For my birthday last week, I received three T-shirts featuring Walter Benjamin. It’s hard to imagine a better example of “long tail” marketing. I was delighted. But one of them made me uneasy. Playing off the now-ubiquitous religious slogan, it asks, “What would Benjamin do?” The truth, though, is that few thinkers have been less invested in getting things done.

Yes, reading and writing are technically activities. But they served Benjamin as an alternative to traditional work, something to do instead of doing something. And even when he did stand up from his desk and go outside, he preferred to spend his time wandering without any particular destination in mind.

By the time he was accumulating material for his vast Passagenwerk, theorizing this form of existential drift had become a central preoccupation. Benjamin was particularly interested in its relationship with consumer society. By excavating the history of modern life in his studies of Paris in the years between Waterloo and Sedan, he opened up intellectual space for a special type of action, the sort that takes pleasure in not realizing its ostensible purpose. He found his preferred term for those who devoted themselves to such aimlessness, flâneur, in nineteenth-century journalists’ attempt to make sense of metropolitan experience and in the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, who did his best to turn that experience into a self-conscious aesthetic program.

As the English name for the Passagenwerk, “Arcades Project”, suggests, Benjamin regarded the development of spaces neither wholly public nor private as a crucial step in the rise of flânerie. The biggest reason, simply, was that such spaces made it possible for crowds to move about without being subject to the elements. But a close reading of his work also suggests that he was struggling to discern a link between their hybrid character and the peculiar combination of detachment and fascination that defined the flâneur’s attitude towards his — or her, theoretically — surroundings.

the development of spaces neither wholly public nor private as a crucial step in the rise of flânerie. The biggest reason, simply, was that such spaces made it possible for crowds to move about without being subject to the elements. But a close reading of his work also suggests that he was struggling to discern a link between their hybrid character and the peculiar combination of detachment and fascination that defined the flâneur’s attitude towards his — or her, theoretically — surroundings.

It was as if navigating spaces where one did not fully belong, because they belonged to someone else, generated the frisson necessary to sustain the interest of those who wandered the city for no reason other than their own pleasure. In other words, the fact that the Parisian arcades were essentially an early form of shopping mall was of crucial importance for Benjamin’s reflections on modern life, one that must not be forgotten in trying to repurpose his work for our own times.

Would Benjamin’s dedication to Marxism would have been sufficient for him to take issue with the enormous mall recently constructed in his hometown of Berlin? It is tempting to think so. Yet the evidence throughout his writings, from the fragments of his never-completed Passagenwerk to the many short feuilleton pieces he published before being forced to flee Hitler’s Germany, suggests that he would have welcomed the opportunity to reflect on the tenacious fantasy of a place cordoned off from the city proper.

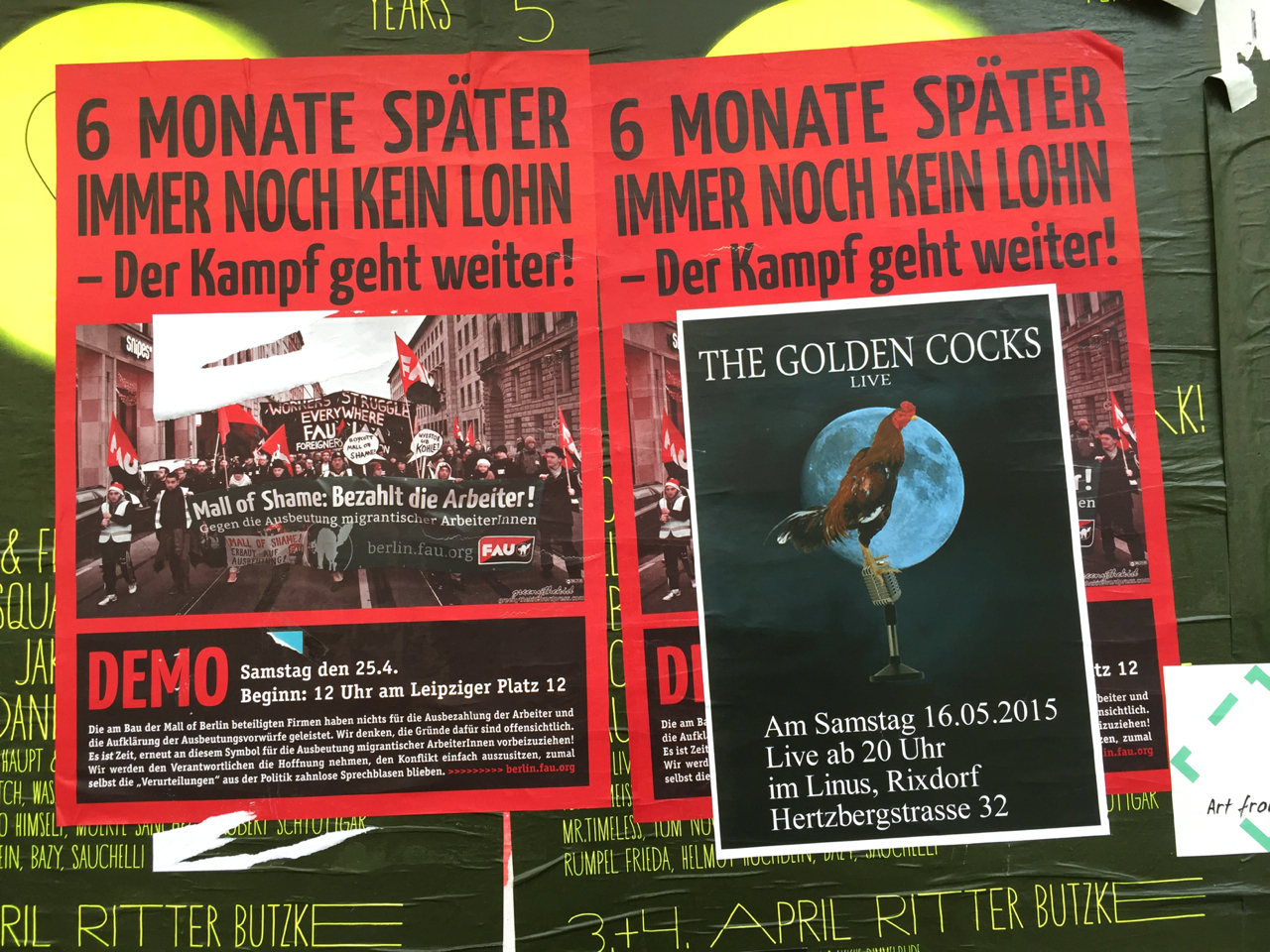

Although Benjamin would surely have noticed the protesters outside declaring it a “Mall of Shame” for the contractors’ failure to compensate the immigrant laborers who actually built it and perhaps mused on their plight — the time he spent with Bertolt Brecht would have helped in that regard — there’s a good chance that he would have found the structure’s failure to win over consumers every bit as moving. Because, whatever its limitations or those of the shopping mall more generally, it still functions as a place where people can pass their time with no particular place to go.

What would Walter Benjamin have done, if faced with this conflict? Probably not much of anything. But it’s a safe bet that he would have called into question the idea that culture is only what happens in the absence of shopping. indeed, you could argue that the main point of his work, when considered as a whole, is that the pursuit of culture will be a self-deluding enterprise until it acknowledges that everything we do already has a cultural dimension.

Actually, considering the fact that Benjamin was drawn to the decaying remnants of post-Napoleonic arcades that he found in between-the-wars Paris, he would have been intrigued by the prospect of the Mall of Berlin turning out to be a failure and, if he had the opportunity, to explore its depressing half-emptiness long after the initial excitement of its construction had worn off. That wouldn’t do much for the immigrants who are still looking for a paycheck, but it would at least make it possible to consider the complex’s shame from a new perspective.

Protest photograph courtesy of Joel Schalit. Mall of Berlin photograph courtesy of Alf Igel. Published under a Creative Commons license.