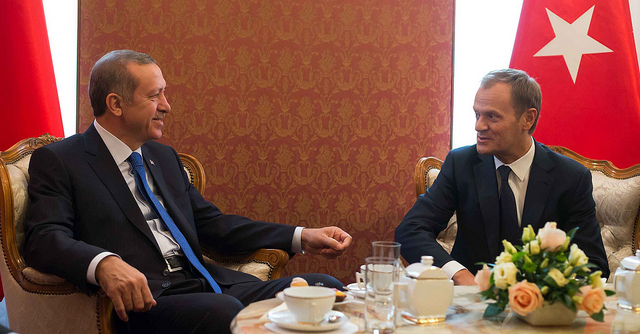

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been savage in his criticisms of the EU. “The European Union’s court, the European Court of Justice, my esteemed brothers,” Erdoğan exclaimed after an ECJ ruling in March allowing employers to ban the headscarf, “have started a Crusade against the Crescent.”

“Europe is swiftly rolling back to the days before World War II,” he added.

Since then, Erdoğan has also called the Dutch and German governments “Nazis,” “Nazi remnants,” and “fascists,” following their cancellation of referendum rallies, blasted Europe as a “sick man” (a twist on pejoratives about the Ottomans), and most recently, commented that German companies “are more intelligent, more visionary, and more prudent than its politicians.”

These gestures may seem like they’re aimed at the EU’s Turkish diaspora, especially in light of the constitutional referendum in April, but it is also important to remember that Erdoğan’s support is not without qualifications in Europe.

It is more likely that these insults are meant for a domestic nationalist audience that sees Erdoğan as a hero, and potentially even a leader of the global Muslim ummah, in the spirit of the Ottoman Empire.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been promoting Islamic nationalism for several years, in reaction to the Gezi Park protests, and the remarkable success of Kurdish and minority-led parties in the June 2015 election. One of his main strategies has been to challenge the country’s near century-long policy of secularism.

The strategy appears to be working, with Erdoğan successfully appealing to voters to expand his powers. The result is a divided country which is increasingly coming to resemble a Sunni Iran, albeit with the continued support of the United States and the European Union, and, more recently, Russia.

Erdoğan’s insults play an important role in nurturing this majoritarian consciousness. Indeed, the AKP leader takes advantage of rising Islamophobia in Europe to support his own belief that not only are Islam and Europe fundamentally separate but that Turkey belongs to the former rather than the latter.

As a religious conservative, this allows Erdoğan to reject the Western-influenced republicanism of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and most aspects of parliamentary democracy as European, and therefore un-Islamic and anti-Turkish.

It is also important to remember that Turkey’s president has been cultivating nostalgia for the glory and splendor of the Ottoman Empire in order to frame his authoritarianism.

The Ottomans were the last Sunni Islamic caliphate, and as a result had a specific duty to represent and protect the world’s Muslims. Erdoğan can’t benefit from its legacy without some Muslim internationalism, like his negative comments on recent Israeli-Palestinian clashes in Jerusalem.

Erdoğan’s anti-Western polemics are most likely to work inside of the country, rather than with Turkish communities abroad, though he is gaining ground with Turkish voters in Germany, a majority of whom supported his bid for expanded presidential powers in April’s referendum.

While it is true that Erdoğan is growing his influence in clerical networks to gain more influence internationally, this presupposes that the mosque is the center of community life abroad that Islamists insist it is at home, which is not consistently the case in the Turkish diaspora.

In a series of interviews with German Turks conducted by the New York Times following the referendum, the majority of those the American newspaper spoke to gave the impression that the Turkish president was making life more difficult for them than anything else.

Expressing a sense of alienation from other Europeans for being identified as Turkish, to being reluctant to openly criticize Erdoğan out of fear of retaliation, a pronounced sense of anxiety emerges in the piece about being dislocated – culturally, as expats, as well as politically, in Turkey.

‘Insult’ nationalism may work, as a political strategy, to rally voters. But it also appears to fracture the Turkish ummah.

Though German Turks may feel compelled to pay lip service to Erdoğan’s leadership, the Times article makes clear that he’s also sowing deep feelings of shame and embarrassment over Turkey.

For a president who appeals to a typically nationalist sense of victimization to create community, such reactions, particularly among expats, make perfect sense. Their broader political experience, as dual citizens, encourages greater thoughtfulness about what it means to be loyal, albeit where.

Photographs courtesy of Kancelaria Premiera and PASCAL.VAN. Published under a Creative Commons license.