There were many issues excluded from the elections. The major issues were social and domestic policy: austerity, immigration, the NHS. Foreign policy was almost completely absent. Yet the issues were presented as if they do reside in a vacuum. The context surrounding UKIP’s rise was lost to 24 hour news. The same can be said for the SNP and the Greens. The difference is that the rise of UKIP fits into the overall shifts of politics in recent years. It’s not just that the Conservatives forged a right-wing opening in 2010. The prevailing current has been rightwards since 2008.

At first it was the global financial crisis. The right-wing press slated New Labour for the bank bailouts. Tory politicians quickly began to complain of ‘overspending’. This is despite George Osborne’s approval of the spending plans. The Right saw the deficit as a chance to continue its bid to tear down the welfare state. The Cameron government did not just succeed in its first term due to the lack of opposition. The right-wing narrative was maintained for five years. The momentum was fed by certain events: the most important may be the summer riots of 2011.

The riots burst out of Tottenham following the shooting of Mark Duggan by police officers. It all began as a demonstration, which due to high emotions became violent. In the days afterwards young people took to the streets across London, and in northern cities like Manchester, smashing in shop windows, setting fire to buildings and looting retailers. It was not a riot in the politicised sense of the term. It was shopping with violence, the ultimate extension of commercialism, the underbelly of our consumer culture.

Of course, the ultimate crime was that the rioters were taking consumer goods without paying for them. Much of the right-wing opposition was entirely hypocritical. It was not really about the destruction of a public space. The symptomatic scene was Michael Gove posturing on Newsnight. He claimed to stand for ‘order’ amid the fires of discord. It might’ve held more traction had Gove not argued that the Iraq war was justified by economic growth. If only the yobs had created jobs, then they could have killed thousands.

White Rage

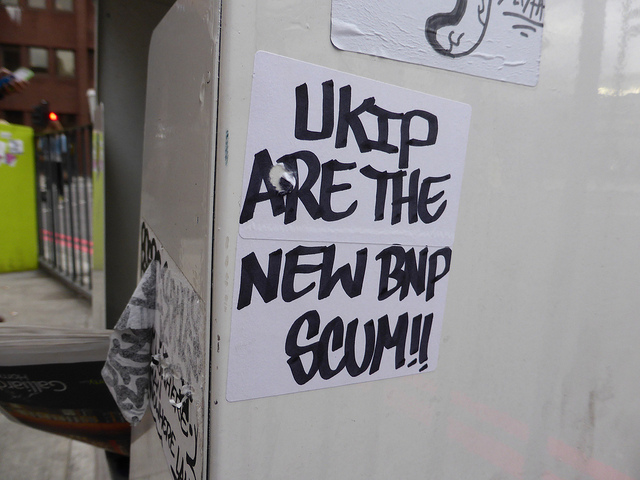

The far-right made its bid to seize upon the riots. At the street level, the BNP and EDL began to organise counter-forces to patrol neighbourhoods. Fortunately, by this point, the BNP was already poised for its terminal decline. The EDL had come into its own as a street-level force, but it could not capitalise on the riots. It could not reach beyond its anti-Muslim focus. Especially, as the rioters did not represent any singular ethnic or religious group. The EDL could not hide behind the signifiers of ‘Muslims’ and ‘Islam’ for a racialised threat.

Consequently, the riots would not provide any sustainable boost. The presence of thugs looking to engage in grass-roots intimidation was short-lived. It wasn’t like the 2001 riots in Oldham and Bradford, which burst out of the white enclaves and Asian neighbourhoods of northern cities. The potential for inter-communal bloodletting was not so high in this case. The racial animosity was between the black working-class and the overwhelmingly white police force of London. But this was the only political aspect.

The rioters represented London’s diversity – with whites and people of colour united – first in anger against the police, then against the shops and everything in between. The middle-classes were outraged at the sight of such destruction. Hordes of middle class people turned out with broomsticks to clean up the damage. Social media was littered with comments to the effect that “whites cleaning up after blacks”. The fact that neither the clean-up crews, nor the riotous youth, were homogenous did not matter.

The Cultural Front

The new divisions were drawn along cultural lines, as David Starkey argued on Newsnight. Starkey raised Enoch Powell’s Rivers of Blood speech in a new formulation. It wasn’t inter-communal violence, he emphasised, nor was it racial – it was cultural. Starkey claimed that the “whites had turned black”. This was while the Right was scrambling for a narrative. It blamed the riots on everything from benefits and family breakdown to video game violence and football. It didn’t have to be coherent; it just needed to hold together.

It fit into the consensus, shaped by the press, on benefits: specifically that the poor are scum, entitled, pampered and out-of-control. There was soon talk of claimants being stripped of social housing, if they had partaken in the riots. Soon the mayor’s office was seeking new powers for the police, who sought water cannons to deal with unruly scum. It looked as though the party of ‘order’ would triumph. In general the summer of 2011 would fuel the increasingly Victorian attitudes towards the under-class.

The old antagonism, the most English of all, class would deepen. The race problem, the muffled voice of the black working-class, and the brute force of the police, would be unresolved. Yet it was apparent that the Conservatives were not harsh enough for some people. The riots fit another picture, one in which national decline came down to multiculturalism, immigration, social deprivation and ‘soft-touch’ domestic policy. The rioters were just chavs ‘turned black’.

The new populism

During the mad days of August, Nigel Farage was calling for the army to be deployed. He was not alone by any measure. “Should we try to understand this?” Gavin Esler asked Kelvin MacKenzie. The former editor of The Sun was succinct: “No, I don’t think we should”. MacKenzie was quick to call for the troops to be sent out. He called for the rioters to be shot, but only with rubber bullets he added hastily. In this rhetoric, ‘justice’ means punishment and vengeance.

Nigel Farage framed the root problems as underachievement, welfare dependency and drug use. He turned the Left’s narrative on its head. The social ills were simply immanent to the lower orders. At least Farage was cautious of the use of water cannons and plastic bullets. UKIP’s preferred response was symmetrical to the root problems: the withdrawal of the social safety-net and easy recourse to emergency measures. The UKIP vision for Britain was a small state which will be capable of keeping the ‘feral’ masses in their place.

It wouldn’t be until late 2013 that UKIP would emerge as a right-wing alternative. The party’s leader Farage had already become a media darling. He appeared on BBC Question Time 14 times between 2009 and 2013. This is more than any other politician. UKIP expanded its presence in the European Parliament in 2014. By far its greatest victory was in securing its first seats in the House of Commons (only one of which remains). This coalition of libertarians and nationalists has serious appeal to traditional Tory voters.

The riots did not undermine the austerity dogma. Instead the populist Right regrouped, but not around ‘order’. As Richard Seymour pointed out in 2013, the paranoia of UKIP sees the insecurity, social deprivation, and supposed racial ambiguity of the working-class, as symptoms of Britain’s absorption into the EU. It’s just further proof of the rot at the centre of British public life. The sight of hooded youth ransacking shops, stopping only to check whether the shoes fit first, hardened the right-wing consensus.

The 2011 riots may be a catalytic moment in the pace of the rightward shift. The Conservatives can’t satisfy public opinion with its toughest benefit cuts. Nor can David Cameron convince the public that he will limit immigration. In the wake of the austerity measures, and just before we face even deeper cuts, the discourse has opened up to the first cross-class populist movement in British history.

Photographs courtesy of Joel Schalit