“So we’re not ‘against’ these people, and ‘for’ these other people. What are we really ‘for’? A more just political formation, one that would allow for equality at the level of citizenship,” Judith Butler concludes the second part of her conversation with Mark LeVine. “Religion may be extremely important, but I don’t think it should be a prerequisite for citizenship, and certainly not there.”

If you want to understand what makes the philosopher such a controversial figure, it is precisely such common sense, liberal-sounding, albeit American ideas as these. Civil rights and social equality take precedence over religious identity. Yet, it is precisely Butler’s insistence on such values that sets her apart, in an Israeli context, where these relations are, at various levels, reversed.

That such ideas are controversial, outside the Middle East, is of course deplorable, though, obviously, they should be in Israel, as well. Still, Diaspora attacks on Butler attests to the dangers inherent in supporting such a politics from afar. Americans are not only implicated in the Israeli-Palestinian crisis. They also make it plausible to imagine the return of such ideologies to mainstream politics in the West.

ML: Right now I’m thinking of Hannah Arendt. Gershom Scholem once criticized her for not “loving Israel” (Ahavat Israel). I remember you also wrote about Primo Levi who was accused of being ‘cold-hearted’ for taking a powerful stand against the 1982 invasion of Lebanon, and particularly the Sabra and Shatila massacres. There are these few figures who refuse to be drawn into a Zionist master narrative, but it seems that for most of us, it remains very difficult to be that ‘cold hearted’?

JB: It’s true that Gershom Scholem accused Hannah Arendt of “lacking love” for the Jews. He said, “You have no love of the people.” She replied, “I have never in my life ‘loved’ any people or collective… The only kind of love I know of and believe in is the love of persons.” She also said something peculiar, which is that she doesn’t want to love any part of herself. It has to be something different from her. I think she was trying to say that maybe there’s a form of love that’s not narcissism, and that’s the kind of love she prefers.

ML: That sounds like Levinas’ idea that you have to focus on absolute respect for the other.

JB: Yes, absolutely. This violates some of the most basic principles guiding academic inquiry. In fact, a publisher could reject your book, for example, if it did not have a strong normative claim. But, if, suddenly, taking a political view is un-academic, then indeed whole dimensions of political science, political theory, sociology, critical theory, any of a number of academic inquiries that depends on strong normative claims – philosophy itself – would be undermined. It doesn’t even make sense as an academic argument. But it obviously casts aspersion on those who take certain strong political views – not all political views – and makes them seem illegitimate.

ML: Let’s not just focus on Israel. There’s gay and lesbian studies, ethnic studies – the whole Horowitz hit list. Is there a link between the assault on so-called “radical” disciplines and the larger wasting away of academic freedom in this country?

JB: I think it’s a really good question and can work both ways. I think there are people who can defend women’s studies, gay and lesbian studies, African- American studies, but they get more worried when it becomes a question of post-colonial studies or scholarship critical of Israel. So I actually see there to be fissures in the liberal defense of progressive academic inquiry. They have a limit that they won’t go beyond. I’m not sure they have a justification for it. It’s not thought through. It’s kind of strange.

ML: Is it because in so many ways we remain a colonial country, with unresolved issues concerning the native peoples we mostly exterminated? Forget about our current imperial adventures: is there an original sin of American that hasn’t been owned up to?

JB: Yes. There is a question of how the nation state functions as a precondition for the organization of knowledge, So, again, you can have progressive multiculturalism in the nation state, feminism or queer studies within the nation state – the US or Israel, for example – and they can even become a defining characteristic of one’s democratic and progresive character. But all of these movements and academic inquiries can work to reconfirm the ideas of the nation state over against those nations, peoples, etc. that are “threats” to the national state, that are much more difficult to think about

What is really upsetting, and one of the reasons we are upset afresh and anew, all of the time, is because many of these forms of argumentation are not about establishing what is true, and they are not really about trying to understand reality, in any sense. So for instance, the people who actually question whether Obama was born in Hawaii (even though the evidence is undeniable) don’t actually care whether or not it’s true. In making the claim, what they do is appeal to a felt sense of illegitimacy. They’re basically saying, “How could this man be the President of the United States? He’s not a legitimate American.”

We could ask whether the point of the charge is actually to cast doubt or to produce an aura of illegitimacy around the person, even if there are no good grounds for doing so. They care less about whether or not the grounds are there, than they care about the effect of the charge itself. Similarly, when the Koret Foundation says that Jewish Voice for Peace, by supporting the showing of the Rachel Corrie story in the Jewish Film Festival, indulges anti-Semitism, when they make this claim, how would you find out the truth of that? They know they can’t establish the truth. They don’t care whether the truth is established. But by casting aspersion in that way, they delegitimize Jewish Voice for Peace as an organization that can represent Jewish opinion. It’s the delegitimating effect of the aspersion itself which is really what’s going on.

The same with David Horowitz, and even Stanley Fish. If you look at the way they operate, they claim that certain kinds of political speech are not appropriate in the classroom, or that certain kinds of political speech should be rigorously separated from academic inquiry. This is certainly a ridiculous claim. What if you’re actually writing a book about why it is that Zionism is illegitimate? What if that’s your normative thesis? What if you’re writing a book about the dispossession of the Palestinian people, and the unjustness of that, and you have a strong normative component of your book? That’s an acceptable thing to say and do.

ML: This is similar to what happened earlier this year to UC Santa Barbara Professor William Robinson, himself Jewish, when he circulated an email comparing the Gaza and Warsaw Ghettos in a class on globalization and conflict and the ADL and other conservative Jewish groups put a huge amount of pressure on the University Administration to punish him.

JB: Yes, absolutely. This violates some of the most basic principles guiding academic inquiry. In fact, a publisher could reject your book, for example, if it did not have a strong normative claim. But, if, suddenly, taking a political view is un-academic, than indeed whole dimensions of political science, political theory, sociology, critical theory, any of a number of academic inquiries that depends on strong normative claims – philosophy itself – would be undermined. it doesn’t even make sense as an academic argument. But it obviously casts aspersion on those who take certain strong political views – not all political views – and makes them seem illegitimate.

ML: Let’s not just focus on Israel. There’s gay and lesbian studies, ethnic studies – the whole Horowitz hit list. Is there a link between the assault on so-called “radical” disciplines and the larger wasting away of academic freedom in this country?

JB: I think it’s a really good question and can work both ways. I think there are people who can defend women’s studies, gay and lesbian studies, African-American studies, but they get more worried when it becomes a question of post-colonial studies or scholarship critical of Israel. So I actually see there to be fissures in the liberal defense of progressive academic inquiry. They have a limit that they won’t go beyond. I’m not sure they have a justification for it. It’s not thought through. It’s kind of strange.

ML: Is it because in so many ways we remain a colonial country, with unresolved issues concerning the native peoples we mostly exterminated? Forget about our current imperial adventures: is there an original sin of American that hasn’t been owned up to?

JB: Yes. There is a question of how the nation state functions as a precondi- tion for the organization of knowledge, So, again, you can have progressive multiculturalism in the nation state, feminism or queer studies within the nation state – the US or Israel, for example – and they can even become a defining characteristic of one’s democratic and progressive character. But all of these movements and academic inquiries can work to reconfirm the ideas of the nation state over against those nations, peoples, etc. that are “threats” to the national state, that are much more difficult to think about and reconcile with.

ML: Recent editorials in the New York Times and Washington Post about the settlements didn’t even mention the word “illegal.” They praiseed Obama for calling on Israel to stop construction now and in the future, but insisted that the Arabs now have to come forward with “major concessions,” since Netanyahu is going to have to be forced to undertake this incredible sacrifice of, essentially, stopping his government from violating international law. If there wasn’t such complete ignorance of the reality on the ground, then they couldn’t get away with that sort of argument, bereft of historical or political context or honesty.

JB: I do think there’s enormous ignorance. That is true. We cannot get the history of land seizure. we cannot get the history of colonialization, or even try to make the argument that the colonization of Palestine is part of the history of colonialism, or that settlements are the continuation of forcible colonization. Even if you wanted to take a less politically powerful claim – for example, to say that these settlements are illegal because they go against UN resolutions or international law – to claim that they are illegal, or are manifestly illegal, is considered an incendiary act. That’s really stunning. We cannot even name illegality, as such, without being accused of somehow waging war.

This is profoundly embedded in American reporting and journalism. I think we’ve seen some cracks in that. Major figures like Jimmy Carter have made a difference, although he was immediately suspected of nascent anti- Semitism by saying what he said. Moving that kind of an understanding into the dominant media seems exceedingly difficult. I suppose that it’s one of the ongoing tasks of intellectuals of our time to try and figure out how to tell these stories and make these arguments in ways that can actually puncture what seems to be a hegemonic lock on the presentation of Israel for the American public.

ML: Would you say, aside from the political and moral “problems” of Zionism and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, that they also raise philosophical and anthropological questions that in many ways are unique, and epistemologically productive?

JB: Yes. That’s absolutely true. And it’s a problem of language as well. In so many areas. To cite one, I decided actively to write on these topics in response to the question of state violence when I realized that most of the people I knew who were Jewish felt that they needed to vacate their Jewishness because they couldn’t stand Israeli politics. I asked myself “Why is it that we think that to be Jewish is to be pro- Israel,” and “What is this language anyway?” I actually don’t even like the language of “pro-Israel” and “anti-Israel.” I think there are ways of actually criticizing what has come to be a kind of camp formation.

That is really important, because if the land of Israel (whether it is called Israel) becomes a binational state, or if it takes on a different political character, it will probably better for all of the people in those lands. So we’re not “against” these people, and “for” these other people. What are we really “for”? A more just political formation, one that would allow for equality at the level of citizenship. Religion may be extremely important, but I don’t think it should be a prerequisite for citizenship, and certainly not there.

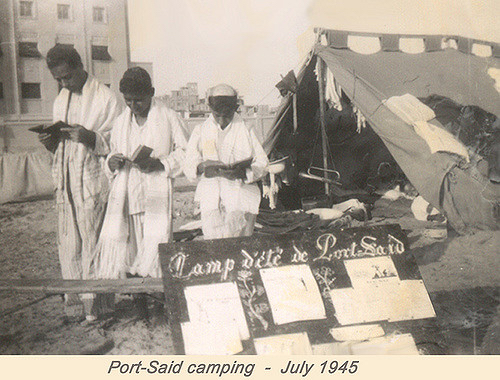

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit