It’s a landmark achievement. UKIP won 3.8 million votes, and secured one parliamentary seat, as well as control of Thanet Council. Nigel Farage lost his bid for South Thanet, as Mark Reckless lost his seat, leaving Tory defector Douglas Carswell to hold on in Clacton. This right-of-centre party has broken into the mainstream after two decades on the margins. UKIP now has more than the hectoring voice of Lord Pearson to speak for it.

For a fleeting moment, it looked as if Nigel Farage would live up to his promise to resign if he lost. It wasn’t unimaginable, as he gave up the leadership once before, back in 2009, when the British National Party was the flavour of the month. The success of the BNP reached its peak in that moment. Nick Griffin used the party as a springboard to take his seat in the European Parliament and quickly became detached from the grassroots of his party.

One would hope Nigel Farage would suffer the same fate as Griffin. The national executive of UKIP rejected his offer of resignation and the everyman was reinstated as leader without a minute of notice. The Daily Express journalist and UKIP MEP Patrick O’Flynn has come out with excoriating words in the Times against Farage. It was predictable from the outset. The sharks were already circling when Farage pledged to resign in the event of defeat in South Thanet.

By 2010 it was clear Nick Griffin was not going to pose a white nationalist challenge to the centre-ground. It was around this time that Farage regained control of his party. Four years on, Griffin was bankrupt, living in exile from the European Parliament and his party of 19 years. He had suppressed a leadership contest and ultimately lost as his party self-destructed. Naturally, the white nationalist came out in support of UKIP. He told his Twitter followers to “hold your nose” and vote for Farage in order to take a dirty stick to the Conservatives.

There are important differences between UKIP and many other right-wing alternatives. Unlike the BNP, UKIP represents a coalition of libertarians, traditionalist conservatives and nationalists. This populist formation cuts across the middle-class and reaches into the ‘white’ working-class for support. By contrast, the BNP held onto a primarily working-class base. The leadership included figures, such as John Tyndall and Nick Griffin, who were lower middle-class. But it was never quite the same beast as the UK Independence Party.

The parties are essentially different animals, but they do hold attributes in common. Much of the BNP came out of the National Front, a neo-fascist organisation, which attempted to conceal its racial agenda to ‘purify’ the land, going after Blacks, Asians and Jews. This is not the case with UKIP, which is primarily concerned with forcing the Conservatives rightwards. It’s unlikely, given its composition that the UKIP phenomenon will disappear overnight. There are no serious contenders on the alternative right.

The BNP began to fray as soon as the English Defence League emerged and grew into a separate organism. The far-right is fragmented to the extent that it has regressed into street-level hooligan activities. The Britain Firsters are the latest incarnation of this, except they know how to use social media to promote their ends. Not insignificantly, Jim Dowson, the man behind Britain First, has openly attributed the rise of UKIP to a general rightward shift in the discourse. The party model has not served the far-right well.

The question, whether or not UKIP can make further gains, depends on a few key factors: 1) how Farage handles the leadership contest, 2) the result and how it shifts the party’s trajectory, 3) whether a new far-right party emerges; 4) what happens in 2017 and 5) what happens to the Labour Party. The EU referendum offers the possibility of British withdrawal, but the result could either kill or boost the anti-EU movement. A withdrawal could serve to deprive UKIP of its raison d’être and create an opening for the Conservative Party to reclaim lost support.

Likewise, if the British people voted ‘yes’, UKIP would lose its claim to represent a ‘silent majority’, but the far-right could well be hardened. It’s also plausible, if UKIP decapitates itself, that the party will run itself into the ground in the absence of a personality at the reins. There is plenty of time for a new far-right grouping to take shape, but it would take a long time for the strength of the BNP to be recreated. Perhaps most importantly, the Labour Party may well take another right turn, in a bid to outmatch the Tories, and this could turn off even more working-class voters.

It shouldn’t be forgotten that UKIP did very well in many Labour strongholds. In Doncaster Ed Miliband won, but UKIP came second place. If the official social democratic party abandons all progressive opposition to austerity, finance capital and the EU, the results could be disastrous. UKIP can fall back on racial populism to bind the working-class to itself by virtue of whiteness. Racial consciousness has been a powerful rival to class consciousness in Europe for a very long time. We may well be heading towards a situation where the only opposition to liberal capitalism will be nationalist populism.

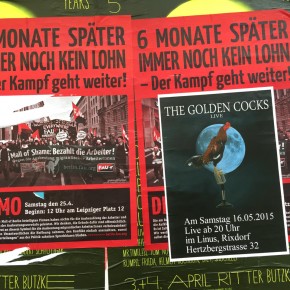

Photographs courtesy of the European Parliament and Funk Dooby. Published under a Creative Commons license.