Seeking rationality in punditry on foreign policy is a fool’s errand in the best of times. Bombastic statements and ideological polemics are the rule of the field. But when the United States and European Union are facing off against Russia, it is worthwhile to demand some clarity and, yes, even honesty. These have been in short supply on both sides.

We can see the absurdity stemming from political leaders. Vladimir Putin’s assertion that there were no Russian troops in Ukraine when they were plainly there for all to see was nicely matched by some truly Orwellian rhetoric from the United States. The finest example was probably Secretary of State John Kerry when he said “You just don’t in the 21st century behave in 19th century fashion by invading another country on completely trumped up pre-text.” Yes, this is the same man who couldn’t contain his enthusiasm for the invasion of Iraq and who, after the pretext everyone knew was false to begin with was proven to be so, said he would have still voted for the war. I wish I could have seen just one Iraqi’s face when she heard Kerry’s criticism of Russia.

But Kerry’s statement, aside from its blatant hypocrisy, illustrates one of the major problems that go beyond the usual political rhetoric and infect the zeitgeist around this issue. It is one thing when we do something like invade another country for whatever interests we are trying to protect, real or imagined. But when rivals, let alone enemies do so, they are showing their nefarious nature, their eagerness for world domination.

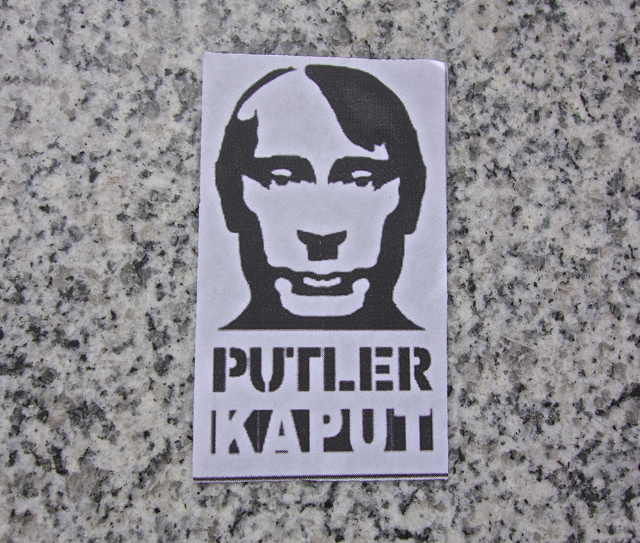

This has been the prevailing portrayal of events in the Ukraine, where Europe and theUS are the shining lights of virtue and Russia, especially its leader, Vladimir Putin, are the newest incarnation of evil. It didn’t take long for one hawkish Democrat with her eye on the White House in 2016, Hillary Clinton, to compare Putin’s actions in Ukraine with Adolph Hitler’s in Poland. The comparison is not just bombastic: it fails on the basic facts of the situation. While some certainly saw Hillary’s comparison as an overstatement, few understood it as being completely out of line with reality, which it was.

Very little energy has been expended, either in media or in diplomacy, to acknowledge that, whether or not Russia’s actions here were justified or legal, they were motivated by concerns that the US or EU would certainly share if they were in Russia’s position. It’s easier to portray Putin as a “thug” a “Hitler” or a madman. This, despite pretty clear evidence that Putin had very real reason for concern.

I need to reiterate this, because it becomes such a contentious point in media discourse: whether defending Russian interests justified Putin’s actions or not, understanding their legitimate concerns is crucial for avoiding calamity in Ukraine and the surrounding region. The attempt to understand and recognize those concerns do not necessarily make one an apologist, nor does it imply either justification or condemnation of those actions.

One leading American expert on Russia, Professor Stephen F. Cohen, has been trying to combat the demonization of Putin since long before the Ukraine crisis, and is regularly attacked as an “apologist” for the Russian leader. The attacks on Cohen are unfair and are based on this formulation of the US/EU as the heroes and Russia as the villain; easy roles to cast even nearly a quarter century after the end of the Cold War. But Cohen, while not an apologist, does fall into a similar trap in his eagerness to paint Putin in a more realistic light. He glosses over Putin’s authoritarianism, his repressive policies and the regressive, intolerant gender agenda he pursues.

One can, as it turns out, understand that Russia falls short of the mark in its treatment of individual rights, of women, certainly of LGBT folks, of the press, indeed of democracy, and still view its actions in terms of pursuing its national interests in the same way the United States, European Union, Iran, Israel,and any other country generally do. And that is the case with Putin. When Cohen glibly points out that 85% of Russians think homosexuality is a disease or a choice, he is offering a useless and pointless defense of Putin, which undermines his more important points. Russia de-criminalized homosexuality two decades ago, and if the culture has lagged far behind the West in coming to terms with LGBT rights, that doesn’t mean that their leader has to back laws criminalizing education on the topic with rhetoric that was sure to encourage hatred of LGBT persons. The LGBT community is global and has every right to call Putin on this fomenting of homophobia.

But if Cohen is off-base in his downplaying of such attitudes (he does not by any means defend it), he hits the mark in much of his analysis of Russia’s current actions. “My main point is that we, not Putin, have managed to move the divide of the new Cold War from Berlin, where it was semi-safe, right to Russia’s borders,” Cohen told Newsweek. “Maybe it’s not an iron curtain, but divided Berlin was the divide for 45 years. Now we’ve moved it right plunk to a divided Ukraine.”

This would seem self-evident if one simply examines post-Cold War, even late-Cold War history and looks at a map. The expansion of NATO and with it, the sphere of US influence in Europe and into Asia, has been a major agenda item for decades. An initially acquiescent Russia helped that process along, but when the bottom dropped out of Boris Yeltsin’s westernization program and devastated the country in every way, Putin stepped in and changed Russia’s course. One doesn’t expect Washington, London or Brussels to be happy about that, but one does expect that they will have the experience and understanding of international relations to see it in its proper context. One expects them to understand that a great many Russian oil and gas pipelines run through Ukraine and the Black Sea access Crimea affords is indispensable. These are real and very significant interests, whether or not they justify Putin’s recent decisions.

So how do we read the actions of Russia, the US and the EU? Before I read Cohen’s interview, I brought up a similar comparison about the situation in Ukraine as Cohen does. In arguing with a former key figure in the US intelligence service on this issue last week, I asked what he thought we would do if Russia or China was working to support a change of government in Mexico in order to get new leaders who would pull that country into cooperation with them rather than the United States. Would our response be so different? The evidence of our history suggests we might have been more aggressive than Putin, but less successful.

In the West, we need to examine how we’ve responded to this issue. Back in early February, Russia leaked a phone conversation between US Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and the US Ambassador to Ukraine, Geoffrey Pyatt. That call made it clear that the United States and the European Union were deeply involved in stoking opposition to Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. Again, this is part of the way things work, but another part is that we would expect Russia to react strongly to such meddling.

But where did the public discourse go when the phone call was released? First it focused on Nuland’s saying “Fuck the EU.” An insult and an awkward moment to be sure, but hardly earth-shaking stuff; that part of the episode should have been fodder for humor more than anything else. Then there was criticism of Russia for releasing this intercepted communication. Apparently, the NSA was jealous of Russia’s publicity. More seriously, it is hardly the first time such leaks have happened as a way to expose a rival’s actions for political gain. Surely the revelation is far less worthy of criticism than the actions it exposed.

But there was precious little debate about what the US and EU were doing monkeying about so deeply in internal Ukrainian politics, much less whether or not that was a good idea. Such maneuvering was bound to bring counter-moves from Putin, and it’s worth noting that our machinations have not, historically, always worked out as we’d hoped. But our discourse didn’t go anywhere near such obvious discussions.

Putin, of course, has an easier job with the domestic press, which he can muffle fairly effectively. Still, while he may face little backlash at home for claiming that the Russian soldiers we are all watching in Ukraine were not Russian soldiers, that doesn’t play in the West, and how it plays here does matter if there is to be a decent outcome to all of this. Putin has an interest in this. He cares about being able to work with the United States and Europe on major issues as a partner, not always an adversary. The soldiers in Crimea have, at least in significant measure, mobilized from bases Russia already had there, so the Russian leader might have considered a more elegant dissembling by simply stating that fact. That wouldn’t make a big difference diplomatically, but his choice to so blatantly lie helps contribute to the “toxic media atmosphere” Cohen discussed.

In the US and EU, we must understand that this is not Hitler trying to conquer all of Europe for the empire of the Fatherland. This was Putin trying to ensure that access to pipelines and shipping as well as the markets between Ukraine and Russia were protected, while also trying to prevent having NATO on Russia’s doorstep.

Crimea as part of Russia is a fait accompli by now. And it’s hardly the first time we’ve seen part of an eastern European country secede. The US facilitated such an event in supporting the Kosovo Liberation Army in the 1990s and, at the time, we made it clear that we would support Kosovo whether it wanted independence, autonomy or unification with Albania. It is a region far from settled, but certainly the secession didn’t lead to an expanded conflict. For the most part, Serbia has reconciled itself to Kosovo’s independence.

Putin, for his part, needs to understand that this sort of juggling of territory is not easily tolerated any longer. He needs to be clear that there are similar territorial disputes all over the world and that the Western powers, among many others, do not wish to see Crimea as a precedent for more redrawing of maps in the region. Such events are rarely as bloodless as Crimea has been so far, but they are often just as potentially explosive.

Russia has re-established itself as a key player under Putin, albeit not on the level of the old Soviet Union. He has been a key force in promoting shared interests with the West in the past year, pulling Obama’s fat out of the fire in Syria and helping to push Iran to the table on the nuclear issue. He has also worked with the US on Afghanistan. These are mutual interests and, in the cases of Iran and Afghanistan, they have been put in jeopardy over the Crimea standoff.

Diplomacy must reign here. These are issues that can be resolved, especially now that Ukraine has essentially surrendered Crimea and Putin has vowed that he has no further territorial ambitions in Ukraine. No one in the West, of course, takes him at his word, nor should they. That is the role of diplomacy, to put in place the mechanisms that ensure that such promises are kept.

But a key step is to stem the tidal wave of rhetoric. Cutting out the Hitler comparisons and the image of Putin as a gangland boss would be a good start. It counters the absurd notion that Putin only acted in Ukraine because Obama is “weak,” and it allows Western diplomats to pursue more rational solutions. Obama’s statement that the US is not planning a military response to Russia’s actions was good move in this regard.

Academic David Kearn, one of the few level-headed voices to speak up on this issue in the US, suggested that “…any permanent diplomatic settlement between Russia and the West on Ukraine will likely involve some limits (perhaps formal) on future NATO expansion. Guarantees to forego Ukrainian or Georgian accession to the alliance may be necessary to adequately address Russian fears concerning Ukraine’s foreign policy under more liberal, European-leaning leaders. In return, perhaps Ukrainian ties to the EU could be strengthened without interference from Moscow.” Something along these lines is what is needed, and it starts with putting the Cold War fear mongering back in with the mothballs where it belongs.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit, Wayne Marshall, Manuel Faisco, volna80, and Charlotte Powel. Published under a Creative Commons License.