cinema audience in the pernicious apparatus. In Blue, however, the voyeurism seems less reflexive and more fetishizing, particularly in the notorious sex scene, which despite its silliness, conveys little intimacy or realism or even a bodily mundane—possibly because despite all, the bodies seem posed for the benefit the viewer. The fetishizing aspect is granted a mouthpiece by the male party guest, who expounds at length on the mysticism of female sexuality.

Stories We Tell (Sarah Polley): This is a lovely and thoughtful documentary about a family’s secret, and the way all histories, official, personal, and cinematic, are composed of multiple perspectives, fantasies, and truths. The film implicates itself in the use of re-enacted footage, but Polley protects herself somewhat behind the camera. Perhaps that reflexive depiction is intended to characterise her own limitations, but it still feels more like hiding. Perhaps a bit too neat for a story about the challenges of family and storytelling.

The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer): There is absolutely no question that this film (along with Leviathan [Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel]) is one of the most important documentaries made this year and whose relevance will persist long past awards season. It is stunning to watch, both for its subject matter—genocidaires making a film about their mass slaughter using all the genres available to these gangster cinephiles—and for its form. It is uncomfortably beautiful. It is discomfiting, and that is a good thing when taking on the topics of impunity, history, violence, and its representation. And yet I can’t help but feel a false resolution is provided in the retching Anwar Congo. Some have read this as his own cathartic moment—the reenactments bringing some kind of recognition and justice. However, I read this as his performance of what he expects from this kind of genre—from films that demand redemption from their main characters. The question is whether the film and filmmaker have granted him, and the audience, this comfort, or whether it has signalled the irony strongly enough to ensure the complexity and perpetual discomfort. I will be watching this again, though. Many times.

Best thing in DVD releases: This year saw the long-awaited and highly celebrated release of Chronique d’un été/ Chronicle of a Summer (Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin, 1961,) which was given the Criterion treatment, complete with restoration, updated subtitles, archival interviews, an interview with anthropologist Faye Ginsburg, and the documentary Un été + 50, which includes outtakes from the film, as well as interviews with some of the subjects in the present day. An ethnography of Parisians in the summer of 1960, Chronicle is a glorious film that explores the power of traumatic memory, the presence of politics, and the challenges we face when telling our stories in news media, film, history, sociology, and anthropology. Indeed, this is a film whose penultimate scene offers its own characters reflecting on the film we have ostensibly seen until that point, questioning the truth of the images, and even of their own performances.

First Runner-Up: A refurbished version of Le Joli Mai (Chris Marker, Pierre Lhomme, 1963) was also made available this year. This film, based on Chronicle’s exploration of a city gives something more of a vox pop portrait and with an attention to politics (decolonisation, economic injustice) that feel relevant for today. Also relevant: the presence of cats, whether as interstitials for a political argument or appearing in costumes. But one would expect nothing less from Marker, the great friend to cats.

Other films that have stayed with me or which merit mention, but which I won’t write about here:

Crystal Fairy & The Magical Cactus and 2012 (Sebastián Silva)

What Richard Did (Lenny Abrahamson)

Le passé/The Past (Asghar Farhadi)

A perdre La Raison/Our Children (Joachim Lafosse)

The Ballad of Genesis and Lady Jaye (Marie Losier, 2011)

Edited to Add:

Film I just caught under the wire and belongs on all ‘best’ lists: Frutivale Station (Ryan Coogler.) Coogler dramatises the last day in the life of Oscar Grant (an excellent Michael B. Jordan) by focussing on the mundane details leading up to the tragic shooting. To say the observational approach puts a ‘human-face’ on real-life events almost limits its possibilities. Because the film opens with the shooting, the threat courses throughout the film, a reminder of the danger that faces all African-American men, no matter who they are. Indeed, there is no sanctification of Grant or of any of the characters; the film is human to its core, which provides both its appeal and its power.

Film I most anticipate in 2014: The Congress (Ari Folman)

Screenshots courtesy of Cornerhouse, Rama Burstein and Harmony Korine. All Rights Reserved.